Pirelli’s global headquarters campus occupies an entire city block in Milan’s Bicocca neighborhood. It used to be the site of a big Pirelli tire factory, but the old factory became surplus to Pirelli’s needs after the Italian company acquired Metzeler. At that point, most European production was consolidated in a factory in Breuberg, Germany.

Since acquiring Metzeler and moving production to Breuberg, Pirelli is almost part-German, but the HQ culture’s still Italian, so our tour began with espressos on an upper floor, where the marketing and communications group has its own tiny café. They explained that the Pirelli and Metzeler motorcycle brands operate largely independently in terms of marketing, with different specialties and postioning, although the testing operations we were about to see are shared.

At the conclusion of those formalities, we met with Luca Bruschelli. He’s Pirelli’s head of motorcycle tire development, and one of the many engineers the company recruited from Politecnico di Milano. (Basically, Milan’s local engineering school is Italy’s MIT; it’s rated among the world’s top 25 engineering schools.)

Luca walked us out of the office tower and across a courtyard to another modern building, which houses the Pirelli Tire Research Center. This transit involved several rather comical incidents involving our security badges and various automatic gates, but eventually we made it into the Research Center, where we took an elevator down into a cavernous sub-basement straight out of James Bond, full of mysterious pieces of equipment, computer screens flashing cryptic data, and cages where tires are tortured, occasionally past the breaking point.

“This is ‘Minus 2’,” Luca told us. “There is also Minus 3 and Minus 4.”

We began our tour in the "static testing" area, walking past racks of everything from Formula 1 and World Superbike tires to what looked like relatively ordinary tires for passenger cars and heavy trucks. Mounting and balancing machines were ready to put tires on hundreds of specialized test rims. Although I saw a few O.Z. magnesium F1 wheels, most of the test rims are aluminum or steel, and visibly heavier than normal wheels; they had different bolt patterns, too, depending on what test beds they’re mounted to.

Luca guided us past a whole complex of soundproof rooms containing machines resembling chassis dynos, which are used for things like wear testing. Each room is individually climate-controlled. Although most tests take place at a constant 25 degrees Celsius (77 degrees F), Pirelli can test tires at ambient temperatures from above 70 degrees Celsius to -40 (158 to -40 F). Tires destined for the African market are tested at an ambient 38 degrees Celsius (100 F), for example.

Luca pointed out the one-inch gap, like a tiny moat, around each of those rooms. Each room extends down to the "Minus 3" basement where it floats on a vibration-damping "seismic" foundation. The whole idea is that each chamber is completely isolated from every other one, so that no vibration from one test can compromise the results of a different test taking place nearby.

We saw a lot of tires that looked, at first glance, like go-kart slicks. It turns out that when Pirelli took on the role of sole supplier for Formula 1, the company not only had to make the full-sized tires the cars race on, but also scaled-down tires for use in wind tunnel testing. Those tires not only have to be proportioned like F1 tires — that would be too easy — but they also have to deflect to scale, under scaled-down loads.

Although other tire makers use electronic scales to map pressure across the contact patch at full scale, Luca told us that no commercial sensor produced data of the required granularity at the scaled-down levels of downforce they needed to simulate. So, Pirelli built a device that looks like the bottom of a photocopier mated to the top of a hydraulic ram, which presses the tire onto a transparent plate, a sheet of glass capable of sustaining loads of about a ton. Pirelli’s machine laser-scans the contact patch from below, and uses optical interference to map pressures more accurately and at higher resolution, to give engineers a better idea of how the tire transmits pressure to the track. Now that they’ve built it for F1, they use it to study the contact patch of other new tires under development. The ram that presses the tires onto the plate can push a motorcycle tire onto it at an angle, too, to map contact patch pressure under side loads.

Many dynamic tire tests involve turning the tires with huge metal cylinders, which provide useful data but don’t perfectly mimic the contact patch and carcass deformation on a normal road. So, MTS Systems Corp (based in Minnesota) built Pirelli a special machine — imagine a giant, upside-down belt sander — that makes for a more accurate simulation of a tire running on a generally flat surface. The machine can constantly vary slip angle, camber, pressure, etc., and technicians can use it to simulate any vehicle on any paved road or track. When we were there, several engineers were watching an infra-red video feed of a tire being tested, to see where heat built up in the carcass. As was the case with a lot of the test beds, that one was robotically controlled and the engineers watched through thick laminated windows.

Nearby, other techs used a laser to print an experimental tread pattern on a slick base tire. After the desired pattern was precisely printed, the tire moved to a room where a small team of guys painstakingly hand cut the prototypes, with an array of special cutting heads. They looked like Renaissance sculptors, and they go through nearly as difficult an apprenticeship: After a year of training and practice, supervisors give them a pass only after grading their hand-cut patterns with micrometers.

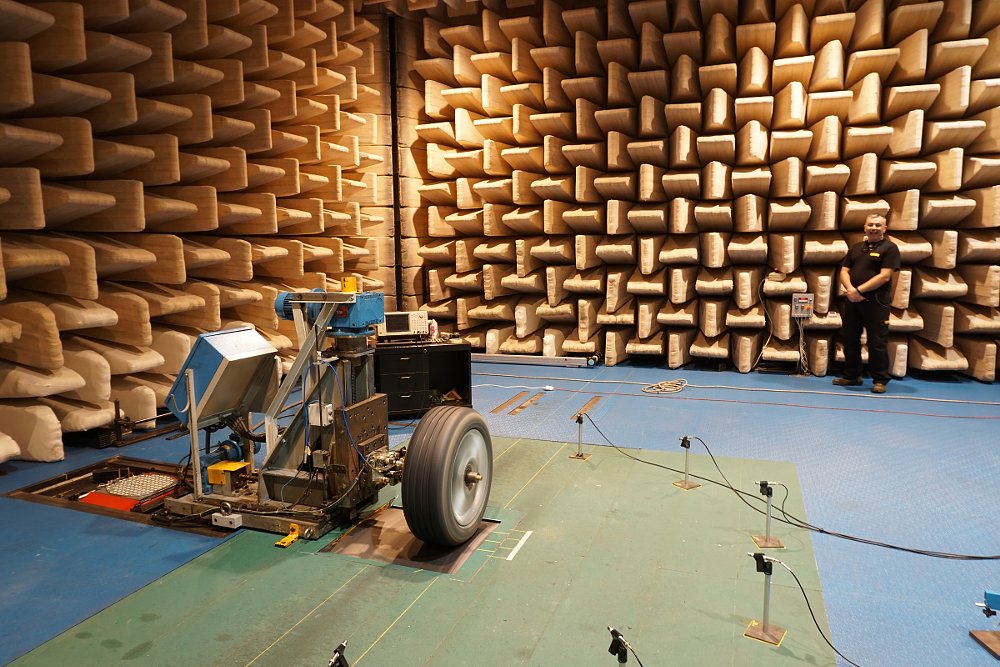

The most weirdly fascinating test we saw was conducted inside a huge anechoic chamber with a door at least five feet thick. A tire turned on another one of those huge steel drums, surrounded by an array of microphones. It looked like a conceptual art project, but tough Euro IV sound regulations have made rolling noise a significant concern for tire makers.

A typically Italian lunch break from testing

When we were setting up our visit, Laura Venatti, from Pirelli’s PR group, told us, “Then, you’ll go for lunch with Piero Misani in the castle.” I was excited to chat with Misani, because he’s in charge of all Pirelli’s motorcycle R&D — he’s the kind of guy I’ll have lunch with any time! I figured ‘The Castle’ was the name of some nearby trattoria.

Not quite. As it turns out, there’s a perfectly preserved 15th century hunting lodge inside the Pirelli perimeter. Most days, our private dining room experience would have been way off limits to the likes of a mere motorcycle journalist. It’s where Pirelli’s CEO holds lunch meetings. Luckily, on the day of our visit, he was traveling, so we became the lucky guests.

Pirelli’s executive chefs delivered a delicious meal of basil risotto with gamberi, and bresaola with arugula. I got the feeling the chefs carefully calibrated a menu light enough that it would not put several high value engineers out of commission for the afternoon. White wine was available but not pressed on them. (Since all I had to do the rest of the day was get flown down to Sicily, I had a glass. Turning it down would’ve hurt the sommelier’s feelings and I’m far too considerate for that.)

Piero and Luca, and a few other engineers and marketing types joined us for a freewheeling conversation. Misani began by telling us a little bit of the history of the Pirelli headquarters, explaining that the neighborhood was heavily industrial until the 1980s. Back then, his office was directly across the street, in a building that has since been taken over by the Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca. Conveniently, that building now houses the university’s Materials Sciences department.

“We do a lot of work with them in the field of nanomaterials, nanotechnology, and industrial processes,” Piero said. “It’s convenient because I only have to walk 50 meters to attend meetings!”

While we were on the topic of universities, I asked Piero where students who wanted to study motorcycle engineering could go. “Your only option is Padova, where Prof. Cossalter is doing work on motorcycle dynamics,” he said.

“For tires it’s even worse! It’s a specific know-how,” Misani continued. “Typically when you go to university, you study small deformations; with aluminum or steel, your epsilon is three or four percent, but with tires we have large deformations. So everything that has to do with tires, at university, is neglected. For tires, there’s no place to go and learn.”

There’s no bat wing in the compounds, really. (Or if there is, they won’t admit it.) Misani told me that Michelin and Bridgestone are vertically integrated and make their own polymers, while Pirelli prefers to work with two key polymer suppliers, based in Japan. “They have to live off polymers, and they are the best at it,” he said. “They dream about them, and are at the cutting edge.” The only downside to having outside suppliers is that after a couple of years, those suppliers often want to sell the same polymers to other companies. By then, Pirelli will have moved on anyway.

Even the simplest compounds now involve blends of about 15 different polymers and carbon black, which is basically a stiffener and reinforcing agent. It works to reinforce the soft and elastic polymers the same way sand mixes with cement to toughen concrete.

Misani told me that carbon black never used to really chemically bond with the polymers, but that in recent years, there’s been a revolution in compounding. Most modern compounds now include polymers, carbon black, and silica — which improves wet grip by chemically adhering to wet surfaces. The challenge for compounders has been to bond silica to the polymers, which is the role of additives like silane. What used to be a fairly simple mechanical process of mixing the components, however, is now a precisely controlled chemical reaction.

Misani told us these manufacturing processes are the biggest thing in motorcycle tires since radial belts came in, in the late 1980s. It’s not the ingredients, it’s the way the ingredients are processed, that matters most.

“For Italians, this is easy to understand because we’re crazy about food,” Misani explained. “I can give you the recipe for a good pizza, but with the same ingredients you can make a crust that’s thin or thick. It’s the same with tires, you can have one that’s stiff or soft, with better or worse wet grip, with all the same ingredients, depending on the process.” In the case of tire compounds, the process determines the nature of the cross-links — which are usually sulfur bonds — between the long polymer chains.

That compounding research is still done experimentally. Pirelli’s in the early stages of developing models that will allow the company to predict outcomes. But for now, because the chemistry’s difficult to fully understand and predict, the work we saw underway — the testing of experimental tires — is vitally important.

Our lunch was a short one by Italian standards, about an hour and a half, and a particularly enjoyable one — because of the food of course, but also because the engineers didn’t talk down to me (which can be a bit of a problem in the life of a motojournalist.)

I left with two overriding impressions. The small one was that being World Superbike’s official tire supplier is a business proposition for Pirelli — it’s a profit center — but that they’re really passionate about Metzeler’s involvement with races like the Isle of Man TT. That was the only racing anyone really wanted to talk about.

The bigger impression is that Pirelli is basically an unaccredited post-graduate school. The company recruits engineers (almost everyone at the table was a graduate of Politecnico di Milano, even the marketing guys!). But as Misani had explained, no engineering school teaches you how to make tires. So Pirelli invests years of training in these technical employees, who repay the company with a loyalty that could almost be called devotion.

After lunch, we turned those guys loose to go back to their jobs creating new tires. Mary and I hopped on a plane to Sicily, where Pirelli’s "outdoor testing" is based. Because, after all, you can test tires in the lab all you want, but what really matters is, how they work on motorcycles. Pirelli’s outdoor testing crew includes over a dozen full-time testers who rack up something north of a million kilometers a year, on- and off-road, on public roads and closed circuits.

Talk about a dream job for a motorcyclist. But that’s a story for another day...

Membership

Membership