“The brakes were shit and the shocks were garbage, but the H1 was the fastest thing on the street.”

That’s the summary offered by 84-year-old Tony Nicosia, who was a 31-year-old champion drag racer when he joined Kawasaki’s nascent American arm to help develop Kawasaki’s now-legendary H1 Mach III two-stroke.

When the H1 debuted in 1969, it was the fastest production motorcycle on the planet. Tony repeatedly posted mid-12-second quarter-mile times in early testing, figures some magazines suggested were fictitious and initially refused to publish. With speed like that, and a price of just $999 (about $7,300 in today’s money), H1s sold like crazy, and put Kawasaki on the map as a performance brand.

Many have heard about the scorching-fast H1 triple and the wicked 750 cc H2 that followed in 1972, but what few people realize is how early in Kawasaki’s two-wheel lineage the H1 arrived (Kawasaki built its first-ever motorcycle in 1962), and how effectively it catapulted Kawasaki to the forefront of the largest motorcycle market in the world while simultaneously raising the bar on the entire industry.

Roll it back to The Swinging Sixties

In the 1960s, a mid-14-second ET was considered quick for a stock motorcycle, and bikes like Harley’s Sportster, Triumph’s Bonneville, and BSA’s Super Rocket were the top choice for performance-minded riders. Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha were fairly new arrivals to the U.S. market, and had just begun developing bikes for power-hungry, speed-crazed Americans.

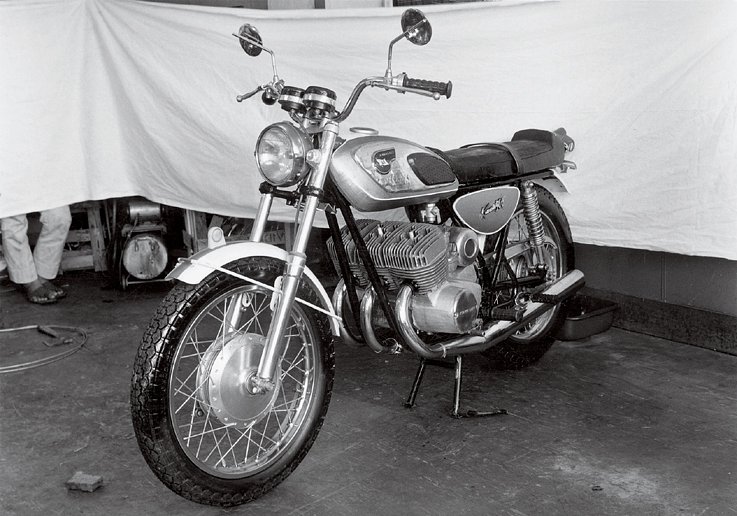

It wasn’t until 1966 that Kawasaki joined the fray, hoisting the River Mark flag above Southern California soil with a skeleton crew and only three models on offer: the 250 cc A1 Samurai and 350 cc A7 Avenger two-strokes, and the BSA-inspired 650 cc four-stroke W-1.

If Johnny-come-lately Kawasaki was going to gain a foothold in the United States, it needed a bike that would amaze buyers and shock the industry. After surveying the competition, criteria were established, and, as with all great engineering programs, given a code name. The N100 Plan called for an air-cooled 500 cc engine making no less than 60 horsepower, with a quarter-mile time of 13 seconds or faster. And, it had to be affordable, because if the N100 Plan was going to make Kawasaki a household name, then the bike not only needed to be impressive, it also needed to be prevalent.

A two-stroke was the only way to hit the target. Conveniently, the Clean Air Act was just a glimmer in Congress’s eye in the late 1960s, so Kawasaki engineers in Japan approached the project from two angles. The first involved boring out the existing A7 Avenger to 500 cc, and the second entailed designing an all-new engine.

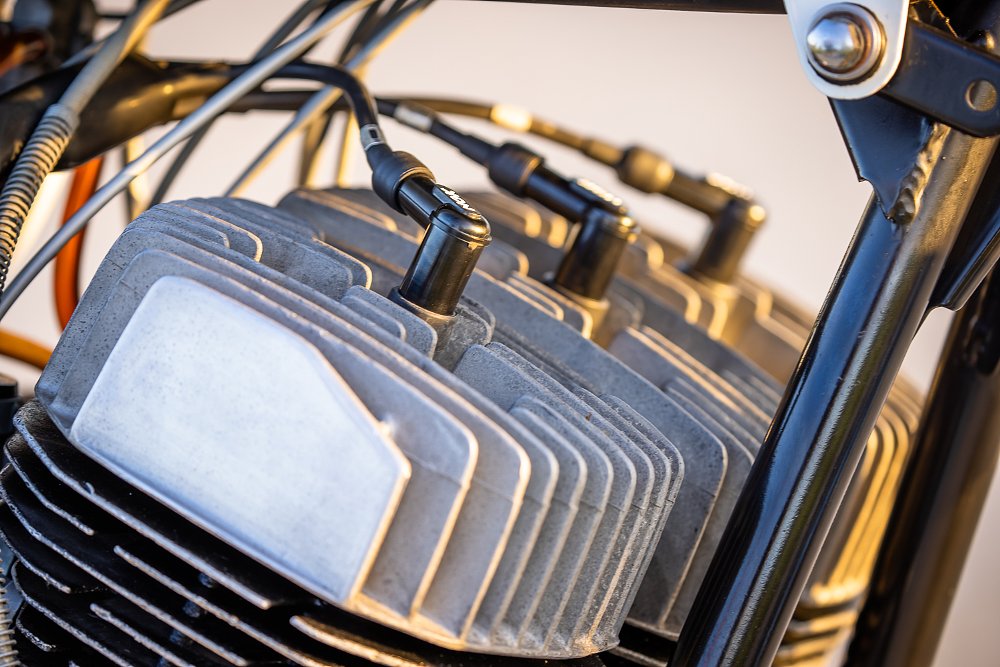

A triple would stand out among the ubiquitous twins and provide the port area needed to make big power, but keeping the center cylinder cool was a concern. Kawasaki leaned on Osaka University’s engineering department to determine the optimal cooling array, with the final design featuring slightly inclined cylinders cloaked in inches-long fins. A CDI ignition system — the first offered on a production bike — controlled once-per-revolution spark, while an oil-injection system handled lubrication. For ease of production and cost savings the engine eschewed a rotary valve in favor of piston porting, and gulped mixture through a trio of 28 mm Mikuni carburetors.

While the H1’s three-across engine was cutting edge, the chassis was status quo, which is to say wholly inadequate for a powerful motor that came on hard at 6,000 rpm. The frame was a conventional thin-tube double cradle with sloppy plastic swingarm bushings, frequently faulty shocks, and toothpick-like 34 mm forks that Tony says were filled with varying quantities of “fish oil.” Worse yet, the whole 400-ish pound, blistering-fast package was meant to be slowed by a pair of impotent drum brakes.

In the end, all that mattered was the speed. “People wanted fast things, they didn’t give a shit if it handled,” says Tony. Fair enough. After all, this was an era when drag racing was hot and ETs were the

Then, there was the nickname, whispered in awe at dealerships, drag strips, and bars. “The H1 really was the first widowmaker,” recalls Tony, though the moniker stuck more tenaciously to the 50% larger H2 that arrived in 1972. “It was a term from the board-track days, but we [test-rider Tony and Kawasaki’s Advertising Manager Paul Collins] used it on the H1 because of the way it might flip over backwards and spit you on the ground, or get a wobble at high speed. It was just a nickname, but it caught like wildfire.”

Riding the “triple with a ripple”

It was one thing to talk about the H1 with Tony, but it’s another thing to actually ride one of these icons. Luckily, a friend has a first-year H1 that I was able to throw a leg over. Larry grew up at the tail end of the two-stroke era and has always revered the triple, so when he spied a debased survivor in the garage of a house he was interested in purchasing, he negotiated the bike into the sale. “I told the seller I’d buy the house, but the bike had to stay in the garage.”

Now fully restored with Higgspeed chambers, modern Continental tires, Hagon shocks, and equal volumes of ATF in the fork legs, Larry’s bike is about as pristine as a regularly ridden, 52-year-old motorcycle can be.

When you hop on the bike it feels long and narrow. Looking down, however, the finned cylinders protrude beneath your knees and there’s a full 22 inches of cast aluminum between the stator cover that bookends the left side of the motor and the distributor and oil pump on the right. The dash is the picture of simplicity: Two chrome-bezel analog gauges tempting your eyes clockwise toward the extremes of the needles’ sweep.

There’s little compression to resist the kick starter, and the engine fires up easily. Straight-line speed dominates H1 mythology, but a close second is the cackle of that angry triple. That sound

And let’s not forget the dense and aromatic fog that wafts around a running H1. Famously over-oiled by the throttle-controlled Injectolube system, arrows of blue smoke shoot from the exhaust tips like muzzle fire when you blip the throttle.

After pulling in the heavy clutch lever and clicking up into first from the neutral-at-the-bottom five-speed transmission, we’re underway with surprisingly smooth and tractable power at low RPM. Steering is light and stable with the friction steering damper half tight, and other than the brutal, head-turning, eye-widening din that ricochets from the bike any time you open the throttle, it’s a perfectly amenable machine that feels a lot like any number of other UJMs.

Of course, the H1 legend wasn’t built on its around-town demeanor. With a straight stretch of vacant road, I steadily lift the carburetor slides to wide open. In short order the hollow whaaaahhh from the K&N pods is overpowered by shrieking exhaust. The engine surges and falters in the midrange before clearing its throat and accruing revs at an exponential rate. Classic two-stroke.

The acceleration pushes my butt back on the bench seat as the front end gets light, and I’m given a taste of a scenario that could put an unsuspecting rider on their ass in a hurry. Second, third, fourth, and fifth gears blur by as the engine howls and the speedometer needle climbs. The H1 was reputed to have a top speed of 118 mph, but I’m satisfied with the ton, knowing all too well that the Mach III would need a lot of runway to slow down. As Tony said, the brakes are shit.

I made a few more mock drag sprints, but never experienced the high-speed instability that contributed to the H1’s notoriety. Surely the Continental radials help, as well as the reworked suspension. The bike even corners well enough, at least until a bump is introduced to the equation. Then the wheels bounce and the chassis wallows in a chaotic dance that’s pretty unnerving, and would certainly be scarier at speed on Dunlop K87s and stock suspension.

A little H1 goes a long way. Kawasaki’s 120-degree triple has perfect primary balance, but there’s a nasty rocking couple that is accentuated by the width of the crankshaft. At higher engine speeds, a powerful fizzle infiltrates the balloon grips, seat, and footpegs and leaves your backside and palms tingling and itchy. And the cacophony that accompanies you, through earplugs, is exhausting in its own right. Then there’s the gas mileage, which teeters in the upper teens when you’re wringing the triple’s neck. This bike is easily as polluting as a half-dozen modern, catalyzed machines with twice the displacement.

It’s a loud, smokey, inefficient machine, but boy is the H1 a thrill to ride. Even if it isn’t fast by modern standards (A Suzuki SV650 would best it everywhere except weight. We’ve come a long way!), it still feels quick, which is saying something. The power comes on hard and fast, and of course it’s all intensified by that sound. It’s easy to see how this machine made an impression. It certainly made one on me.

A lasting legacy

With the N100 Plan, Kawasaki wanted to shock the world. The H1 Mach III was like an F4 Phantom’s sonic boom rattling the windows of every corporate office that fancied itself a motorcycle manufacturer. The bike’s speed immediately made the slow-revving, pushrod four-strokes of the day obsolete, while forging Kawasaki’s image as a performance brand.

The bar had been raised, and manufacturers were forced back to the drawing board for fresh designs. Tightening EPA mandates were making two-strokes less viable, so ever-larger and more technically advanced four-strokes were needed to achieve the performance riders expected. Honda struck back with its iconic CB750, and Kawasaki’s own follow up to the H1 and H2 triples was the massive 903 cc Z1.

The new era of inline-fours had begun, and it was catalyzed by the shrieking two-stroke triple from a little-known Japanese manufacturer. In its day, the H1 was the fastest bike on the street. Nowadays, just about everything with a whiff of sporting prowess is faster. And thankfully, anything you buy now will have far better brakes and suspension.

Membership

Membership