Fair warning, this is not what most riders would think of as a "normal" motorcycle story. Sure, there’s a motorcycle in it, but that motorcycle is almost an afterthought.

That it was an afterthought is very likely why it still exists today, and why I find myself taking on perhaps the most challenging story I have ever worked to tell.

Not many motorcyclists will look at a mid-1960s Honda 305 twin and have the first thought that springs to mind be "power." But if that motorcycle is Robert Pirsig's 1966 Honda CB77 Super Hawk, they might well be looking at the most powerful motorcycle that ever existed. This Super Hawk's power, though, is not the kind you're probably thinking about.

The unexpected bestseller; not about motorcycle maintenance

When the author and philosopher Robert Pirsig's book "Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" was published in 1974, it had already been rejected by 121 publishers, and the editor who worked with him at William Morrow publishers — James Landis — gently counseled his new author not to expect that he'd ever see anything more than his $3,000 advance. From our vantage point in 2024, that narrative seems implausibly ironic — Zen is the best-selling book on philosophy that has ever been published, with over six million copies having been printed, and with the work translated into 27 languages.

In the author's note to the 25th anniversary edition, Pirsig writes that his book "should in no way be associated with that great body of factual information relating to orthodox Zen Buddhist practice. It's not very factual on motorcycles, either."

To recap, "Zen and The Art of Motorcycle Maintenance" is not about Zen. Or motorcycles.

Check.

Take it from a certified writing nerd — as a work of literature, Zen is a work of extraordinary scope. Pirsig constructs a literary matrix out of a system of independent narrative threads and his philosophical dialogues, then uses each to develop the other.

Pirsig has four narrative roads that he travels down.

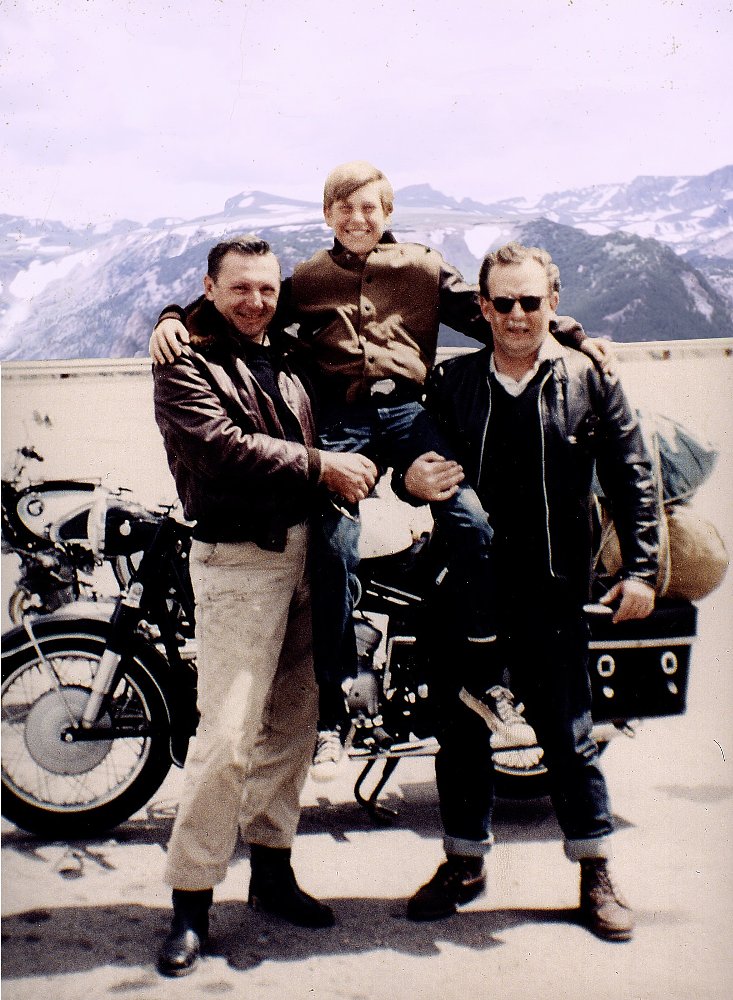

The first is the surface tale of Pirsig's motorcycle trip with his son and their friends, John and Sylvia Sutherland. There is the road, with its sun, rain, and dust. The natural landscape. And there is the motorcycle, which must be taken care of, so it will get one home.

The second story is that of the author's past — only remembered in fragments because of a prior psychiatric hospitalization, during which he was treated with a far cruder and more disruptive version of electroconvulsive therapy than that which is presently used. One effect of the therapy is a break with one's previous personality and memories — the trip is a backtrack, a retracing of steps, designed to help Pirsig rediscover the person he was before his treatment.

The third story is adjacent to the second — the development of Pirsig's personal beliefs and philosophy while both a student and a professor. Zen's subtitle, "An Inquiry into Values," comes to the forefront here. Pirsig evaluates and either discards or integrates every school of thought in the histories of both Western and Eastern philosophy, finding at least a half dozen ways of taking an analytical blade to ways of looking at the world of human existence, thought, and effort. Pirsig, after years of writing, thought, and classroom discussions — an experience that drove many of his students, and arguably himself, to at least the threshold of insanity — settled on the notion of "Quality" as the axis around which all of human thought and endeavor revolved.

With these four stories to interleave — Pirsig used a system of index cards while he wrote to organize chunks of narrative — Zen manages to relate the discussion of every major school of philosophical thought into illustrations from the narratives. The result is an incredibly information-dense work that is structured in the way that a software engineer would order it, like a large database. If the goal of the novel is to create a world, Pirsig takes a run at portraying the world we're all living in, trying to explain why we do what we do, and what the point of it might be.

To the reader, it can be heavy going.

I reread Zen preparing for this story. As a guy who sometimes grabs a snooze in the evening, Pirsig's book kept me up, kept me pushing farther into the text, and left my brain smoking when I'd hit my ingest limit for the day.

You are not obliged to give my opinion of the work any credence.

When the book was first released in 1974, George Steiner, the literary critic for The New Yorker magazine, compared Zen to Melville's "Moby Dick."

(Mic drop.)

A Honda Super Hawk goes to the Smithsonian

In December of 2019, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History put out a press release describing how Robert Pirsig's widow, Wendy, had reached out to the museum to offer them Robert's personal effects, including the Super Hawk he had ridden on the famous trip, along with his tools, his riding gear, and other artifacts. Pirsig is one of the influences on my own craft, and the notion of being able to encounter these objects directly was something I found very exciting.

We agreed we'd do this sometime in the springtime … of 2020.

That did not work out as planned.

The Smithsonian was one of the first institutions in the federal city to go into full lockdown in response to COVID, and the non-public areas of the building — the conservation work areas — were the last to come out. I'd occasionally send a "Ping!" message to Paul, and I'd get back a "Not yet, but soon!"

This pattern repeated.

Until the morning of February 28, 2024, when I stood in front of the museum on a miserably rainy morning waiting for opening time. At 10 a.m. sharp, the doors were opened and I got to come in out of the rain.

In the lobby, I was met by a nice lady named Laura Duff from the museum's public relations team. Laura escorted me to a staff elevator that took us down into the conservation shops and labs. Once out of the elevator, the environment took on a completely anonymous government building feel — the walls were all concrete block painted beige, there were no windows, and the floor was concrete slab — clearly used for moving larger, heavier items. One could have been in any military base or any government lab anywhere in the world, and it would have felt exactly the same.

We walked through a stainless steel swinging door, and there it was.

Dr. Paul was there too — we pumped hands in greeting — although I have to confess to having been extremely distracted.

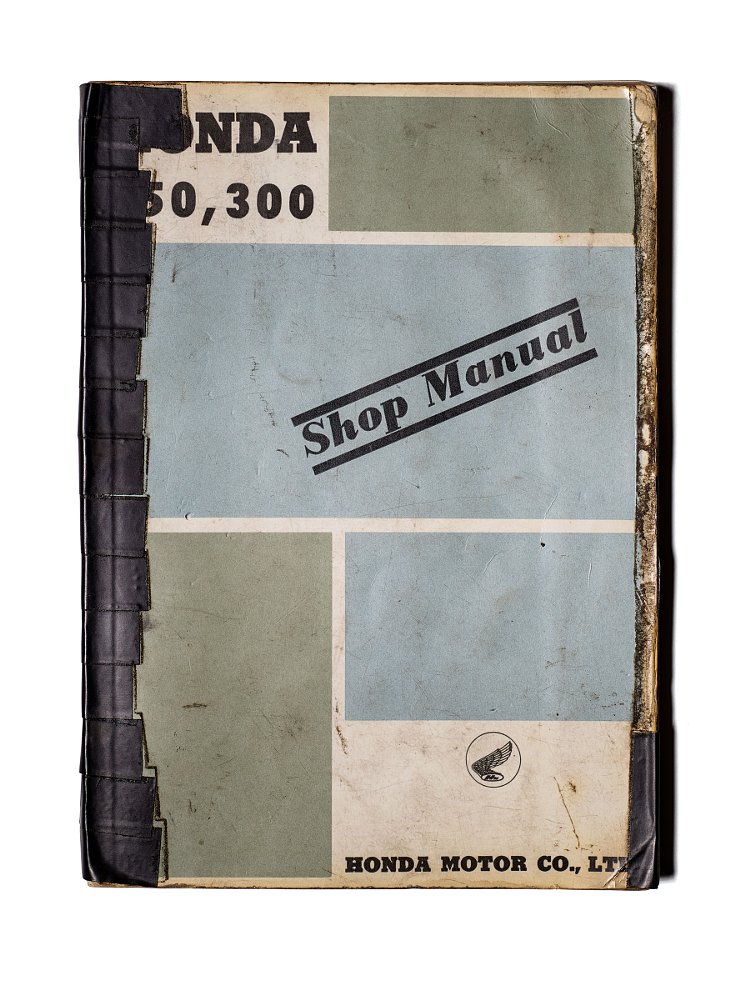

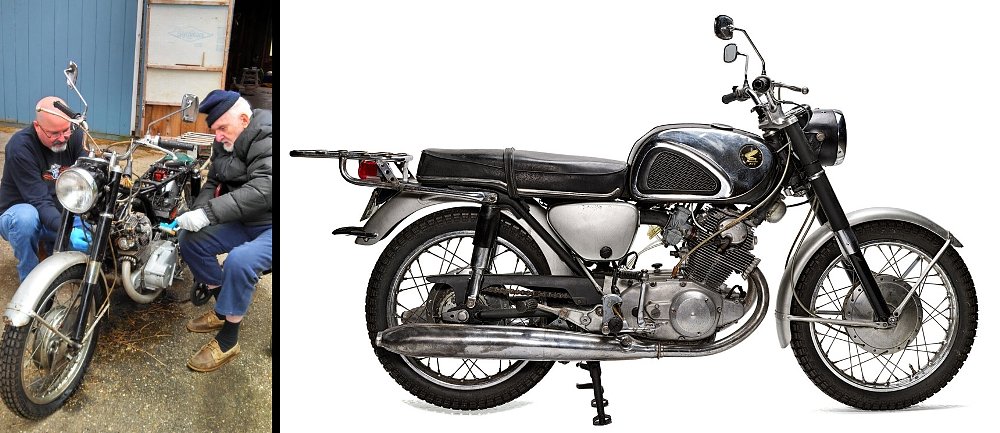

Pirsig's 1966 Honda CB77 Super Hawk has a 305 cc air-cooled, parallel-twin engine with a single overhead cam. The Super Hawk is almost incomprehensibly tiny when viewed in the context of modern motorcycles — 350 pounds of machine, with a three-inch-wide rear tire, a 30-inch seat height, and making 28 horsepower on its best day.

To the eyes of a modern rider, the Super Hawk seems almost toylike.

To the eyes of Robert Pirsig, it looked like the most cutting-edge performance motorcycle available.

The guy whose friends referred to him as Bob had really wanted to learn to fly, but his previous psychological treatment and hospitalization made him unable to obtain an FAA medical flight certificate. As the next best thing, he had originally bought himself a Honda Sport 90. Coming from the 90, with its eight horsepower and pressed-steel frame, the CB77 was a rocket ship from outer space — 28 horsepower, a tubular steel frame which used the engine as a stressed member, and a top speed of nearly 105 miles per hour. With these specs, the Super Hawk was running in the same frame as 500 cc Triumphs, for a fraction of the cost, and at likely far higher levels of reliability.

Sitting there in the conservation lab, the Super Hawk's appearance was challenging to reconcile with the intellectual and spatial adventures I knew it had helped catalyze. Pictures taken during the trip that makes up the core of Zen show a nearly new motorcycle. Its black and silver painted parts were shiny, and the chrome tank sides, exhaust, and headlamp trim were all proudly bright. The CB77 gave up nothing in appearance to European sporting motorcycles like the BMW R60/2 ridden by Pirsig's travelling companions on the trip. This CB, though, clearly showed the fingerprints of having lived a long and much used and much beloved motorcycle's life. The bike's now dulled paint showed many scuffs and scratches, and signs of having been touched up by hand to address normal moto wear and tear and an occasional gravity related mishap. The fenders sported their fair share of dents and undents, and looked well worn. The odometer displays over 33,000 original miles.

As a student of Pirsig's book, I looked for some evidence of Bob's travelling gear and roadside-repairs, as related in Zen, that were no longer in evidence on the motorcycle sitting before us. Zen relates how the Super Hawk's chainguard had been nearly destroyed when a master link failure allowed the drive chain to tear the thin metal. A fortunate encounter with a talented roadside welder — repair of such thin alloy is challenging, at best — had allowed the original chainguard to get them home from their 5,700-mile ride. The chainguard repair, which had cost them a single dollar, was no longer in evidence. An OEM part must have replaced it after the famous trip.

Pirsig was, at heart, a talented engineer and fabricator — a solver of problems — and the motorcycle landscape of 1968 lacked many sources and solutions modern riders utterly take for granted. In an environment where touring gear wasn't readily available, Pirsig made the things he needed. Bob was a committed map enthusiast, and 40 years before the commercial availability of GPS, he had fabricated a tank-top map holder, an ingenious device that allowed a roughly eight-by-10 slice of a paper map to be securely held and displayed on the top of the CB's tank. Pirsig had also adapted a set of Buco "Bubble Bags" — a common accessory for the Harley-Davidsons of that period — to allow the CB to carry the gear needed for the long trip he'd planned. Sadly, the bag frames, bags, and map holder were no longer in place on the CB.

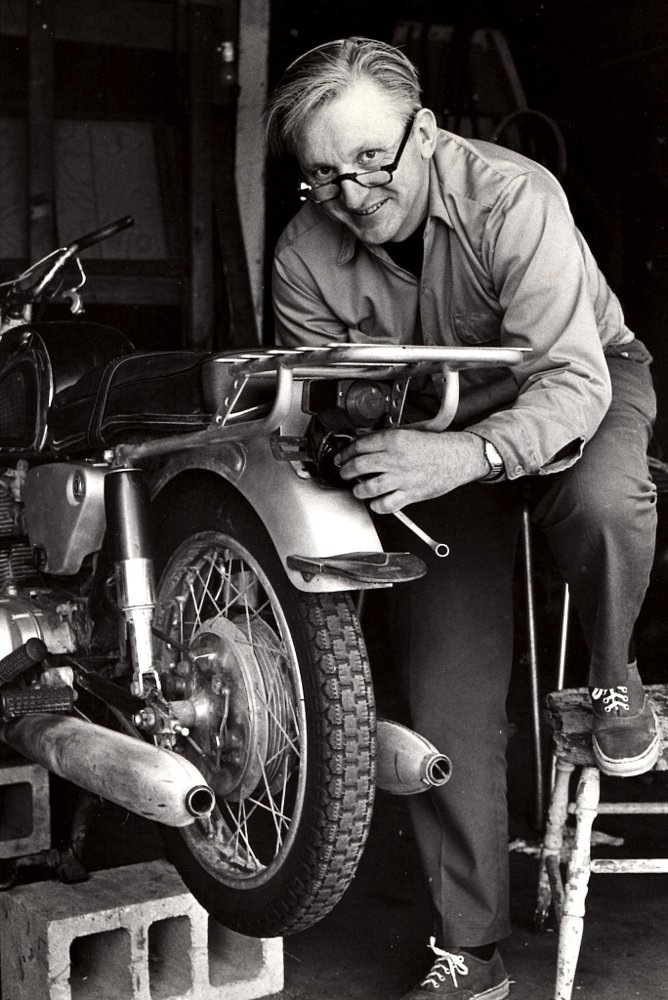

Dr. Paul described to me the process of obtaining the motorcycle after his communication with Wendy Pirsig. In his last years, an ailing Bob Pirsig and a friend who was a local motorcycle mechanic had completely stripped the Super Hawk and done a thorough mechanical restoration. Anything that was worn and no longer serviceable was replaced while the time-earned patina of the machine was left untouched. Upon his arrival at the Pirsig homestead in Maine, Dr. Paul had found the CB safely parked in the home's garage with a Battery Tender hooked up and in working order. He described the bike as being in "ready to ride condition."

I playfully inquired how he knew that the Super Hawk was ready to ride.

The good doctor smiled. I'm pretty sure he didn't exactly answer my question. I know how I would have made such a determination.

Part of the Smithsonian team that prepared the Pirsig artifacts for exhibition is Dawn Wallace, the museum's Head Objects Conservator, who worked both with the motorcycle and some of the other artifacts that make up the Pirsig exhibit. Dawn related how the motorcycle had been readied for display. The battery was removed and engine drained of all fluids, and then the engine was "fogged," a common practice in aircraft and marine conservation, to ensure its internals were protected from seizure and corrosion. She related how her team had been meticulous in cleaning and documenting the bike as an important historical artifact, while being careful to avoid doing anything that might be classified as restoration. The Super Hawk's patterns of wear, small injuries, and cosmetic defects really were its story.

That process was not without its own surprises. Dr. Paul had discovered that at some point the bottom of the Super Hawk's engine cases were welded up to close a hole. Pirsig's tendencies toward what we now call adventure riding had clearly not been something that was restricted to the famous ride.

Dawn also showed me the complete OEM toolkit that had apparently been in its proper place under the motorcycle's seat. I had a 1970s vintage Honda. To see one of those toolkits with the vinyl bag still intact at more than 50 years old is almost as miraculous as the Shroud of Turin.

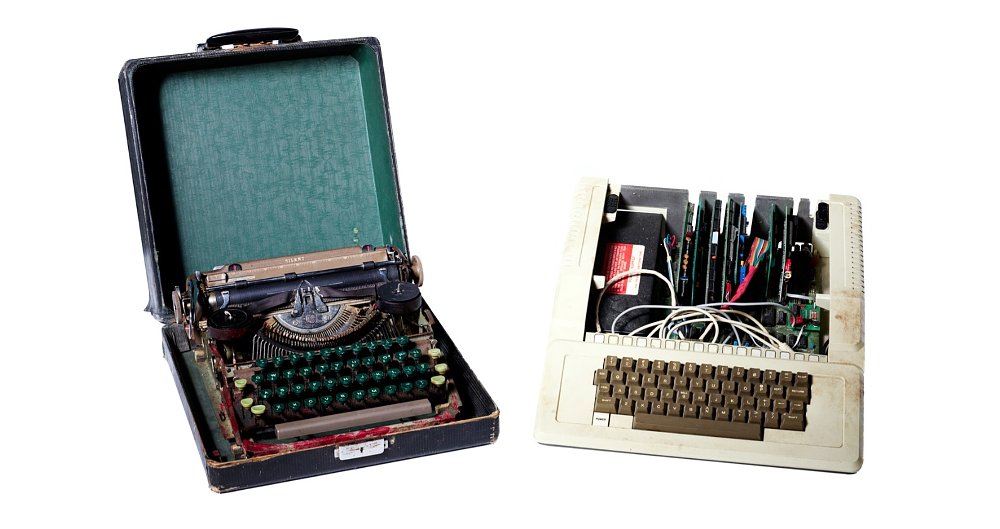

There were other artifacts from the Pirsig bequest in that lab, and the team walked me though them. Bob's bomber-style jacket and open face helmet, both aged and fragile. The portable manual typewriter on which Zen had been written. An Apple II computer on which Pirsig had written his second novel, "Lila."

Dr. Paul indicated I should come closer to the Apple II. He lifted the lid to let us see into the computer's main board.

"I've seen a bunch of these things over the years," he said. "I've never seen one with seven of the available expansion card slots filled."

It seems Mr. Bob had been a bit of a computer guy, as well.

Dr. Paul related that Pirsig had done some custom programming to modify a commercially available word processing program to better suit his needs. He was so convinced his version was better that he tried to buy the rights to the program, but the publishers didn't see it that way, and declined the deal.

And as potentially overstimulating as the notion of writer/philosopher as computer software engineer may be to me, my attention just kept getting pulled back to the tiny, dull grey and black motorcycle sitting in front of me.

Motorcycles like this have such incredible stories to tell that I can literally hear them speaking to me. The enormity of their experience creates echoes across time that one can hear if one is open to the experience.

One of Giacomo Agostini's MV Agusta race bikes spoke to me in this way. In its presence, one could hear its four-cylinder, high-rpm howl and the roar of the spectating thousands.

Robert Pirsig's Super Hawk spoke to me, too.

It was a lighter, softer song — the sound of a twin-cylinder Honda wound most of the way to redline, and staying there for days upon days at a time — a mantra for figuring out the entire world and how it worked.

Visit the exhibit

If you'd like to experience Robert Pirsig's motorcycle yourself, along with the other personal items described above, they are now on public display at Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History, 1300 Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, D.C., 20560. The exhibit, titled "Zen and the Open Road," is part of the museum's Transportation Gallery on the first floor. There is no charge for admission.

Sincere thanks to Dr. Paul Johnston for his willingness to share his expertise and enthusiasm.

Membership

Membership