The year is 1996 or thereabouts and at age nine, I just wanted to watch some locals do their best Jeremy McGrath impersonations. Well, the police who swarmed that sprawling sand pit seconds after our arrival had other ideas.

We were only passing through and got off easy, but those riders who'd already been forced out of the other vacant lot across the street — which we'll visit in just a moment — likely weren't as lucky.

So it goes in the off-road realm, where legal filings and land deals have made convenient riding a thing of the past. The local motocross track that was a 30-minute drive from your garage? Swallowed up by noise complaints and cul-de-sac construction. Those empty fields and abandoned work sites where kids on minibikes reveled in the blind eye of authorities? Litigation ended all that. Even woods riders who long ago lost Barkbuster-banging single-track have seen motorized recreation curtailed or pushed out completely in the name of environmental preservation.

Despite these seemingly ceaseless trends chipping away at off-road access, some competition-only and leisure-oriented facilities have enjoyed decades of success while doing the delicate dance of concessions, contributions and conscientiousness. One thing's for sure though — it wasn't always this way.

"There is that narrative of how it used to be better," Nick Haris, an American Motorcyclist Association (AMA) representative, said of those rose-tinted days when riding was cheap, plentiful and bureaucrat-free. "The world has changed."

What follows are a few examples of what can happen when prying eyes place a magnifying glass over your cherished track or trail. Some crash and burn, with the loss lamented for years to come, while others go with the twists and turns of outsider demands and even teach us a few things along the way.

Riding on hallowed ground

Some say the Roman Catholic Church is the largest non-government landowner in the world and its Catholic Youth Organization (CYO) supports sports and recreation. So, ending up with a motocross track in the church's property portfolio almost makes sense. Think it would happen today? Forget about it. But that's exactly what Charlie Weston, the late founder and president of the Blackwood Moto Enduro club in southern New Jersey, pulled off 50 years ago.

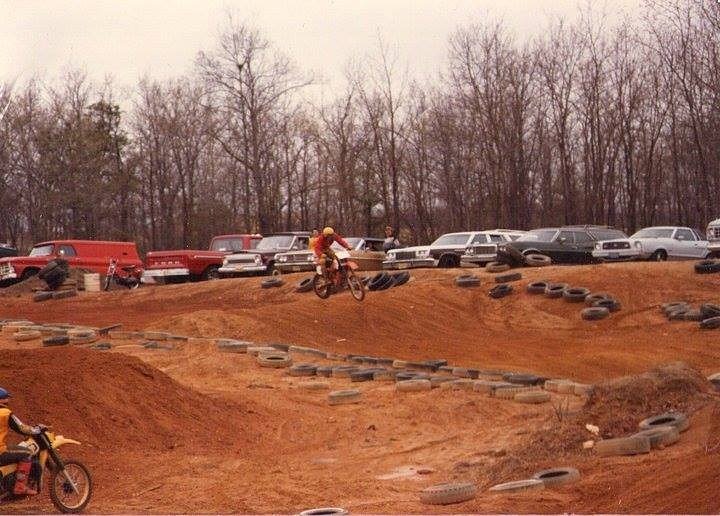

Weston, an employee of the CYO, got the blessings of the local Catholic diocese to lease a portion of their land next to the CYO, according to former club officials. There he created New Jersey's first true off-road vehicle park and it thrived between 1972 and 1985. Club members, who paid annual dues for the privilege of burning Bel-Ray bean oil, readily recall the good times. Plows and hand tools groomed the course. Everybody and their cousin knew that Bob "Hurricane" Hannah once rode there and blew the doors off the record lap time. Newbies learned to ride RM80s with their dads while the fast guys made life-long friends. It was a microcosm of early motocross in America.

Many say an injury lawsuit against the CYO, despite the club having a robust insurance policy, shut things down and the diocese — which did not respond to multiple requests for comment — just wanted to unload the land.

With Blackwood closed, riders moved to the surface-of-Mars-looking sand pit (seen in the old video above) across the street, where I was a spectator as a kid when the police showed up to put an end to that riding. Eventually, that lot was built into a world-class community park with more than half a dozen sports fields. Meanwhile, the other lots, where the CYO building was long ago demolished, and where the old Blackwood track used to be, are the same as ever: a barren stretch of yet-undeveloped land covered in loamy red sand just begging for a wheel to turn in anger.

How to win friends and influence policymakers

The issue at hand is hardly a new one and the four horsemen of moto-pocalypse are often to blame: injury lawsuits, encroaching development, environmental concerns, and pushback from neighbors or local government. If you've been around long enough, chances are you had a Blackwood of your own that fell victim to the aforementioned threats. They had names like Steel City, Speedworld, Saddleback Park, Indian Dunes, Pepperell, Aquasco, Kenworthy's or even Carlsbad. Take a tour today and, like historic battlefields, there's only faint hints of churned earth dug by the riders and machines who fought there.

What's a hotshoe to do? Well, to borrow the title of one of the world's best-selling self-help books, riders themselves could certainly try and win over skeptics or influence movers and shakers with good behavior. Rest assured, the AMA is also on the case. Its stance on off-highway vehicle (OHV) parks is quite clear: support "responsible recreational access to public lands for the use of off-highway vehicles" where "access should be administered by professional land managers to meet the needs of participants, protect the land, and promote responsible use."

Said another way: "Do everything you possibly can to stay and continue to be a good neighbor," Peter Stockus, the AMA's manager of Off-Highway Government Relations, relayed when asked about advice for tracks and trails looking to keep things hunky-dory with the locals. Case in point: He's been working with a long-standing hillclimb event in Massachusetts that's recently hit resistance on its way to the peak.

"One thing that's worked well in their favor is they've been a community partner for 40 years," he said. Being a "community partner" can mean having folks around town who know you and just recognize your operation contributes to the area.

"The stronger argument you can make on economic development, the better shot you've got," Stockus said of motocross tracks and trail systems seeking local approval for new or continued operations.

"An opportunity for entrepreneurs"

One example of a riding area that won support in part because of that economic development argument was the Hatfield-McCoy Trails system, which opened in southern West Virginia in late 2000. It has since expanded to more than 1,000 miles of trails in 14 counties that link to numerous communities and had a total economic impact of more than $68 million in 2021, according to a study by Marshall University researchers. It's a win for all involved, says longtime Hatfield-McCoy Regional Recreation Authority Executive Director Jeffrey Lusk, not only providing legions of dirt diggers with a place to ride, but also creating opportunities for entrepreneurs who want to serve them.

"You can't build a tourist economy where there's no capacity," said Lusk. The Hatfield-McCoy trails changed that. The town of Gilbert had one lodging option prior to the trail's arrival; it now boasts 200 beds across 17 providers within a five-mile radius.

"We provide an opportunity for entrepreneurs to come and set up a business," Lusk said, adding that one-third of the immediate region's spots to sleep are owned by those who came from out of state and took a chance. Now, Lusk says a "mini-economy" has "pooled up around the trail system" and amenities are an important part of the visitor experience.

Ever return from a race weekend and dread looking at your bank account? If so, you won't be surprised to hear that the Marshall University study found that on average a Hatfield-McCoy rider shelled out more than $150 on meals, roughly $90 while shopping, $90 in repairs, plus $80 in other forms of entertainment and attractions.

Another way the trail system is a community partner is by working with industry. Hatfield-McCoy has more than 100 agreements to use small portions of the vast amounts of land owned by various coal, timber, and gas companies, without interfering with ongoing industrial operations. What is and isn't in-network is clearly marked so those venturing beyond risk running afoul of internal policing forces and getting hit with hefty fines plus a court date. Those who stay on track and pay for the $50 permit — the price hasn't increased since 2007 — will likely enjoy as much off-road fun as one can pack into a weekend.

The key to having more places to ride, Lusk said, is to "show how the existence of trail systems is a positive for your community."

Unadilla: Less is more?

The gates at Unadilla Motocross will only open three times this year. (Its biggest event, the Parts Unlimited Unadilla Pro National MX Weekend, happens this weekend.) Jill Robinson, who since 2010 has managed things alongside her brother, says it's all part of a balancing act that keeps "Dilla" in the good graces of its upstate New York neighbors.

It's safe to say they've got it figured out. There's a long and proud tradition of top talent tearing it up at Unadilla, which has hosted global and national championships since the 1970s. Jill Robinson says her father, Ward Robinson (who died this week at age 85), "timed it brilliantly" when he opened the facility 53 years ago on lush land where rolling hills helped shape the allure of this rugged natural track. Those first face-offs between European experts and American challengers helped cement Unadilla's mystique, much like Daytona or Fenway Park, she said.

Such lasting success doesn't come easy, however.

"It's about a thousand hours of my life I'll never get back," Robinson recently joked while explaining the vast amount of meetings, paperwork, and coordination required to host a round of the 2022 Lucas Oil AMA Pro Motocross Championship. "There's a lot of hoops."

The juice, of course, has got to be worth the squeeze and when outside money comes to town, the regional economy sees it trickle down into pizza shops, gas stations, hotels, and plenty more stores. As a hand that feeds, Robinson says the track tries to give back locally as much as possible and makes sure area businesses have the track's event schedule well in advance so they can plan for stock and staffing.

Robinson said she was particularly impressed with tracks that offer near-daily riding opportunities instead of the few per year that Unadilla offers — tracks such as Southern California's Glen Helen Raceway, as well as Fox Raceway, which operates on tribal lands in partnership with the Pala Band of Mission Indians.

The pastoral nature of Unadilla's surroundings near New Berlin, N.Y., helps put a buffer between the track and both new and longtime neighbors that can keep complaints about noise at bay. On one hand, she wonders if electric motorcycles might eventually be the answer for densely populated areas where dirt bikes might not be welcome. On the other hand, she knows it's the racket of ring-a-ding ripping that's a real "lure" for many in this sport, regardless of whether it comes from a 1974 Maico or a 2023 Gas Gas. As someone who rode two of the record-setting 1,356 vintage motorcycles that lined up for Dilla's 11th annual MX Rewind in June 2022, I have to say, yeah… the deafening din seconds before the gate drops is gonna be a hard act to follow.

Ghost riders

You've seen it in the classifieds countless times: "Only selling because no time to ride." While the COVID-19 pandemic triggered a huge spike in off-road motorcycle sales, which was a boon for the sport, the flip side is that these people need places to go ride the new toy. Build it and they will come; shut it down and those too fed up to care or too young to know better are going to get out there in places where they shouldn't. That can have tragic consequences and spread anti-motorcycling sentiment.

There are possibilities for smarter utilization of land that would create riding opportunities closer to where many people live: using county fairgrounds, industrial park land, or empty parking lots at dead shopping malls. But for now, the bottom line is the same as it was many years ago when I reported on sanctioned dirt riding in the Garden State: legal off-road spots can be few and far between and you have to be prepared to spend quite a bit of time and money if you're going to do it by the book.

"It was a little piece of heaven," former Blackwood rider Larry Myers said of a simple sand pit in South Jersey. The trails, cut some five decades ago, still crisscross the land of sugar sand. The whitewall Sears car tires once used to mark the motocross track remain scattered about. In historic aerial images, you could damn near see 'em from space. On a recent rainy summer day, it was just a wall of faded "No Trespassing" signs where the wind, not wide-open two-strokes, howled through the trees.

It wasn't always this way, and Myers knows that all too well. "There will never be a place like Blackwood again in the world we now live in," he said.

Membership

Membership