Early in Jeff Nichols’ film, "The Bikeriders," the director references "The Wild One" (1953). Late in the film, he gives a nod to "Easy Rider" (1969).

Although there was only 16 years between those two movies, they established iconic “biker” images of two very different generations; the first being a post-WWII and Korean War cohort, and the second springing from Vietnam-era counterculture. Nichols’ screenplay tells the story of a Chicagoland motorcycle club caught up in that same convulsive generational change.

The film was inspired by photographer Danny Lyon’s book, also titled "The Bikeriders." Lyon hung out with a club (or gang, you choose the word) called the Outlaws from 1963 to ’67. It’s clear from the intimacy of Lyon’s environmental portraiture that he had their trust and access during that time.

"The Bikeriders" was published in 1968. He went on to have a significant career as a photojournalist and "The Bikeriders" was reprinted in 2014 by Aperture, a respected publishing house that specializes in photography. It’s still in print.

The Outlaws still exist, too, although the barely fictionalized club was renamed the Vandals for the purposes of the film. I’ve heard the Outlaws didn’t approve the use of their club’s moniker.

The motorcycle industry may not approve, either

When "The Wild One" came out in 1953, Triumph resented the fact that Marlon Brando’s character rode a Triumph Thunderbird. (They’ve since softened that position.) Since the 1980s, Harley-Davidson has carefully co-opted some “biker” imagery but it’s the exception. The rest of the motorcycle industry has worked hard to distance itself from the outlaw gang phenomenon. It would be reasonable for a site like Common Tread, which generally sees riding motorcycles as a sport or pastime, to want nothing to do with a movie in which motorcycle riders stagger out of a bar and ride off bare-headed.

I don’t endorse that behavior either, but in the general North American psyche (or movie audience) the image of a Hells Angel is usually found somewhere near the idea of “motorcycle.” And while it’s tempting for those of us in the motorcycling-as-sport camp to claim that we’re the real riders and have nothing at all in common with thugs or would-be posers, we share some roots.

Lyon shows this in his photos and expands on it in his introduction to "The Bikeriders" the book. “In the early fifties, the Chicago Outlaws Motorcycle Club was formed by bikeriders who had been meeting informally on the west side of the city. In 1958 the president of the club, who is now a motorcycle racer, tried to change the group into a competition club that would require its members to race occasionally. Opposition developed among the membership and the club split, half the riders going with Johnny Davis, a transit truck driver.” (That’s the character played by Tom Hardy in the film version.)

Somewhere on the list of things the Motorcycle Industry Council would like to forget is the fact that before their infamy, the Hells Angels promoted AMA-sanctioned events.

Even though it models reckless behavior, there’s a lot to like about the bikes and riding in "The Bikeriders." The motorcycles seem period-correct; many of the riding scenes capture a sense of the thrill, romance, and freedom that Common Tread readers no doubt share.

Did Hollywood finally make a good motorcycle movie?

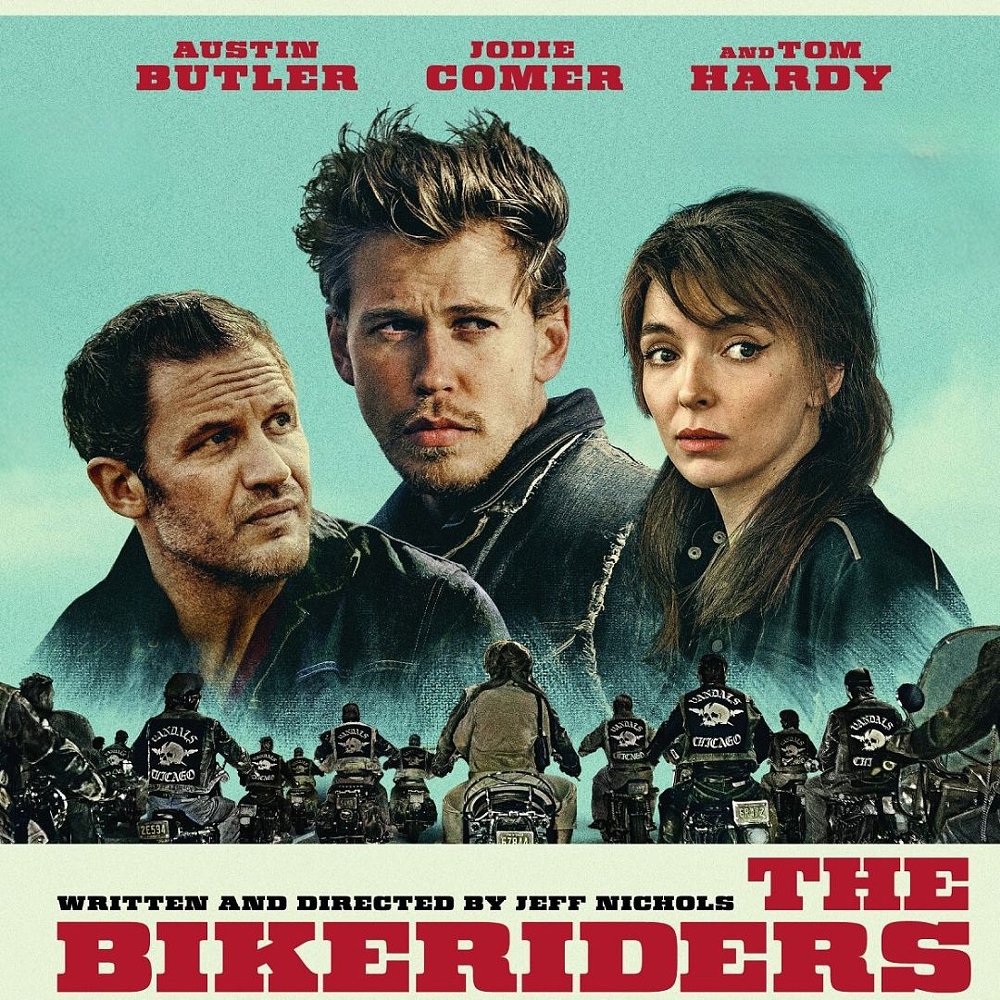

I pitched Lance a story on “The Bikeriders” before I had a chance to see it. The early buzz and impressive cast had me hoping that, finally, someone had made a really good film in which motorcycles were more than props.

Make no mistake: "The Bikeriders" aspires to be a “film,” not just a “movie.” With that in mind, I arranged to watch it with a friend, Jon Niccum; he teaches screenwriting at the University of Kansas and was a film critic for the Kansas City Star in the quaint era when local papers had local reviewers.

Despite callbacks to "The Wild One" and "Easy Rider," I doubt that "The Bikeriders" will still be part of the conversation in 50 years, the way both those films still are. It’s also not the same animal as either of those were; "The Wild One" was a straight-up studio picture aimed at a mainstream audience; "Easy Rider" was an independent, micro-budget, passion project. My friend characterized "The Bikeriders" as “a big-budget movie that aspires to be an art-house film.”

In the end, the film adaptation is very true to Lyon’s book, to the point that long stretches of dialogue are pulled virtually verbatim from transcriptions of Lyon’s tape-recorded conversations with members of the Outlaws and their wives and girlfriends. (Those transcriptions are reproduced in the book.) It’s easy to imagine Jeff Nichols coming across Danny Lyon’s book, handing it around to cool actors who love bikes, saying, “I want to turn this into a film,” and Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Norman Reedus, et al, taking one look and saying, “I’m in.”

Nichols faithfully turned Lyon’s Tri-X stills into moving pictures in a manner that’s both stylish and admirably uncompromising. The thing is, the book is an evocative group portrait and snapshot in time. It’s not a story. The book doesn’t have — or need — a plot.

To the extent that Nichols tried to inject a story in the film, it’s a conflict between an old guard of drinkers (WWII- or Korean War-vet types) inclined to settle matters with fists, and a new group of Vietnam vets, inclined to pot and heroin and guns. That’s the made-up part but it’s not enough.

Jeff Nichols was, I presume, going for a wider audience by essentially filming the movie from the perspective of Jodie Comer’s female character. Comer, as “Kathy,” is the only character who is at all three-dimensional in the film; I never understood what she saw in Austin Butler’s “Benny.”

Jon Niccum, my screenwriter/reviewer pal, came away indifferent. After taking some time to digest it, he told me, “I doubt that I’ll remember much about it a decade from now.”

Lionizing toxic masculinity

One might argue that "The Wild One" — indirectly inspired by the famous Hollister “motorcycle riot” — sensationalized the real story. Johnson Motors (Triumph importer for the western United States) urged the Motion Picture Association of America to stop production on "The Wild One" because, “To say that the story is unfair is putting it mildly, and you cannot deny that the general impression will be left with those who see the film that a motorcyclist is a drunken, irresponsible individual.”

Jeff Nichols’ take on "The Bikeriders" adds a fictional story arc, but Nichols didn’t sensationalize the gang as portrayed by Danny Lyon. The transcripts of Lyon’s conversations with the real Outlaws and the real woman behind Jodie Comer’s character capture a toxic club culture that, if anything, is underplayed in the film. In Lyon’s transcription of a conversation with the real Kathy, the real Benny comes across as a misogynistic sociopath. In the film’s most compelling scene, Kathy (Comer) is nearly gang-raped by gang members from a different chapter. That scene’s also pulled directly from Kathy’s transcript.

And yet, when it came time to title his book, Lyon chose “The Bikeriders,” not, “The Drunken Brawlers” or “The Rapists” — even though they appear to have spent as much time drinking and brawling as they did riding.

Hunter S. Thompson’s first book, “Hells Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs,” came out around the same time as "The Bikeriders." It was a huge bestseller that helped supercharge a decade of “bikesploitation” movies but it was Lyon who presented the genuine insider’s view.

As they used to say before AI deepfakes, “Pictures or it didn’t happen.” I don’t know if Lyon was “patched” but his photos make clear that he was accepted by the Outlaws — in a way that HST never was by the Angels.

There are only a few pages in "The Bikeriders" that are devoted to Lyon’s personal feelings about motorcycles and the people who ride them, but he felt that all riders had something in common. “If anything guided this work beyond the facts of the worlds presented,” he wrote, “it is what I believe is the spirit of the bikeriders: the spirit of the hand that twists open the throttle on the crackling engines of the big bikes and rides them on a racetrack or through traffic or, on occasion, into oblivion.”

Quite a few motorcyclists will like Nichols’ film adaptation of the book — not because they aspire to be like the characters in the movie, but because the motorcycles themselves are cool, if the riders are not. In the end, maybe the best thing about it is that it will popularize the book, still in print, which is excellent and a much more valuable document than Hunter S. Thompson’s apocryphal and self-aggrandizing “Hells Angels.”

Membership

Membership