As many as 40 students, mostly young engineers, from the Rochester Institute of Technology have contributed brain power to an electric motorcycle that will race at the famed Pikes Peak International Hill Climb, which begns June 30.

RIT has had a motorcycle EV Team for several years, racing against a handful of other university teams in the eMotoRacing "Varsity Challenge," which is held in conjunction with AHRMA’s annual visit to New Jersey Motorsports Park in July. This year, RIT students wanted a bigger challenge, and they got it when they secured a coveted entry in the upcoming Pikes Peak International Hill Climb.

The race is held on 12.42 miles of winding mountain road, beginning at the 9,390 feet and climbing through 150-plus turns to the summit at 14,110 feet. It’s one of America’s iconic motorsports events, having been held almost continually since 1916. Motorcycles were a part of it at the very beginning, though it was an autos-only race most years until the mid-1950s. A few years ago, after a couple of motorcycle fatalities, the race organizers threatened to return to a cars-only format, but compromised by reducing the number of motorcycle entries and improving rookie orientation.

For as long as motorcycles are allowed to race there, Pikes Peak will remain the closest thing the United States has to the Isle of Man TT — a fast, flat-out race on a closed public road, with no room for error. Like the TT, it’s a time trial; competitors launch one at a time and race against the clock.

For most of its history, the course was a gravel road, and it favored racers from dirt-track backgrounds. But beginning in 2002, the city of Colorado Springs began paving it. It’s been fully paved since 2012, but the event’s technical rules limit it to motorcycles with a handlebar, as opposed to clip-ons, so it doesn’t quite look like a road race. Some of the best prepared teams field big ADV bikes, and the current course record was set in 2017 by Chris Fillmore on a KTM Super Duke 1290. That may change because Michael Dunlop — yes, that Michael Dunlop, of Isle of Man fame — will be racing a BMW S 1000 R this year.

For now, Pikes Peak still feels a bit like Supermoto on steroids, but on the face of it, this unique race is well suited to electric vehicles. The nature of the course, with so many climbing acceleration zones, favors torque over horsepower. The short duration limits demand on batteries. And when internal combustion engines are gasping for breath at the top of the mountain, electric motors are humming.

Back in 2013, Carlin Dunne rode a Lightning to overall victory, beating all the internal-combustion bikes. And the current outright course record is held by an EV: the Volkswagen I.D.R.

The RIT entry, starring the Duke

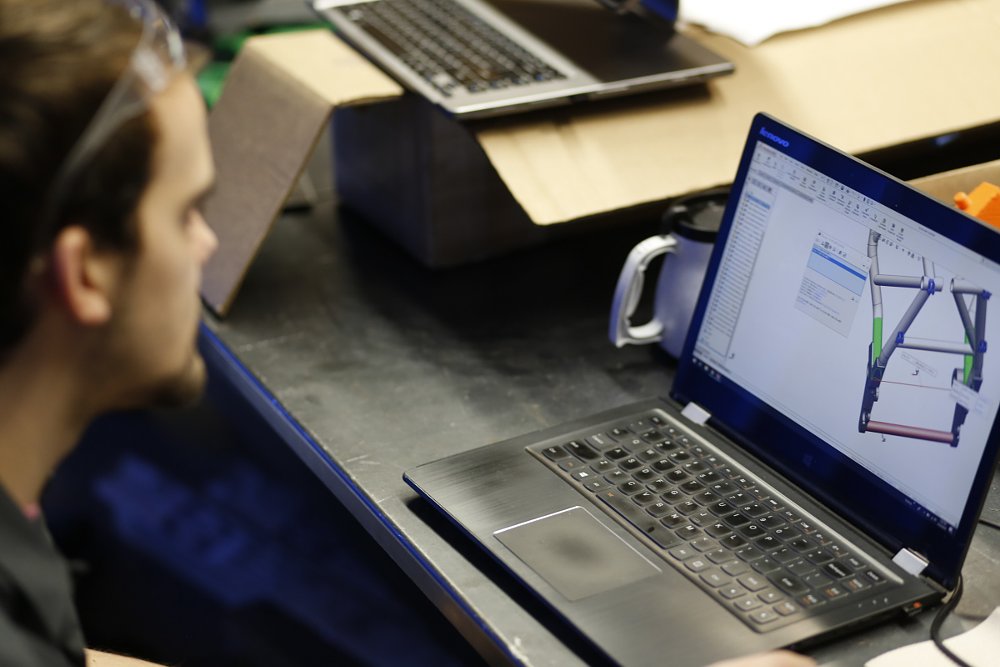

The RIT Pikes Peak project began with the acquisition of a used KTM Super Duke 990. The wheels, brakes, and suspension were left alone, but mechanical engineering students designed a new steel trellis frame that was better suited to housing a battery pack. Rather than delve into a complex vehicle dynamics problem, the students built a new frame that matched the original in key dimensions, such as the position of the swingarm pivot and shock mount, and the position and angle of the steering head. This was made easier by KTM, which supplied a CAD file of the original frame.

The team’s faculty adviser is Carlos Barrios, an engineering professor who has some pretty serious motorcycle chops of his own, mostly on the ADV/dual-sport/enduro spectrum. Barrios took pains to point out that unlike a lot of other EV projects, the RIT student team built its own battery.

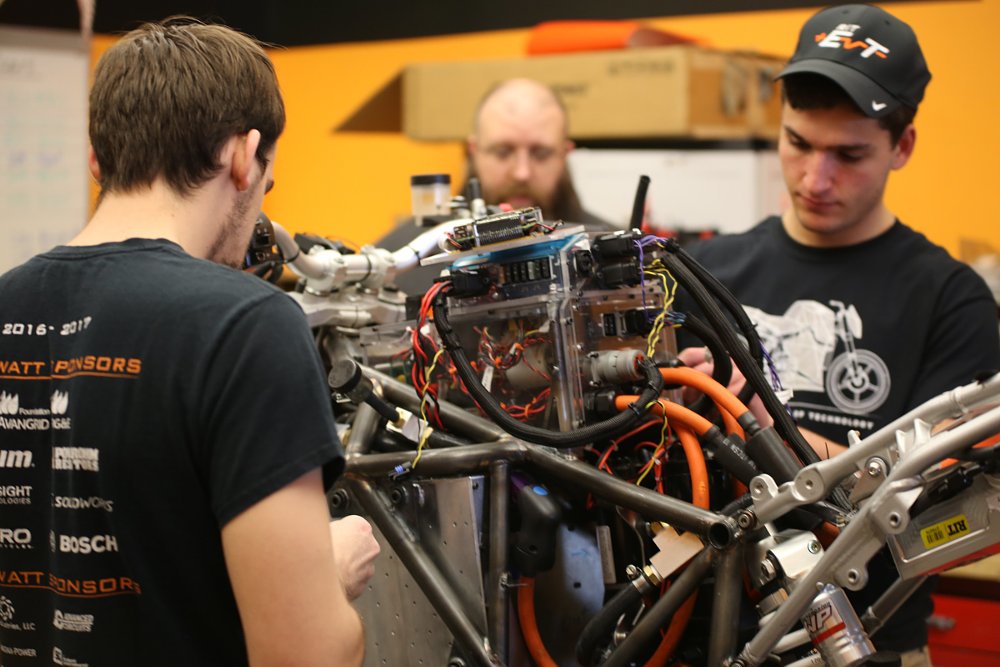

Ben Cooper, a senior in electrical engineering, explained that their battery design is a rectangular prism. It has four layers, each made up of 300 Panasonic 18650 cylindrical cells, the same cells Panasonic supplies to Tesla. The cells are packed in a machined aluminum sandwich, with coolant circulating inside the alloy plates. The finished 10.8 KwH pack weighs about 180 pounds.

There are two completely separate cooling circuits, one for the battery and one for the motor controller. The motor controller (that big metal box under the tail) is a Rinehart Motion unit. The purpose of this critical component is to take 400 volts of DC in and deliver measurable, controllable three-phase AC power out to the EMRAX 268 motor.

Rinehart recently merged with AMRacing and the Oregon-based company (a subsidiary of Borg-Warner) has been rebranded Cascadia Motion. They’re heavyweights when it comes to racing applications, having supplied many Formula 1 auto racing teams with KERS and ERS systems, as well as supplying winning TT Zero motorcycle teams.

I spoke to Larry Rinehart about the project, and he mentioned that in 1970, he was on a UC Berkeley team that raced from MIT to Caltech in an event billed as the "Clean Car Challenge." Evidently, Rinehart’s team thought a clean car was not enough of a challenge, so they built a motorcycle powered by lead-acid batteries and went coast-to-coast in six days. Rinehart just calls the controller an inverter, because it converts DC power from the battery to AC power for the motor, but it also manages the flow of power from the battery to the motor.

The 45-pound motor is about the size and shape of a lumberjack’s pancake breakfast. A lumberjack would, however, be hard pressed to do as much work, since the rig can produce over 300 foot-pounds of peak torque. Since that force is available at one rpm, you can see why the motor controller — which determines throttle response — is critical to making a beast like this rideable.

Some EVs run a separate Vehicle Control Unit between the throttle and the inverter, which could use data from an IMU the same way modern sport bikes do, for lean-angle-specific traction control. The RIT bike already has an IMU on one of two circuit boards located in what would have been the "fuel tank" area on the original Super Duke. Right now, they use the IMU for data capture only. There’s also an LTE chip, which could be used for real-time, remote data acquisition at some point in the future. Barrios told me that a more advanced setup, with a VCU, would be desirable but because it’s also safety critical, they’re not going to rush into it.

When I spoke to the team, they were limiting output to about 220 foot-pounds of torque and about 130 horsepower, but if testing and development goes well, the bike could have up to 50 percent more on tap.

The RIT design allows for the "countershaft" sprocket to remain in the right position for a direct drive to the rear wheel. They plan to gear it for a top speed of about 130 miles an hour, although the battery will significantly discharge over the course distance, so like an ICE entry, it will not have quite as much power available up top.

The final weight of their bike is nearly identical to the original KTM Super Duke with a full tank of fuel. So, the basic suspension would have been close to right. But they’ve taken it a bit further.

Barrios, the team’s faculty adviser, races KTMs. “Solid Performance KTM, near Philly, is the best KTM and WP shop on the East Coast,” he told me. “Our original bike was the basic ‘black’ version. Solid Performance helped us out a lot. They upgraded the suspension so that we’ve got the equivalent of the ‘S’ model, and set it up for us.”

Racing to the clouds: A tall order

The Rochester students recruited their rider, Jeremy Higgins, at The Leaf & Bean, a moto-friendly coffee shop in the Rochester neighborhood of Chili. Higgins is a pro flat tracker who’s made a few AFT Mains, so he’s not just some guy who talks a good game at the local Bike Night!

When I first started talking to the team, they’d actually only run the bike at slow speed in a parking lot on campus. They recently spent a track day at New York Safety Track, where Higgins was able to shake it down in a better test.

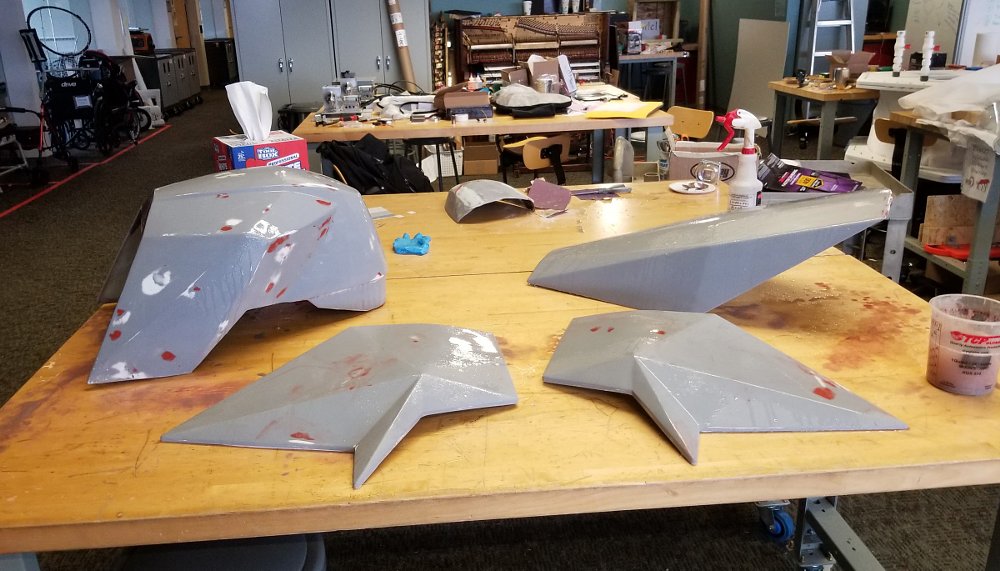

“It was good!” Higgins told me. “The kids building the bike are geniuses, but they don’t have racing experience. So I expected it to go mach seven down the straight, but would it turn? Honestly, we were out there with the old DOT tires that were on the bike when they bought it, and I was scraping the bodywork.”

Coming from a dirt-track background, it’s not surprising that Higgins jumped at the chance to race Pikes Peak. After all, dirt-track racers used to dominate on the old gravel course.

“Me being a racer,” Higgins said, “you think, ‘It would be cool to race Baja. It would be cool to race the Dakar.' Pikes Peak is another one of those bucket-list races.”

It’s a road course now, though. The last time Higgins had to adapt from his flat-track style to a road-race style, he picked it up quick — he made the cut for the very first U.S. edition of the Red Bull Rookies tryouts. But that was years ago, and Pikes Peak is made more challenging by limited practice opportunities. When the roads are open to regular traffic, there’s a lot of gawking tourists, and low speed limits are strictly enforced; there’s little to be learned. There’s one private, full-course practice day available for motorcycles this year, coming up soon, but RIT’s not attending.

Last but not least, each day, the motorcycles practice on only one-third of the course during official practice and qualifying. There’s an optional practice day listed on the schedule this year, but it’s not a full-course run either, so a rookie like Higgins will not see the entire 12.42 miles at race speed until the flag drops for real. He told me he’s been watching the onboard video recorded by Chris Fillmore on his record run.

The RIT EV team is cautious about defining a goal for the race. They’re entered in the "Heavyweight Motorcycle" class, where the only other EV is the official Zero entry, ridden by Cory West. There are two other EVs, another university entry from Nottingham, in England, and a Japanese entry that’s coming straight from the Isle of Man to Colorado, but they’re in the "Exhibition Motorcycle" category.

Beating Zero would be a big deal, as would beating the time set by RIT’s rivals from the Ohio State Buckeye team. (The Ohio team isn’t coming this year, but coming in under the Buckeye’s 2017 mark of 10:55.500 would give RIT some bragging rights.)

Practice for this year’s race begins Tuesday, June 25. The race is Sunday, June 30. The Rochester Institute of Technology team plans to send 18 students. It’s a fun event for spectators, in the middle of some incredible motorcycle country, so if you want a spur-of-the moment vacation idea, go cheer them on. I plan to check back with the team during practice and after the race, so watch for a race report in early July.

Membership

Membership