Dale Walksler was one of the icons of the antique and historic motorcycle world. Born in Illinois and drawn to motorcycling in his teens, Dale brought a degree of energy and enthusiasm to anything and everything motorcycle that had never been previously seen. By his early 20s, Dale had already owned and run two successful motorcycle businesses.

Dale's dad, Bernie, took out a mortgage on the family home to make sure Dale got his shot at success when the opportunity arose to purchase a Harley-Davidson dealership and move it to Mt. Vernon, Illinois. Dale made the most of that opportunity. Running what became Dale's Harley-Davidson, Walksler was the youngest dealer Harley-Davidson had ever engaged and, despite Mount Vernon's rural location, he built the dealership into one of the highest volume locations in Harley's network by following the apparently unknown "golden rule" of motorcycle dealerships: Treat every customer exactly as you would want to be treated.

Good customer practices were just the beginning, though. Dale had a perfectly balanced sense of self-promotion — there are stories of him taking a bear as part of a down payment on a bike — and he was the pilot on dealership-sponsored drag racing, hillclimb, and TT racers. Over his lifetime, Dale competed in the Motorcycle Cannonball coast-to-coast runs for historic motorcycles, Bonneville land-speed record attempts, and multiple 24-hour endurance runs. The first infant iteration of what would become the Wheels Through Time Museum began as a small building behind the dealership, where antique cars — mostly Cadillacs and Packards (and some old motorcycles) — were kept to help drive more traffic into the dealership and sell more bikes.

The collection, though, started to take on a life of its own.

Dale poured some of that boundless energy into picking, and doing the swap meets, and cutting deals. More and more time was spent in the shop during the second and sometimes the third shift, rebuilding and restoring all of that history. It was really the history that put the light in the eyes of the riders Dale talked to, and it was the history that became the light in Dale's eyes, too. All of a sudden, selling motorcycles became somehow less important than telling their stories.

Coincidentally, Harley-Davidson had some ideas of its own about how dealerships should be run, what the showrooms ought to look like, how the product ought to be floorplanned, and how much square footage needed to be dedicated to Genuine MotorClothes and lifestyle accessories. Dale's Harley-Davidson might have been selling more bikes than anybody, but it wasn't doing any of those things. In short, the guy that Dealer News Magazine had named Dealer of the Year/Best Marketer four years in a row was being told he didn't know how to market.

Dale felt like it was maybe time to cash out and do something more to his liking — and the Wheels Through Time Museum burst into the light.

The word got out. Even Hollywood came sniffing around. Dale ended up on TV, in shows like "American Restoration," "American Pickers," and eventually his own show, "What’s in The Barn?" Visitors to Wheels Through Time started coming from everywhere. I went myself, many years back when a family vacation took us past the bridge over the creek that leads to the museum. That day's schedule got adjusted, and we had a great visit.

The first article I published on Rolling Physics Problem was about that visit. And I got a personal thank you note about the piece from Dale. It was just how he rolled. He wanted to high-five anybody and everybody that he could help make feel good.

One day, I saw in the news that Dale had been suffering from cancer and had passed away. I felt like I'd been gut-punched, all of the air knocked out of my lungs.

Meeting the son, virtually

During the summer of 2020, many people spent a lot of time binging YouTube. I may have been one of those people. During that enforced couch-exile, I saw a video called "Why Would Someone Build This?" The subject of the video was a homemade motorcycle powered by a Harley-Davidson single originally used in a 1913 model. The motorcycle was funky, it was weird, but the amount and quality of the work that went into all the custom-fabricated parts was staggering. The presenter on that video was natural, engaging. It was like this guy and his weird bike were right in my living room. I was instantly and totally hooked.

That guy was Matt Walksler, Dale's son.

I watched more than a few of the videos that Matt called "The Drive for History." There were motorcycles one would expect — a Crocker Big Twin, Hendersons, and Aces — along with some of the homebuilts and oddballs that make up the Wheels Through Time collection. All of Matt's presentations were an amalgam of engineering and understanding of the bike's significance. All were done with no script in one shot, recorded straight through with no obvious edits. Most of these motorcycle tours ended up with either the bike being started and run, or Matt riding the bike, either inside the museum or outside on the grounds.

One video featured a Harley-Davidson 350 single factory racer that had been campaigned by legendary racer Joe Petrali. Matt's comfort with the material was palpable. He seemed to know everything about Petrali's astoundingly versatile and successful racing and engineering dual careers, and he was equally well informed on the internal details that distinguished Petrali's factory racer from production engines.

Matt seemed as comfortable in the role as someone slipping into a leather jacket they'd been wearing for 20 years.

Meeting the son, in Maggie Valley

Maggie Valley, North Carolina, where Wheels Through Time is located, lies in a steep-walled mountain valley. U.S. Route 19, which the locals call Soco Road, runs along the narrow bottom with the valley's walls rising to either side, 4,000 feet straight up into the clouds. That topography seems to funnel weather coming across the Blue Ridge Mountains into a point, right over the museum, which may be why it seems that every time I go to Wheels Through Time, it rains.

I'm really not fond of motorcycle trips where there's a schedule, but the weather reports showed some extreme rainfall forecast for the evening when I was planning to arrive and continuing for the entire day of my visit. The message was if I didn't arrive by about 6 p.m. that I'd best be prepared to swim for it, so I spent the day on my old BMW touring bike with an eye on my trip computer and jamming the Interstates for more than 500 miles as the weather window slammed deterministically shut.

I turned onto U.S. 19 about 60 miles west of Asheville, just as the rainfall started.

I was the first person through the door in the morning, feeling more than a little self-conscious wearing the moto-journalist's stereotypical Aerostich in an environment where moto-fashion runs more towards a 1920s vintage wool racing jersey with Indian lettering on the front. After shedding my foul-weather gear and taking more than a little good-natured and entirely deserved ribbing from the museum staff in the process, I found myself standing right next to the 1935 CAC factory dirt racer — the Joe Petrali bike I'd seen in the video — which had been placed in the place of honor right inside the door.

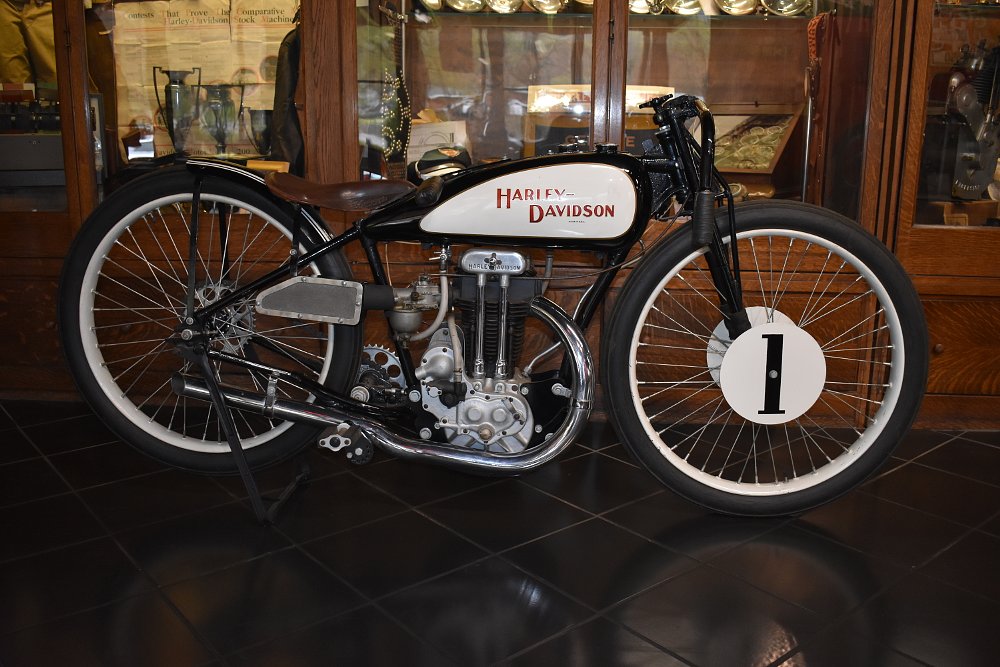

The CAC was an AMA Class A racer — a 350 cc, single-cylinder machine. If you have a mental picture that lights up in your brain when someone says the word "motorcycle" — two wheels, finned engine, a place to hold on, and nothing more — then Petrali's CAC is the embodiment in metal of that image. The elegance and economy of the bike's design is unrivaled. It has a single-loop, rigid-rear frame, a padded leather saddle, teardrop two-tone tank, and a girder-style sprung fork with drop bars that were typical of the period. The bike is direct drive, as are most early board-track and flat-track racers, with no clutch and no brakes. The bike is as beautiful as it is fast.

As stunning as it is, the CAC wasn't why I was here. Matt Walksler was. I introduced myself to the staff, and one of them set about locating Matt.

A minute later, we were shaking hands and making small talk. Matt shared with me that he had bought the first new motorcycle of his adult life — a new Harley-Davidson Pan America — and how much of a change it was from the bikes he was most acquainted with and how much fun he was having with it when the long hours in the shop and museum allowed time to get out and ride it just for the joy of it. He led me upstairs through the display space to some comfortable leather wing chairs in the museum's private office space off the mezzanine.

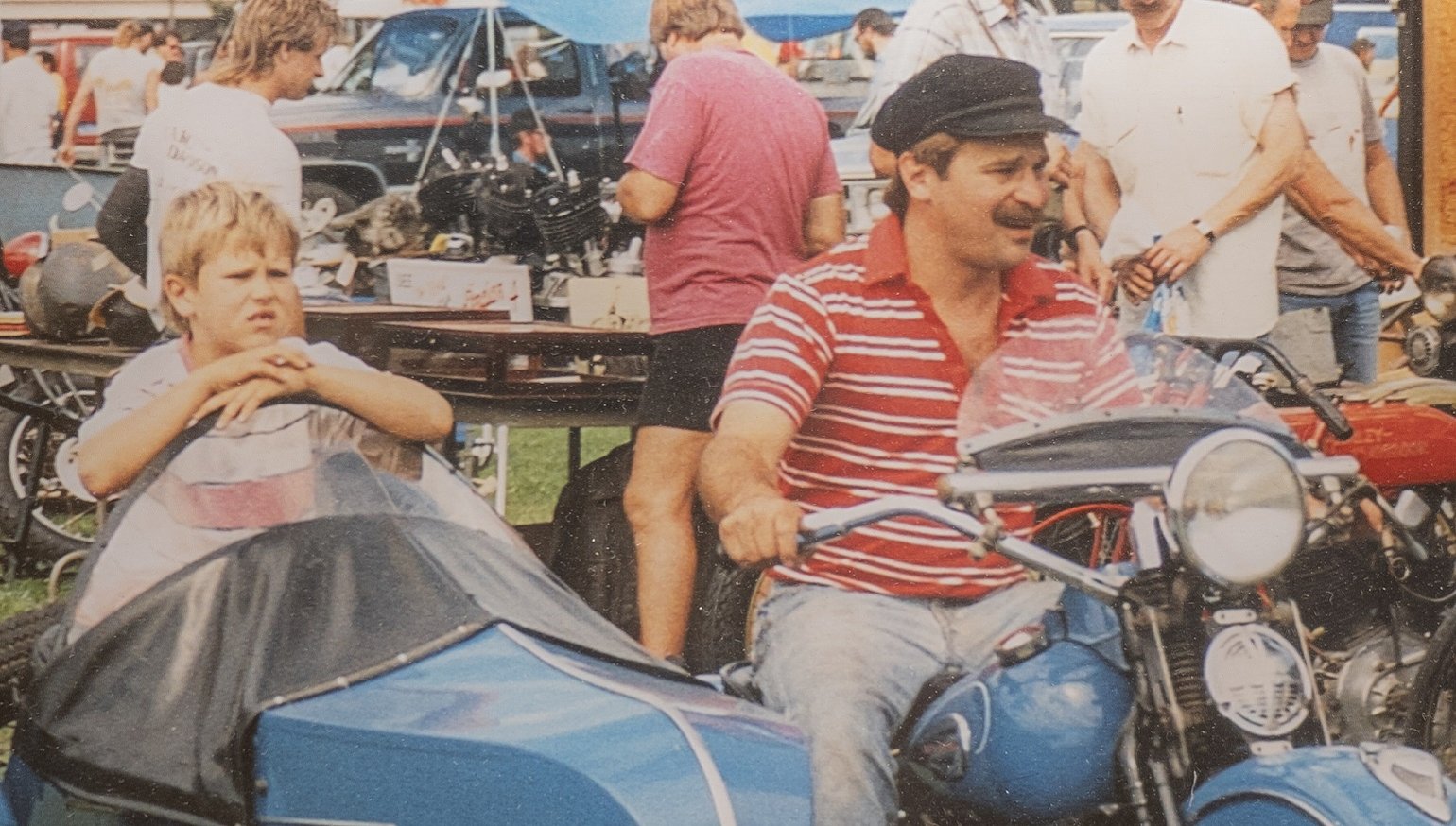

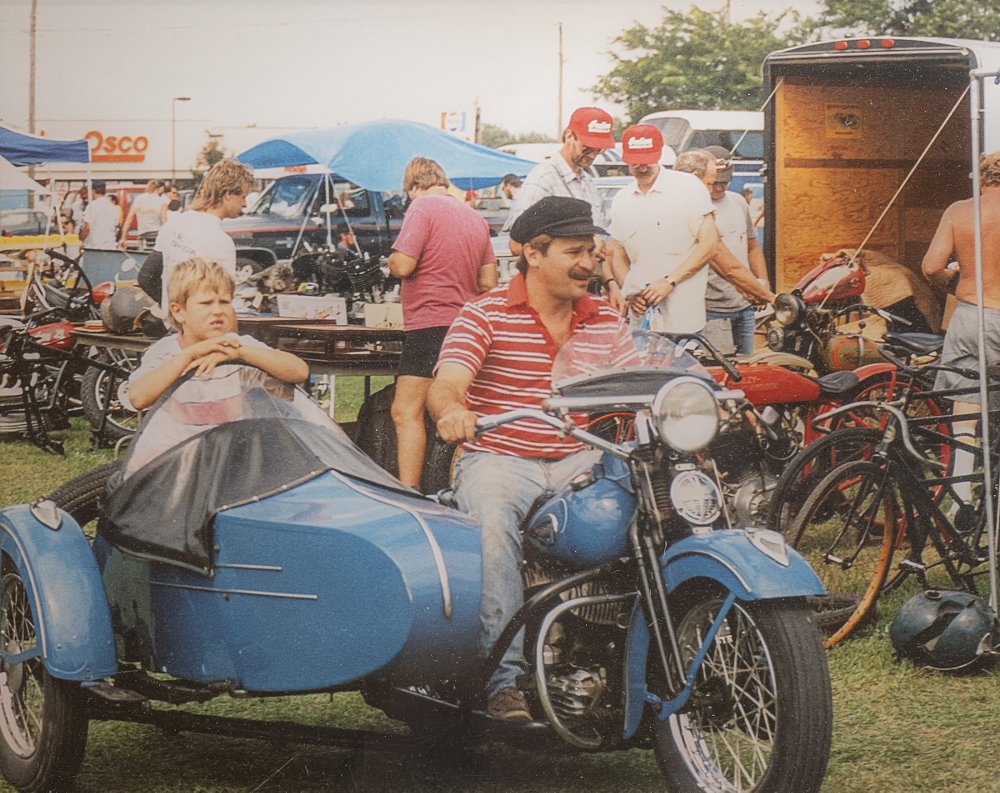

"My first memory was sitting on my dad's Panhead… His hand was on my hand and he was showing me how the throttle worked." Matt made the universal gesture for WFO that each of us knows instinctively.

Matt's earliest memories were mostly mental pictures of sitting on the tanks of his father's Harley-Davidsons. Matt's first memory of riding a motorcycle was from when he was 5 or 6 years old, as a passenger in Dale's 1940s Flathead factory sidecar outfit. Time spent with his dad was "all bikes, all the time. It was life-changing stuff, man."

Perhaps like many of you, I grew up in a household where Dad's rules started with "No motorcycles while you live under my roof." So let's pause for a second to absorb Matt's upbringing. And it wasn't like Dale was the only motorcycle role model that Matt had available. When the AMA Pro Flat Track tour came through Illinois, guys like Jay Springsteen and Scotty Parker would stop by for social calls. Matt described one scene where Dale was teaching Springer, one of the most gifted flat-track racers of the modern era, how to ride an antique flat-tracker with a foot-operated clutch. The scene had resulted in, at least initially, way more laughter than forward motion.

"Growing up around that scene was just amazing," Matt said.

Being a kid in Dale's household wasn't all fun and games, though. Hanging around the family dealership as a kid, Matt was put to work doing dirty jobs like running the blasting cabinet when he was only 12 or 13 years old. Later, Dale got in the habit of turning abused or derelict trade-ins over to Matt with a simple instruction: "If you can fix it, you can ride it."

With that kind of motivation, one can understand how Matt might have gotten pretty skilled at fixing things. Getting good, though, also had a downside. "I'd fix it. I'd ride it. I'd come in one day and he'd have sold it. Then I'd get another one and we'd start all over again."

As much as a life filled with motorcycles and motorcycling legends would seem to determine a fixed path, though, it didn't guarantee that Matt Walksler would end up where he is today.

As a young man, Matt was a successful athlete playing soccer on the youth and collegiate levels, and went to university and obtained a degree in economics. Fresh out of college at 22, though, like so many others, Matt had no real idea what he wanted to do for a living, and found himself back at Wheels Through Time. The museum property, which had formerly been a campground, has a gatehouse cabin that sits on the bridge that allows visitors to cross the creek and enter the grounds. Matt moved into the gatehouse and found himself gaining the type of antique motorcycle experience really not available anywhere else.

"There isn't a classroom like this anywhere else in the world," he said. "I had a 40-yard commute. Work would start at 7:30. The museum would open at 10 and close at 5. The second shift in the restoration shop would start at 5:30 and we'd work until 2 or 3 a.m. most days. A 100-hour work week was the norm. We had a shop full of projects and I was jumpin' full on into that."

It wasn't a traditional classroom, though, with Dale methodically teaching Matt what he knew. Wheels Through Time was more of an immersion environment where folks who had the curiosity could learn, rather than be taught.

"Somebody of his proficiency, passion, and ability — he wasn’t going to teach it to you. But he sure was the best guy in the world to shadow," Matt said. "You want to know how to lace a wheel… I'd watch him and then I'd be jumpin' in."

At one point, Matt obtained a rare early Harley-Davidson Panhead motor, holed himself up in the shop, and completely rebuilt it. Dale took a look at the work Matt had done and that light bulb — probably a six-volt one — came on. "OK, so the kid can do this."

A bigger, brighter light bulb came on for Matt, though. It was a genuine moment of enlightenment. "This is definitely what I want to do for the rest of my life… this shit is cool," he recalled.

And then came racing

Every motorcycle journey has a fork in the road. Matt Walksler had looked at both routes away from the fork, and then went down the one where the old motorcycles were. Wheels Through Time has one of the most complete collections of American competition machines from the early 1900s to around 1930: board-trackers, hill-climbers, flat-trackers, and outlaw roadracers. Bikes that were as fast in 1929 as what we still had to work with in the early 1970s. Those impossibly muscular and incredibly fast motorcycles really spoke to Matt, and attracted both his interest and mechanical attention.

Matt was hooked on these classic period racers — closely coupled, rigid chassis, drivelines with direct drives without clutches or transmissions, large-diameter wheels and absolutely no brakes. If the engine was running, the back tire was spinning. What else do you need? What Matt needed, it turned out, was not just to appreciate these bikes, but to actually ride one in anger. The racing bug had bit, and left quite a mark.

So Matt Walksler went racing. And apart from showing up with a good motorcycle, he was a good pilot, and at the end of the event, Matt and his bike ended up on the podium, placing second in his first-ever outing.

All motorcycle racers have thought the same, very dangerous thought that Matt did then. "Hey, if I can find just a little bit more in it, I can win!" When he got back to Maggie Valley, the racer's engine went back on the bench.

When Dale discovered that the shop had now become the "racing development department," he and Matt had some sort of little moment. It's hard to say what really bugged the old man about the proceedings. It might have been the 179 or so motorcycles in the collection that hadn't been restored yet, or that somebody might find racing more compelling than curating, or the escalation of risk and parental concern that goes along with competition, or even some weird gumbo of all three with some other stuff mixed in. But suffice it to say that, for a while anyway, it became something that couldn't be agreed upon. And it kind of busted up the band.

Matt Walksler took a break from Wheels Through Time and "found a nice place about five miles up the road, with my own shop, and did my own thing for a while. Built bikes for me and for other people." Time tends to get away from you. That break turned into a couple of years.

At one point, a longtime friend of the family passed away. The memorial service was at Wheels. Memorial services do help to crystallize one's thinking around the fundamental fact that none of us last forever. That day provided father and son with a chance to talk, and at least a chance to get past what couldn't be agreed upon. Matt went back to working at the museum.

It wasn't too long after that Dale took ill and had to start cutting back his time at the museum. Soon, staffers were taking bikes or engines over to Dale's house to help keep him involved. He'd call in multiple times a day for progress on projects in the shop.

And it wasn't too long after that the man that seemed as fast as an XR on the straight at the Springfield Mile and as indestructible as Milwaukee iron was inexplicably gone. I know how bad it felt for me. For the Wheels Through Time crew, it had to have felt at least a million times worse. Still, they had Matt. Dale and Matt had made arrangements for the transition, and everyone on the team supported the idea that Matt would lead them and Wheels Through Time going forward.

When the pandemic hit, the museum — renamed Dale's Wheels Through Time — took a blow like thousands of other businesses. Admissions and the revenue that came with it went to zero overnight. Matt decided to take the museum directly to the people who could no longer come to Maggie Valley. YouTube became a virtual front door and Matt's "Drive For History" videos not only brought the museum a new, larger audience, but also helped to replace some of the revenue needed to keep the institution afloat. Those videos also helped to introduce Matt Walksler to the museum's fans and gave those fans a way to directly communicate what Dale had meant to them, and how moved they were to see Matt moving forward with the incredible work his father had started.

A new host at Wheels Through Time

Despite the deluge outside, Wheels Through Time still had plenty of visitors other than me that day. Watching Matt working the floor at Wheels is an object lesson in moto hospitality. Every visitor who wants to talk gets the chance, and there's lots of back and forth about how far the visitors have come and how their ride in was. Matt and the members of his team are always ready to provide more detail about a favorite bike on display or to demonstrate the starting rituals on these antique machines and make a little oil smoke and some serious and thunderous noises.

My personal favorite is a specially prepared competition model Henderson Four. Henderson didn't find a great deal of success racing but had hired one of the board-track hotshoes of the day by the name of Maldwyn Jones. He was to undertake a 24-hour endurance run. The idea was to stay at sustained speed for all 24 hours on the two-mile board track at Cincinnati and get into the record books. Unlike modern endurance attempts, Maldwyn didn't have co-pilots. He was planning to spend all 24 hours in the saddle himself.

During the overnight period, one of the support team moved a lamp that was lighting the track, thinking it would help, but then everything went pear-shaped. Maldwyn ended up missing that corner and did some impromptu free-form customizing of the Henderson, which put paid to the record attempt.

Dale Walksler had located and obtained what was left of the bike in 1993 and had it restored to endurance-worthy condition. The bike subsequently completed several coast-to-coast runs and a recreation of Maldwyn's original endurance attempt, during which the Wheels Through Time team was at least able to keep the bike running through all 24, a feat even Jones hadn't managed.

Watching Matt prime the Henderson and then start the bike by spinning the rear wheel by hand gives one an appreciation of just how far motorcycles have come. Listening to the inline-four bark on throttle coming out of what would have been a pretty sophisticated tuned header for an archaic inlet-over-exhaust motor confirms just how much in motorcycling has stayed the same.

I took advantage of the day to wander through the collection. I spent time with those early Harley and Indian racers, and with the extensive collection of American fours — Hendersons, Aces, and Indians all — and in the "teen area" shop where the early pioneer bikes and one-of-a-kinds are concentrated.

Being on the museum floor, a weird thing happens. Reality itself seems to take on a vintage sepia tone, like an old photograph. One special bike is Dale's 1903 Indian Camelback Century Racer, a bike that appears to be original and unrestored, and with which Dale used to consistently hustle and win every race for 100-year-old-plus motorcycles that he ever entered. There's a picture of him aboard that bike at what passes for 1903 speed with a grin on his face and a lit stogie in his mouth. It tells you everything you need to know.

A presence in the shop

Matt swung by and swept me back up. "Come on, let me show you the restoration shop." He took off at a trot toward the rear of the complex and I did my best to keep up.

Exiting the rear of the museum space and making a right puts one in front of another, smaller steel building. Entering through the door feels a lot like entering Aladdin's Cave of Wonders. There are rare motorcycles, frames, wheels, motors, sheet metal, carburetors, and other components as far as the eye can see. Lately, Matt has been interacting on his YouTube channel with Sean of the "Bikes and Beards" channel. Sean has been working with some older Harleys and Indians and needed some expertise and services. The relationship has proven helpful for both partners. Sean had, largely by accident, obtained an extremely rare Harley-Davidson WLDR racing motor. Matt had identified it and agreed to overhaul it. Sean, with his more than one million subscribers, had featured Matt and Wheels Through Time on his channel, and the exposure had helped to drive a 25% increase in subscribers and viewership.

Matt walked me around and showed me some other projects in the shop. The beginning of a new Knucklehead build that has the potential to end up as the 2023 annual museum raffle bike, and boxes and bins that contained another rare 1930s Harley. All of the parts — including some unobtainium, single-year-only components — were there, but the bike would need to be completely rebuilt from the frame up.

We took up a spot next to the workbench and just talked bikes for a while. While we talked, Matt pulled up a completed V-twin bottom end and absent-mindedly stuck his index fingers into the connecting rod little ends that were protruding from the cases. He moved the connecting rods in a way which had the crankshaft slowly spinning and his left and right hands going up and down in the unique H-D uneven firing order. To someone who hasn't spent their riding life in the Harley universe, it was the most effective way of making the 45-degree twin's operation instantly concrete. To Matt, though, it was muscle memory, just like breathing in and out.

I shared with Matt that even to me, it felt like Dale was here in this shop with us.

"I've thought a lot about bringing someone here to help me in the back shop, but I just haven't done it," Matt said. "This was his thing, and it was our thing. So it's a chance to continue spending some time with him. When I'm into some work that's got me thinking hard, I find myself asking, 'Would Dale have done it that way?' There's things every day that I see him doin'."

The second generation and beyond

There have been a few American families that have made motorsport into multi-generation familial traditions. Harleys and Davidsons spring immediately to mind, with Fords, Roberts, Andrettis, Unsers, and Earnharts somewhere close behind. I don't know that I can say with certainty that any of the second or third generations of those clans could stand toe to toe with their founding patriarchs.

Matt Walksler seems different, though.

Matt is directly engaging new enthusiasts, both in person and by using all that technology can provide. In a world where both internal combustion and motorcycling itself seem increasingly under threat of extinction, this approachable, affable, knowledgeable guy talking to me every night from my laptop screen gives me hope that another generation of enthusiasts will be able to appreciate all the stories and all of the engineering effort it took to get us where we are today.

For a son to take on the entire work of his father's life and somehow manage to drive that work forcefully forward in new and different ways, to make that dedication longer than one man's life, to make it span generations, the son has to be willing and able to really go hard. The good start counts for something, but eventually, you've got to do it on your own.

Early the next morning, I backtracked to Cherokee and started riding north towards home from the Blue Ridge Parkway's southern end. About 12 miles or so in, I was climbing the third major grade on the Parkway when another motorcycle exited the corner coming toward me. That bike was a brand new, black-on-black Pan America. In the fraction of a second I got to look at it before it shockwaved past me, it was clear that its long-travel suspension was topped out from acceleration and only the bike's electronic stability controls were keeping its front wheel from pawing at that morning's ice-cold sky.

"Damn," I thought. "That Harley's rider is going hard."

I know someone just like that.

Membership

Membership