They don’t make ‘em like they used to. It’s a cliché commonly ascribed to grizzled old-timers — especially in the moto-sphere. But when it comes to scramblers, the cliché mostly rings true. Mostly.

Today’s scramblers hardly bear the off-road distinction bestowed upon their forebears. Good luck finding a Triumph Scrambler 900 far from pavement. Same goes for BMW’s R nineT Scrambler. These “heritage” models are content to co-opt the scrambler look. It’s no wonder owners rarely risk denting the polished bodywork with flying gravel or, worse yet, full-on tip-overs.

Are these retro renditions all that different from scramblers of yore, though? Aside from the Ducati Scrambler line, manufacturers base today’s models on existing platforms. Honda’s SCL500 owes much of its existence to the Rebel 500 cruiser. Triumph’s Scrambler 900 shares the DNA with the Speed Twin 900 and BMW’s offering is a derivative of the base R nineT. It’s important to note, these measures date back to the category's inception.

Back in my day

The scrambler came of age in the 1960s, but its roots were established in the early 20th century. First held in Carlisle, England, in 1914, the International Six Days Trial forced racers to modify their machines for dirt roads. By the ‘20s and ‘30s, a new form of racing prompted riders to make it from point A to point B in the shortest time possible, regardless of route. The path of most resistance almost always proved the fastest, incentivizing off-road shortcuts.

These mixed conditions — and resulting mayhem — gave rise to the term “scramble.” Eventually, manufacturers caught on. And Triumph struck first. In the mid-1950s, Hollywood stuntman and Triumph dealership owner Bud Ekins found success racing the TR6 Trophy. The Brits capitalized on those results with the TR6 SC and the Bonneville-based T-120TT/T120C production models.

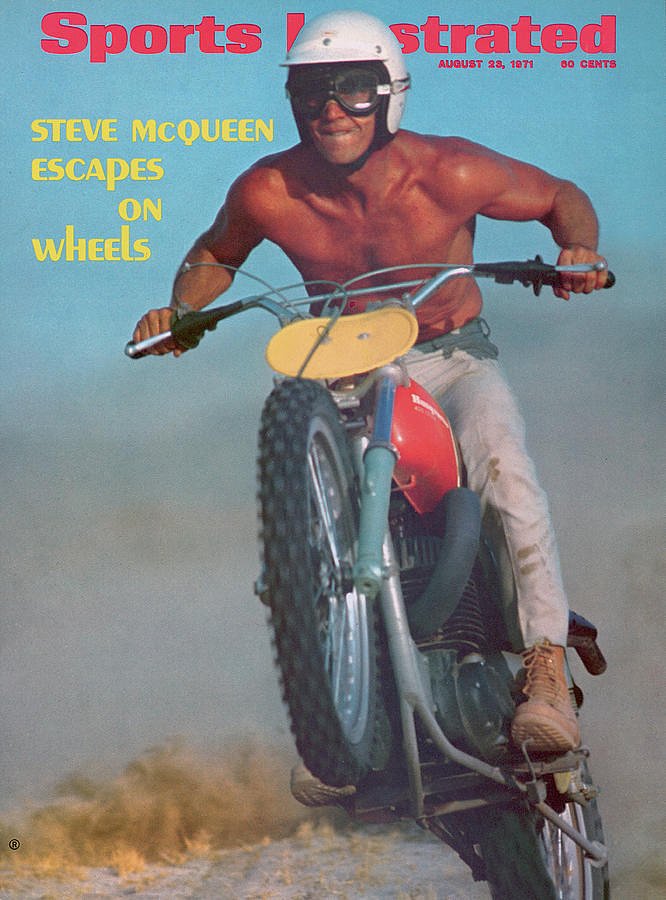

Triumph was far from the only option in the space. Rivals from Spain’s Montesa to Britain’s BSA to Japan’s Honda all vied for scrambler supremacy. For some, Triumph’s example served as a blueprint, with Honda’s CB series serving as the foundation for its CL scrambler line. By the mid-1960s, the scrambler reached its peak, popularized by Hollywood star and desert racer Steve McQueen.

The style achieved mass appeal when the King of Cool participated in the 1964 International Six Days Trial. It fully matured by the time Bruce Brown’s 1971 film “On Any Sunday” hit the silver screen. The exploits of racers like Malcolm Smith and McQueen inspired an entire generation of riders. To this day, their feats are no less impressive, especially when considering the motorcycles of the day. Motorcycles that weren’t much more capable than today’s reimagined scramblers.

Far from the tree

Naysayers often reduce the contemporary scrambler to a design exercise. That’s a fair assessment, given today’s hyper-specialized landscape. When dirt bikes boast more than 12 inches of suspension travel, neo-scramblers seem torturous by comparison. Yet, these modern classics don’t fall far from the tree.

Triumph’s Scrambler 900 and BMW’s R nineT Scrambler offer the least in the suspension department. The former yields 4.7 inches of wheel travel (at both ends), while the Beemer benefits from 4.9 inches fore and 5.5 inches aft. The Honda SCL500’s fork and dual shocks marginally improve on those numbers with 5.7 inches and 5.9 inches, respectively. Narrowly topping the heap, Ducati’s latest-gen Scrambler clocks in with 5.9 inches of travel all around.

Oftentimes, preparations were worse back in the day. At the shallow end of the pool, the race-bred Norton-Metisse (1966-1967) conquered the trail with as little as three inches of suspension travel. Conversely, Montesa luxuriated its 250 Lacross with 6.5 inches of travel in 1966. These figures roughly align with spectrum of present-day scramblers. There’s one major difference: We don’t ride scramblers like we used to.

The original scramblers were the dirt bikes of their day. What riders lacked in suspension technology they made up for in moxy (and a dash of blissful ignorance). That’s not a compromise motorcyclists have to make nowadays. Serious off-roaders have their pick of the litter, including dirt bikes, enduros, dual-sports, and adventure bikes. Scramblers, on the other hand, are conducive to collecting cool points and occasionally exploring fire roads. Not all scrambler-styled models are as trail-averse, however.

The exception to the rule

Released in 2019, the Triumph Scrambler 1200 XE couples old-school scrambler form with adventure-bike function. That’s what a 21-inch front wheel and 9.8 inches of suspension travel does for a bike’s dirt cred. For several years, the XE wasn’t the only performance-oriented scrambler on the market. The Desert Sled also elevated Ducati’s Scrambler platform with off-road-worthy componentry. But good things don’t last forever.

The Italian firm will officially discontinue the Desert Sled variant following the 2023 model year. Ducati’s decision doesn’t just downsize the scrambler market but also re-establishes its emphasis on aesthetics. The latest category entry, Triumph's Indian-produced Scrambler 400 X, certainly ticks the boxes cosmetically. Luckily, it doesn't completely abandon capability. Sporting a 19-inch front wheel, nearly six inches of suspension travel, and 395-pound curb weight, the newcomer isn't as trail-handicapped as its mid-sized counterparts. Let's be clear, though, the 400 X is, by no means, a dirt demon. The model's cast wheelset and low-mounted exhaust keep such off-road expeditions within reason.

It’s clear to see, manufacturers don’t make scramblers the way they used to. Considering the technological advancements of the last six decades (liquid-cooling, ABS, etc.), how could they? Despite all those changes, scramblers of today aren’t all that different from those of the golden era. What’s really changed is how riders use them.

Membership

Membership