Picture this: You’re shopping for a new helmet. Some options employ carbon fiber shells. Others opt for polycarbonate or fiberglass. Whether it's safety certifications, EPS densities, or styling, each candidate is different from its rivals. Yet, all have one feature in common — a moisture-wicking liner.

And that one common feature could make them all illegal for sale in parts of the country in the future.

Nearly all modern motorcycle helmets utilize sweat-absorbing fabrics to enhance rider comfort. There’s just one problem. Nearly all manufacturers utilize per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) when producing these sweat-absorbing fabrics. And PFAS are not just found in helmet liners. They're also widely used in water-resistant and sweat-wicking riding gear and they're used in manufacturing motorcycle parts, including gaskets, O-rings, hoses, tubing, and semiconductors. Even the chrome-plating process requires PFAS chemicals.

That's why the Motorcycle Industry Council, the main industry association in the United States, is getting involved in state laws that are popping up and would ban the sale of consumer goods containing PFAS. The MIC warns that these state laws could change what personal protective equipment (PPE) is available in the United States.

What are PFAS and why are they in the legislative crosshairs?

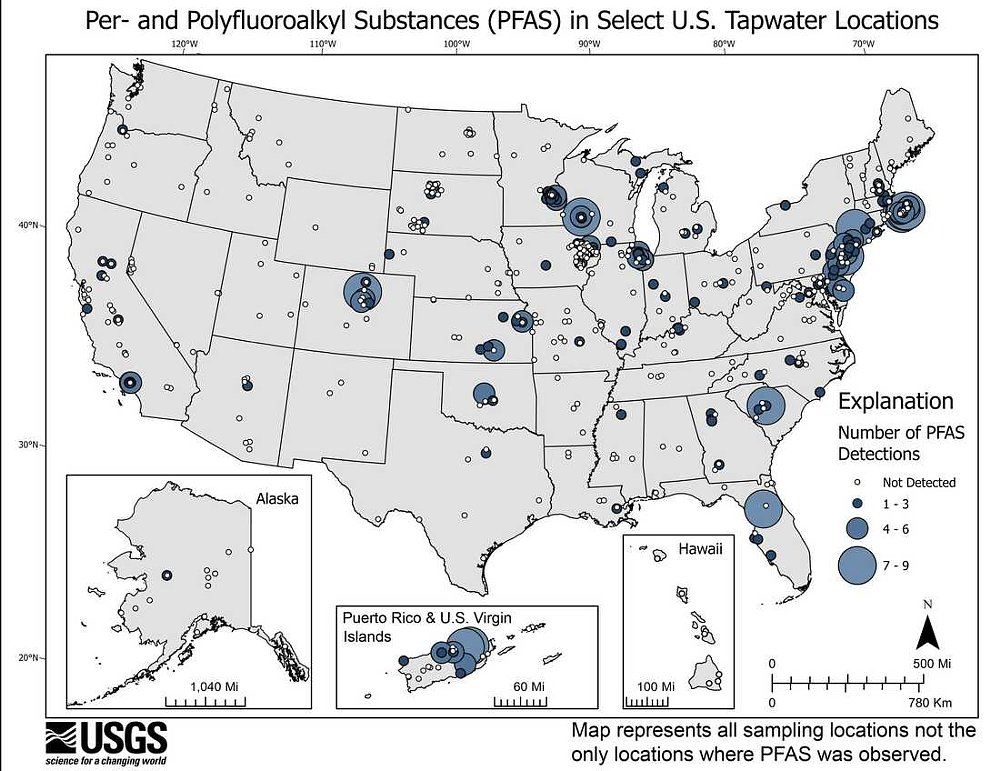

PFAS constitute a group of synthetic substances used in consumer and industrial goods since the 1940s. Sought after for their heat-, water-, and oil-resistant properties, PFAS are present in everything from household cleaning products to microwave popcorn bags to dental floss. Prominently located in and around manufacturing facilities, the chemicals often leach into local groundwater and soils, making their way into food and water supplies through production and waste flows. What’s worse, PFAS can also spread through the air, contaminating regions far from the original source.

Also known as “forever chemicals,” PFAS break down very slowly. That allows them to accumulate in the environment and in the tissues of humans and animals. Scientific studies have revealed that exposure to PFAS can increase cholesterol levels and the risk of obesity. At toxic levels, a person’s risk for prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers also rises. Side effects also include hormonal interference, which could result in reproductive effects in pregnant women and developmental issues in children.

It’s clear that PFAS chemicals pose a threat to personal and public health. But how do they impact the motorcycle industry?

Patchwork legislation

The dual problems are the prevalence of PFAS in motorcycle gear and parts and the patchwork nature of the legislative effort to address these chemicals. Individual states have begun working on laws that would ban the sale to consumers of products containing PFAS. The lack of a uniform approach would mean that it might be illegal to sell a water-resistant touring jacket to residents in Colorado or Maine and a helmet with a sweat-absorbing liner may classify as a 46-state item.

A Maine law initiated on January 1, 2023, now requires companies to register any PFAS-containing items sold in the state. Come January 1, 2030, Maine authorities will outright bar the sale of such products. California Assembly Bill No. 1817 is set to take effect on January 1, 2025, prohibiting the manufacture, distribution, and sale of PFAS-integrated textiles, including motorcycle gear. Massachusetts is also considering a crackdown on select industries starting in 2026, before implementing a full ban in 2030.

The United States isn’t alone in grappling with PFAS regulations. European Union member states are also weighing a proposition to phase out the harmful chemicals, but they’re taking a more collective approach to the process.

In January 2023, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) received a proposal to restrict PFAS from Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The five-nation committee’s plan calls for a broad ban on PFAS products with limited exceptions for specific sectors. The European Commission will decide the fate of the act in 2025 and, if enacted, the new law would establish an 18-month transition period beginning in 2026 or 2027.

After that initial stage, all 27 E.U. countries would prohibit the manufacturing and sale of products incorporating the substances. Only industries unable to shift to non-PFAS alternatives during the first phase will be granted a five-year derogation or 12-year derogation. An even smaller number will qualify for time-unlimited derogation (mostly in the medical field). Of course, the proposal has to clear several legislative hurdles before becoming law.

The European law may seem far-reaching to some, but it avoids the fragmented quality of American legislation.

It's possible, though, that the strictest laws will have effects beyond the U.S. states that pass them. Just as we have seen the rigorous emissions standards of the California Air Resources Board practically dictate the standard for all U.S. motorcycle lineups, PFAS legislation stands to reshape the motorcycle gear landscape.

I promise not to eat my motorcycle — or my rain suit

Motorcycle Industry Council (MIC) Senior Vice President of Government Relations Scott Schloegel testified in a hearing about the Maine legislation and he stressed the distinction between PFAS-containing products that come into contact with humans, such as riding gear, and those that do not, such as motorcycle parts. It's a distinction the Maine law does not make. There is precedent for this kind of argument succeeding. The Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 effectively banned the use of lead in products made for children, but after some lobbying, and children at demonstrations holding signs with messages such as "I promise not to eat my motorcycle," an exception was made for children's motorcycles and ATVs. It was clear that the risk of a child ingesting lead from a motorcycle was much less than the risk of that child trying to ride an adult-size vehicle.

Schloegel took the same approach to the PFAS issue.

"Most of our products that do actually contain PFAS... are internal parts, they're O-rings, they're the gaskets, they're hoses," Schloegel said. "These are not things that kids are out playing with or people are rubbing up against and having exposure."

Schloegel lauded a Colorado bill forbidding PFAS in youth products that exempted internal components “that would not come into direct contact with a child’s skin or mouth.” In Maine, he argued that it would be more effective to address ways to dispose of items with PFAS to prevent the chemicals from leaching into water supplies, instead of banning them all. Despite the MIC calling for exemptions on PFAS-reliant parts, the organization acknowledges that PFAS alternatives for O-rings, gaskets, fuel hoses, and chrome plating already exist. On the other hand, PFAS alternatives for gear have yet to be identified. As such, Schloegel is also asking Maine to push the compliance deadline out several years to accommodate manufacturers, suppliers, and retailers.

The MIC is not just working to slow down and adjust pending legislation, but is also urging MIC member companies to begin looking for ways to eliminate PFAS in the products they sell. Given the potential ill effects of exposure to PFAS through skin contact or ingestion, some products need to change and more laws are likely on the way. Shifting away from “forever chemicals” is both desirable and probably essential.

Membership

Membership