Riding to the top of Alaska is an enticing excursion for any rider and his best bud. But what about doing it on a Honda Trail 125 and its forebear, an antique CT90?

You’d have to be a little looney or have a really good reason (other than making a CTXP episode) to ride such slow, seemingly inappropriate machines all the way across the Last Frontier, a state twice the size of Texas.

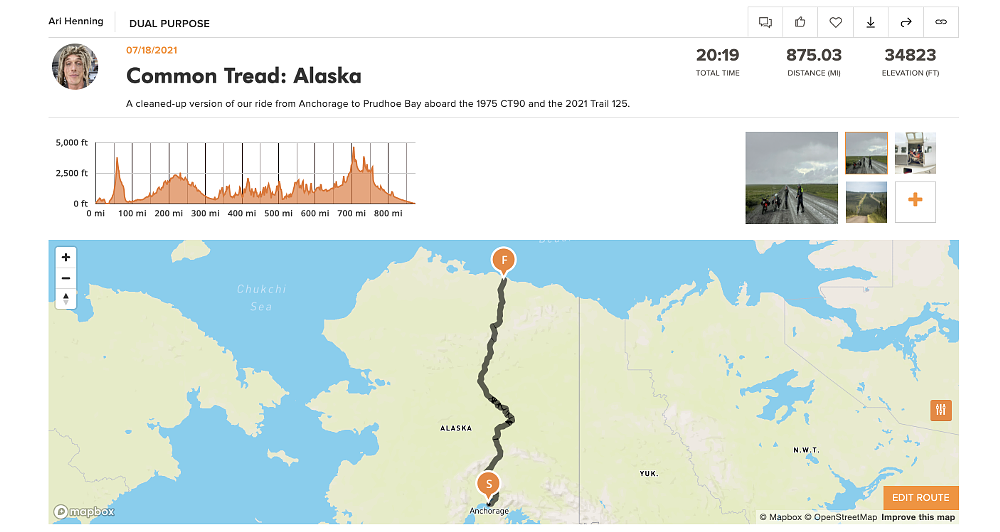

Zack and I would never deny being a touch daft — especially when it comes to road trips — but there was a coherent rationale for folding ourselves onto such small bikes. However, we wouldn’t get to capitalize on our decision until we reached the community of Deadhorse in Prudhoe Bay, which was still 1,000 miles north of our starting point in Anchorage, over several mountain ranges and at the far end of the notoriously dangerous, famously desolate, mostly gravel Dalton Highway.

Kickstands up

Every journey starts with a single step, and in this case that step was over the sloped down tube of a 2021 Trail 125 for Zack and a 1975 CT90 for yours truly. We’d sourced the (non-running) CT90 from a retiree’s garage in Orange County, California, just a few days before it and the factory-fresh 125 were to be lashed to a pallet for shipment to Anchorage, so there had been precious little time to tune it up.

I wish there had been, because as we motored north out of Alaska’s largest city (population 293,531) amidst a late-summer rainstorm, the CT was misfiring mightily. Zack also reported smoke puffing from the exhaust, perhaps with a note of amusement in his voice. After all, I’d opted to ride a vintage Trail as a counterpoint to the newfangled 125 because I thought it would have more character. This was a great reminder to be careful what you wish for. Zack’s Trail ran flawlessly, of course, with features like front ABS and 12-volt LED lighting, as well as undented steering-head bearings and intact fork seals to bolster his confidence.

Off the highway and onto a quieter back road that suited our slow touring rigs, we began to witness the grandeur that attracts so many to the 49th state. Birch, spruce, and black cottonwood grow tall and dense at this latitude, always with a backdrop of mountain peaks, the result of tremendous and constant tectonic activity. In the valleys between ranges, rivers flow in abundance, fed by the melting ice of ancient glaciers. We had ample time to appreciate the scenery; traveling slowly has its perks.

That afternoon we sampled our first dirt road en route to Hatcher Pass, intentionally ran out of gas to establish range on our laden-down bikes, and briefly barreled along the Parks Highway before veering off for the town of Talkeetna. Even though it was nearly 10 p.m. by the time we crawled into our tents, the sun was still well overhead, repelling sleep. During the summer this far north on the globe, Malina, the Inuit sun goddess, dips below the horizon only briefly, and she would follow an even higher orbit the farther we traveled.

Over the next two days, we did our best to make time through the Alaskan interior, but going is slow with seven or eight horsepower. The CT90 could only carry 45 mph on the flat and would maintain 38 to 40 uphill — with a tight draft off the 125. The old bike with unknown history was also consuming oil at a quarter of a quart every 200 miles. Pushing aside our concerns for the CT’s health, we motored on, skirting the Denali National Park and the broad, sediment-rich waters of the Susitna River, past the huge built-but-never-opened Igloo City Hotel, and into Cantwell, population 219. The tiny town stands at the western terminus of the Denali Highway, an epic ride in and of itself, but our front wheels tracked north as reliably as compass needles.

After nearly 400 miles on what felt like a rural back road, Fairbanks (Alaska’s second-largest city, population 32,515) came as a shocking melee of divided highways and urbanization. Merging onto State Highway 2 and dropping back down to two lanes, we said goodbye to civilization and hello to a new travel companion: The Trans-Alaska Pipeline.

Four feet in diameter, 800 miles long, and carrying 35,000 gallons of crude per minute from Prudhoe Bay in the north to the Port of Valdez in the south, the pipeline is the backbone of the Alaskan economy. The conduit’s southern section is buried, but north of Fairbanks, it breaches the surface and rises on pillars to prevent the hot crude from melting the permafrost substratum. The pipeline is a monumental feat of engineering, and in many places in northern Alaska, it and the Dalton Highway are the only signs of humanity.

Mile Marker 0

About 80 miles north of Fairbanks and approximately 500 miles into our trip, the real adventure was about to begin. We had arrived at Mile Marker 0 of the Dalton Highway. Known as the Haul Road to locals, the Dalton stretches 414 miles north to the Arctic oil fields of Prudhoe Bay.

We had heard a lot about the Haul Road, nearly all of it in the form of warnings that boil down to the fact that out here, there is very little room for error. Sure, the gravel road surface can be unpredictable, but it’s also piled high above the tundra to insulate the underlying permafrost. That often makes for a steep, four-to-eight-foot drop off either shoulder, and there are no guard rails. Rises and blind turns are common, and you’re sharing the route with big rigs making supply runs. The truckers know the Haul Road like the backs of their hands, and drive like it. Even when they slow down to pass you, they leave a storm of dust and flying rocks in their wake. Then there’s the extreme weather, grizzly bears, hordes of mosquitoes, and the simple reality that when you’re this remote, help is a long, long way off.

It seemed like if we needed assistance, it would be because the CT90 holed a piston. Forty years past the prime of its life, it was enduring long days at near-constant WOT. It kept running, though, climbing steep grades with a helpful push from Zack and his understressed, crisp-running 125. We’d anticipated a lower average speed on the Dalton, but the road was smooth and truck traffic was light, so we were making excellent time.

On the north side of the wood-surfaced Yukon River Bridge, we stopped to fill up from an above-ground gas tank and reference the map. We still felt reasonably fresh and had an inexhaustible supply of daylight, so the decision was made to leapfrog our intended campsite for the night and push on for Coldfoot Camp, which was another 125 miles up the road and the last outpost before the 250-mile final slog to Deadhorse.

By later afternoon we’d crossed into the Arctic Circle, the latitude above which the sun remains above the horizon for at least one day each summer. It was too late in the year for a true “midnight sun” experience, but we rode well into the still-bright night getting to Coldfoot Camp.

Like the Haul Road itself, Coldfoot Camp (population 34) was established to help build the pipeline. What remains is little more than a collection of low buildings that include bunk houses, a garage and cafeteria, plus a few gas pumps in the dirt parking lot. It doesn’t sound like much, but it’s a proper metropolis compared to the utter absence of resources on the remaining 250 miles of the Haul Road.

Our last day on the Haul Road was long and eventful. We summited the razorbacks of Atigun Pass in the Brooks Range and rode through rain, marble-size hail, and lightning on the Arctic tundra. Other than this storm and the occasional shower, the weather had been quite mild throughout our trip, but 15 miles outside of Deadhorse a dense fog enveloped us, frigid and penetrating. Rolling into Deadhorse (official population 25, but with a non-permanent population of about 3,000 oil workers and support crew) was a relief. When we finally pulled up to our hotel — a massive, modular structure on concrete pillions — we were too cold, tired, and hungry to think or speak clearly.

We’d warm up, rest, and eat, but our adventure wasn’t over yet. After all, we’d ridden these silly little bikes this far for a reason.

The northernmost point in the United States

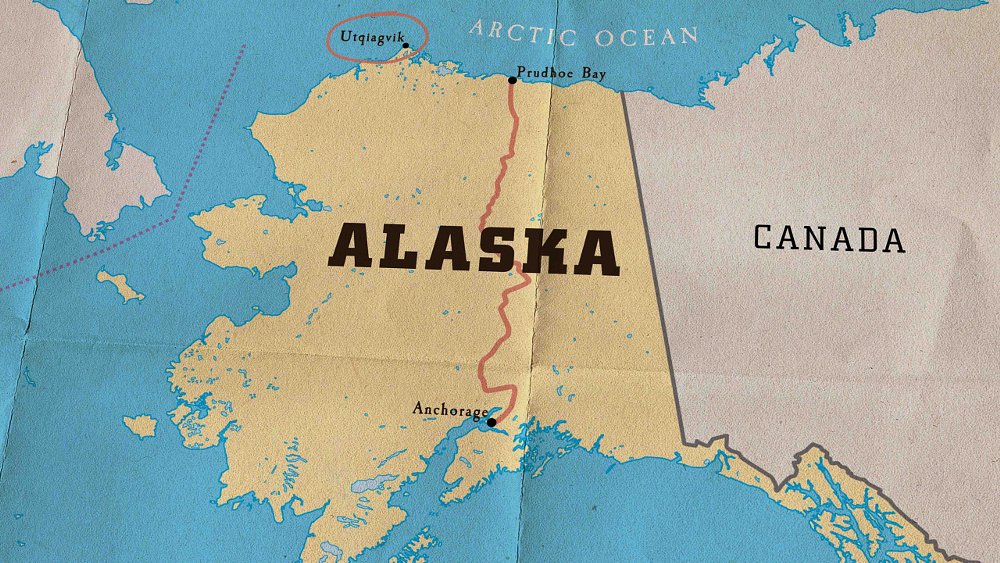

I have to imagine that when most tourists arrive in Prudhoe Bay, they see where the Haul Road T’s at the wetlands of the Arctic Ocean and feel satisfied thinking they’ve reached the top of Alaska. That’s a fair assessment if your criteria is to travel by land, but many of Alaska’s communities are only accessible by air. That includes the town of Utqiagvik (read: oot-key-ag-vik), which sits a few miles south of Point Barrow, the true northernmost point in Alaska and thus the northernmost point in the United States. That was our destination, and the reason we’d opted for pint-size adventure bikes.

A pair of BMW R 1250 GSs or a couple of Kawasaki KLR650s like those available for rent in Anchorage would have been ideal for the 1,000 or so miles we’d covered in the previous five days, but those bikes might not have fit in a Cessna Grand Caravan. The Trail 125 and CT90 rolled into the single-prop plane beautifully, however, and we didn’t even have to fold the handlebars down or take off the mirrors. And in no time we were soaring over marshes, lakes, and trough ponds, features that make roads nearly impossible on the Arctic Coastal Plain.

We touched down in Utqiagvik (population 4,383), unloaded our bikes, and began to get our bearings. Native Inupiat people have inhabited this far corner of the world for at least 1,500 years, surviving on fish and whale meat. The current residents still row out onto the ocean to whale, as evidenced by two freshly butchered beluga carcasses on the beach. The roads of Utqiagvik are dirt and the homes are humble and weathered, and often feature a slab of bowhead carcass sitting in the yard. No need for refrigeration when you’re this close to the north pole.

As bizarre as it appears, Utqiagvik has all the trappings of a normal town. There’s a fire station, schools, a hospital, supermarket, and post office. Amazingly, I was able to send my dad a postcard for the standard $0.40 rate. Way to go, USPS! Everything else however — food, clothes, and other goods — are priced at four to five times what you would pay in the lower 48 due to the fact that every item has to be flown or shipped in. Luckily, the town and its residents are fairly well funded with dividends from the oil companies, who pull as much as two million barrels of crude from the ground on a daily basis.

Some of that oil may have been in our engines, which we were now hoping would have enough stamina to carry us 10 miles out of town and up the beach to Point Barrow. We headed north in a light, cold rain, past whale skulls the size of golf carts, past the abandoned Marston Mat runway that was used to fly in DEW Line equipment during the Cold War, and finally, past the lines of fish-camp shanties.

When the two-track road disappeared into the beach sand, our progress ended. The gray sand swallowed our narrow wheels and slowed us to a stop within feet. And we still had three miles to go. Airing down our tires only made the bikes easier to push; riding wasn’t an option unless we found firmer ground.

Unfortunately, the hardest sand was that which had been compacted by the surf, and as we flailed along the shore waves of salt water lashed out at us, steaming off our hard-working engines. For once, the CT90 seemed to have an advantage. With the sub-transmission flipped to low and the oversize Shinko SR 241 tires providing a bigger footprint, I was making better progress than Zack on the 125. It didn’t last though. The seawater must have shorted out the CT90’s decrepit ignition system, because as the telephone pole that marked Point Barrow came into sight, the bike died and refused to restart.

Zack circled back and mercifully helped me push the bike the last quarter mile through the sand. We were tired, sweating profusely in our rain gear, and had heart rates that would have set off alarms on a Peloton, but we’d made it.

Standing with our boot toes nearly in the Arctic Ocean, we looked left, and the beach curved to the south. Looking right, it curved south. There was no question that we were standing at the edge of the northernmost point of Alaska, which now, finally, felt like the right reason to have travelled so far on such small bikes.

Membership

Membership