Earlier this week, the Piaggio Group released a lot of material from Moto Guzzi’s archive as part of the brand’s centenary celebration. You may think of Moto Guzzi as only V-twins, but in the early decades, when Carlo Guzzi led design and engineering, the company built everything from a moped to a V-8 racer. Here's a look at those early days.

The brand’s origin story begins in World War I, with a friendship between two pilots in the Italian naval air corps, Giorgio Parodi and Giovanni Ravelli, and their mechanic, Carlo Guzzi. The pilots were officers and gentlemen; Parodi was the scion of a rich family of shipowners in Genoa, and before the war Ravelli was a dashing pioneer aviator and motorcycle racer. Carlo Guzzi, meanwhile, had left school and apprenticed as a mechanic after the untimely death of his father.

Between sallies, the trio imagined life after the war as partners in a new motorcycle company. Guzzi thought he could build better motorcycles than were then available. Parodi would fund the venture. Ravelli would build the company’s reputation by winning races. Engineering, finance, marketing? Check, check, check.

Nevertheless, Giorgio Parodi and Carlo Guzzi stuck with their plan. Giorgio and one of his brothers incorporated Società Anonima Moto Guzzi in Genoa, where the family’s shipping business was based. Members of the Parodi family were the sole shareholders. Carlo Guzzi had no funds to invest, but struck a deal whereby he would earn a royalty on the sale of any motorcycle he designed. To honor the memory of their friend, Ravelli, they created a logo with an eagle on it that was similar to the air corps’ insignia.

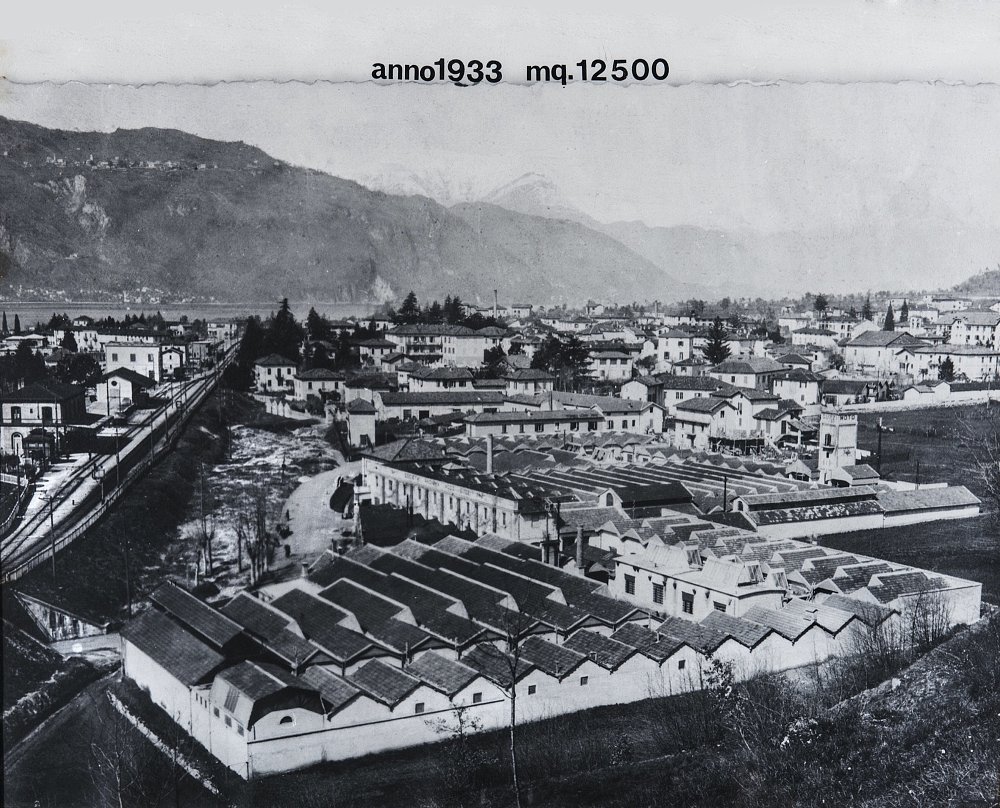

Although the company was incorporated in Genoa, it established a factory in the town of Mandello del Lario on Lake Como, in the mountains near the Swiss border. That might seem like an odd place for a motorcycle factory but the whole region of Lombardy was an engineering and fabrication hotbed, as Carlo Guzzi knew from serving his apprenticeship there before the war.

Moto Guzzi begins with a sturdy single

Carlo’s first design was a 500 cc laydown single with an external flywheel that resembled a bacon slicer. It was given the uninspired name Normale.

At the time, there were a lot of inlet-over-exhaust motors, with one overhead valve for induction and one side valve for exhaust. Guzzi flipped that arrangement, using the overhead valve for the exhaust. Otherwise, the Normale’s specs were, well, normal. But his design contributed to a low center of gravity which made for good handling, and motorcyclists noticed. Even today, vintage enthusiasts who ride old Guzzi singles rave about them.

Just a couple of years later, that basic design was adapted into Moto Guzzi’s first production racer, the C 2V (an acronym for Corsa 2 Valvole). It was hotly followed by a version with four overhead valves. Racing success brought attention to the brand. So did Carlo Guzzi’s brother, Giuseppe, who captured riders’ imaginations by riding the first full-suspension Moto Guzzi to the Arctic Circle in 1928.

That model was marketed as the Norge. The name was a tip of the hat to an even more intrepid Italian transportation endeavor in which Umberto Nobile used his semi-rigid airship, the original Norge, for the first verified trip to the North Pole and the first verified journey from Europe to North America across the Arctic.

Moto Guzzi continued to develop that laydown 500 for over 40 years. In 1939, the Alce (elk) was one of the first motorcycles specifically designed for what we’d now call adventure riding. It was intended for military use but was also sold to civilians.

Guzzi downsized it to 250 cc for the Egretta (egret) and Airone (heron) just before World War II. No new models were introduced during the war, of course; some of the factory was devoted to the manufacture of aircraft parts. Just after the war, new Astore (goshawk) and Falcone (falcon) models got telescopic forks.

Greater than the sum of its parts

The expression “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is nowhere more applicable than in motorcycles. The reason the company kept evolving the same basic design was that while it seemed bland and conservative on paper, it was remarkably effective on the road.

My friend Stephen Pate restores Vincents for a living, but is a self-described Guzzi fanatic in his personal life. He’s ridden every desirable vintage motorcycle, and recently told me, “Their exposed-flywheel designs are, pound for pound, the best motorcycles made. They’re simple, but the engineering — as transportation — was exceptional.”

“I had a 1937 GTS with a sidecar that I used as a daily driver when I lived in Chicago,” Pate recalled. “I also had a modern Monster, and there was always some little thing with the modern bike. But I knew at the end of the day that side-valve 500 was going to start and run. I’d occasionally forget to turn on the oil petcock, and soft-seize it on Lakeshore Drive, but if I just let it sit for a minute or two, I could kick it over and it would always get me where I was going, every time, without fail, always.”

The Falcone was the most numerous of the post-war 500s. By that time, production models had overhead valves and rear suspension.

“It’s capable of 80 miles an hour and easy to maintain,” Pate told me. But its handling set it apart. “It has a low center of gravity and it’s so light. The suspension, with springs under the motor. For what it was, it was exceptional.”

Commercial success funds racing excess

Over that period, Guzzi sold production-racing versions of the singles; the Gambalunga (long legs) version is now coveted. They were intended for the use of gentleman racers. As soon as the company was flush with cash, it also built radical Grand Prix racing motorcycles that bore little to no resemblance to production models.

One such bike was the “bicylindrica” 500, which the factory raced intermittently from the mid-1930s to 1951.

The twin was born of a period of intense innovation in Grand Prix racing. In the 1930s, Moto Guzzi’s factory 250 cc and 350 cc racers dominated those classes with adequate power, light weight, and good handling. (If you’ve been paying attention you’re detecting a recurring theme here.)

But in the premiere 500 cc class, multi-cylinder engines were now far more powerful than the factory’s four-valve single, which had changed little in a decade. Carlo Guzzi was infected with his rivals’ obsession with power, but was still trying to honor his betrothal to light weight. He grafted a second 250 cc cylinder onto his 250 racer, choosing an ungainly 120-degree V angle, to create the bicylindrica.

The bicylindrica’s greatest moment came in 1935, when Stanley Woods rode to victory in the Senior TT, the first Senior win for any Italian marque. But the machine’s heyday was cut short because Gilera and BMW factory 500s got superchargers that increased their output to about 80 horsepower.

Not that Carlo Guzzi was opposed to forced induction. He designed or supervised the design of several supercharged race bikes beginning in 1931 with an across-the-frame 500 four that was raced once, at Monza; none of the three machines entered finished the race. A supercharged version of its 250 was used to set numerous speed and endurance records but was only marginally successful as a road racer. In 1937, the company built a water-cooled and supercharged 500 twin, though I can find no record of a race history.

After those unsatisfying experiments with supercharging, the bicylindrica remained competitive on courses that put a premium on directional changes until WWII brought an end to Grands Prix in 1939.

The postwar era of extremes — from mopeds to a V-8

Luckily — and perhaps surprisingly — the Moto Guzzi factory survived the war largely unscathed.

Italy did not. The founders of Ducati, Piaggio (makers of the Vespa), Lambretta, and Carlo Guzzi realized that few Italians could afford motorcycles in the 250-500 cc range. What Italians needed were affordable mopeds and scooters.

By that time, Guzzi managed a large design and engineering staff. He tasked Antonio Micucci with creating the lightest, simplest, and most affordable Moto Guzzi ever. The result was the 65 cc, two-horsepower Motoleggera moped. The first new Moto Guzzi of the postwar period started coming off assembly lines in the spring of 1946.

Not to be outdone by Vespa and Lambretta, Moto Guzzi also introduced its take on a step-through with the Galetto (little rooster) in 1950. Compared to its rivals, Guzzi’s scooter had larger wheels and a more robust four-stroke motor. Guzzi sold about 75,000 of them; the model lasted well into the 1960s.

The factory anticipated a return to racing. So at the other end of cost and complexity, it developed a shaft-drive inline four with a roots blower. In a test at Monza, it was seconds a lap faster than the bicylindrica. It was raced successfully at Hockenheim, but like many other entrants, Moto Guzzi was caught out by a rule change.

In 1949, the informal promotion of Grands Prix and “Classics” was reorganized into an official World Championship recognized by the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme. One of the FIM’s first moves was to ban forced induction. The decision might have been a slap at the Axis powers; the German and Italian marques had relied on blowers but the English had largely eschewed them.

Guzzi tried to salvage the new four by replacing the blower with mechanical fuel injection, but it proved to be heavy, complex, and unreliable.

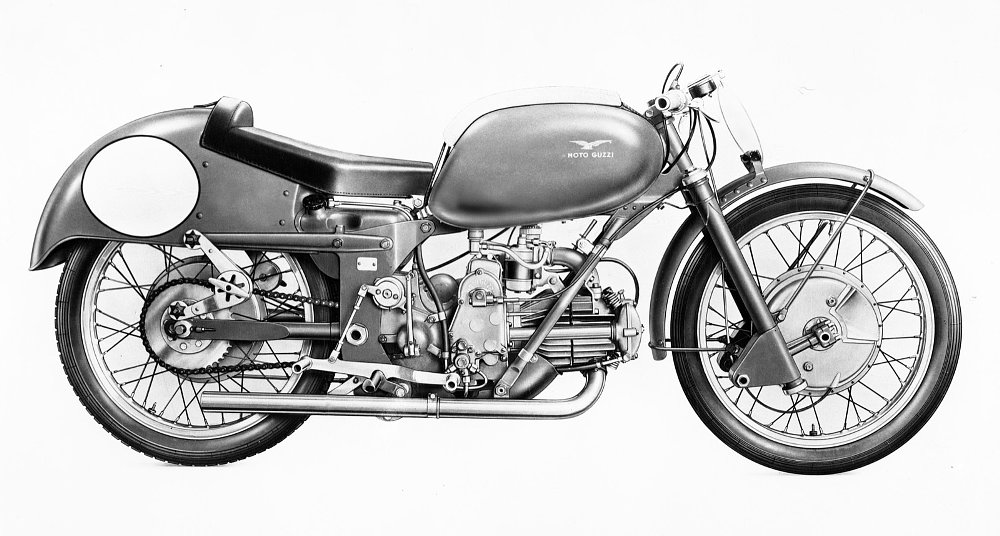

The ban gave the conventionally aspirated bicylindrica a brief second wind. Guzzi created a fuel tank that wrapped all the way around the steering head to form an integral front number plate and revised and minimized the already-innovative spine frame. According to Pate, Phil Vincent and Phil Irving openly admitted that the minimalist Moto Guzzi spine inspired the Vincent’s famous “frameless” design.

In its final form, the bicylindrica weighed less than 320 pounds. But it was still overmatched in the 500 cc class, first by the AJS Porcupine (another twin) and in 1950 by the Gilera four.

Searching for an advantage, Moto Guzzi became the first motorcycle company to build its own wind tunnel. Carlo Guzzi and his team (by then, Giulio Carcano was the lead engineer) quickly learned that “dustbin” fairings, which fully enclosed the front wheel, resulted in lower drag and higher speeds, but that was hardly knowledge they could conceal. By the mid-1950s, the glorious dustbins were ubiquitous.

Superior aerodynamics extended the competitive lives of Moto Guzzi’s 250 and 350 cc GP bikes. The singles were light and hooked up well coming off corners. But in the premiere 500 cc class, Carcano knew that to run with the Gilera four, Moto Guzzi needed a new multi-cylinder motor of its own. If Gilera’s four was good, a six would be better but wider, and one thing he’d learned with all that wind tunnel time was that width meant drag. He realized that a V-8 would be no wider than a four and have superior cylinder filling. Testament to Carcano’s genius and Moto Guzzi’s fabrication capabilities: It went from idea to running prototype in about five months.

The V-8 became the most famous Moto Guzzi engine, but it’s famous for audacity, not results. Carcano had obviously absorbed his mentor Guzzi’s obsession with weight. To reduce the weight of fasteners, iron cylinder liners were threaded into the heads. The cases were magnesium, of course, as were the eight tiny carb bodies. There’s a famous photo of rider Bill Lomas holding the motor in his arms.

The machine saw limited action in 1955, but its first full World Championship was 1956. There were six rounds that year; the Guzzi V-8 tallied six DNFs. Undaunted, Carcano continued to develop it in search of reliability. In the run-up to the 1957 World Championship, the V-8 won a couple of non-championship races.

At its best, the V-8 made 80 horsepower at 12,000 rpm. It posted the fastest lap in the Belgian GP at Spa, where it went through the speed traps at 178 mph. Those were staggering numbers — at least 10 years ahead of their time in the 500 class — but it never won a World Championship race.

Looking back on the famous machine’s short history, Cycle World magazine writer Kevin Cameron speculated that given another season or two, it may have come good — although the V-8’s high speed, rearward weight bias, hard tires, and a dustbin fairing combined to produce weaves and wobbles that terrified even the bravest riders.

One of the few surviving V-8s is displayed at the Moto Guzzi museum in Mandello del Lario (shown in the top photo). It’s a shrine to the Guzzisti; a monument to glorious failure. Meanwhile, those Moto Guzzi singles — rugged, reliable, and built in huge numbers — just roll on.

I was curious about parts support, so I called Curtis Harper; he’s the second generation at Harper’s Moto Guzzi, which is the largest North American repository of post-1967 NOS Guzzi parts. He reassured me that there’s a cottage industry of European shops like Cavazzutti in Switzerland and Guzzi Retro in Italy devoted to the singles.

“Once you get them running, they’ll keep running forever,” he told me. “They don’t make enough power to hurt themselves.”

Carlo Guzzi’s greatest design outlived him. Falcones were still coming off the line in Mandello del Lario when he died in 1964.

Guzzi’s foremost acolyte, Giulio Carcano, retired in 1966 after 30 years with the company. But before he left, he designed a V-twin with the motor mounted across the frame and shaft drive. It was intended for use by Italian police, but ended up having a lifespan even longer than Carlo Guzzi’s laydown single.

That’s a whole ’nother story.

Membership

Membership