For some motorcyclists, riding is about answering questions like "Can I make it up that hill?" "How fast can I take that corner?" Or "How far can I lean before the hard parts scrape?"

For others, the question is "How far can I ride in a day?"

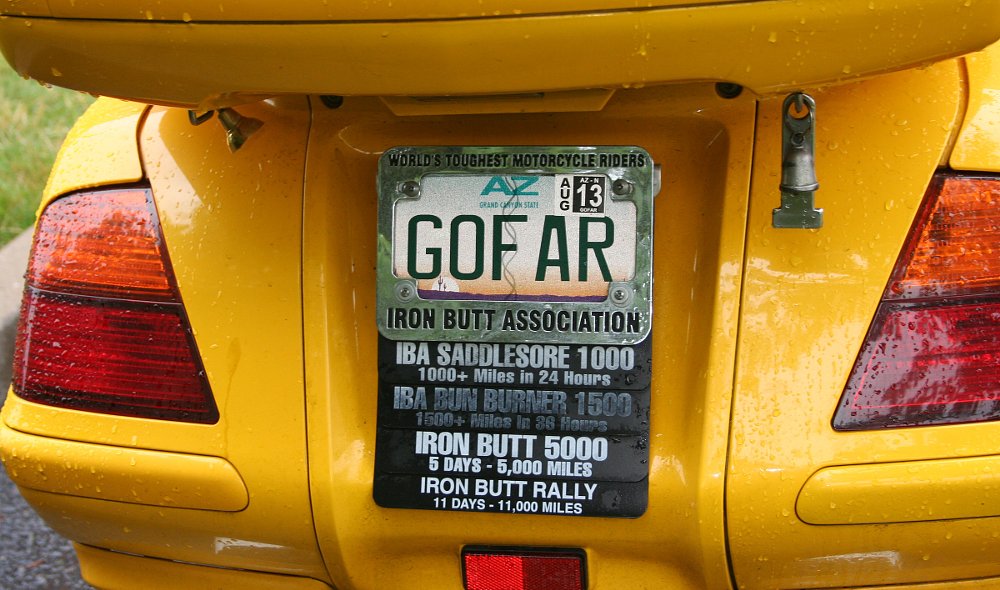

If it seems like a frivolous concern to you, it isn’t to the more than 75,000 riders worldwide who have answered it by riding a SaddleSore 1000. Also known as the SS1K, it’s the shortest ride certified by the Iron Butt Association, the home base for the subset of riders for whom the torturous Iron Butt Rally — in which riders can cover 11,000 miles in 11 days — is the ultimate test of riding skills and personal endurance.

The world of long-distance riding defies simple explanation, but a good start is the list of long-distance rides the IBA certifies. You'll find more oddball challenges than you can shake a wrench at, combining miles traveled, maximum time to complete the ride, the type of bike, and the time of year, and special rides tailored to at least 10 foreign countries. The most popular one, and the easiest one to complete to earn membership in the IBA, is the SaddleSore 1000, which requires you to ride at least 1,000 miles in 24 hours or less.

Before you cringe at the idea of riding flat-out, chin on the tank, for 24 hours, outrunning cops and blowing by slower traffic like haybales on the side of the track, do the math: 1,000 miles in 24 hours is a 42 mph average. Anyone on a reliable bike with decent range can leave before sunup, ride the miles on the interstate, stop only for gas and a quick meal, and be home in time to catch the 11 o’clock news. In fact, the calculus of long-distance riding favors a conservative and steady pace over a balls-out sprint. High speed equals poor gas mileage, thus more frequent fuel stops. Fatigue is a factor, too. Tired riders make mistakes, and you can’t finish the ride in the back of an ambulance. (Well, you can, but you won’t get your finisher’s certificate.) Then there’s the ever-present risk of lengthy roadside conversations with officers of the law about your cavalier attitude toward speed limits. All work against the goal of covering the miles safely, efficiently, and on time.

Those who have completed an SS1K — a remarkably diverse gang of sometimes mildly unstable characters that includes me — will tell you it’s not as daunting an undertaking as it sounds. Still, there are ways you can prep your bike and yourself to tilt the odds of success in your favor.

How to prepare for a Saddlesore 1000

Start by making sure your motorcycle is ready. In addition to the usual checks — tire pressure and tread depth, oil and coolant levels, chain tension and lubrication — fix any nagging problems that have been bugging you lately. A hard or misshaped seat, a stiff clutch cable or a handlebar bend that’s not quite right might be minor annoyances on your commute or a weekend ride, but after eight or 10 straight hours they can sap your mental energy and beat your body down. Veteran long-distance riders say, “Make your bike the most comfortable place to sit that you own.” Add a windscreen, heated grips or a seat pad to help those 24 hours or less fly by.

Do the same with your riding gear. A slight pressure point inside your helmet becomes a jackhammer after several hours, and those raised seams in your gloves cut into your hands like knives. Depending on the time of year, wear vented gear or water-resistant or waterproof outer layers (changing into and out of a separate rainsuit takes time). Whatever the season, bring a heated vest or a thermal jacket liner. Many riders do their SS1K in the summer to maximize the daylight during the ride, but after hours of riding in extreme heat even mild nighttime temperatures can chill you to the bone.

Other things are handy but not absolutely necessary, such as a GPS or a smartphone with a GPS app. In addition to keeping you on your chosen route, a GPS gives you real-time average speeds and time-to-destination information to help you stay on schedule. And finally, since you already know how to perform basic maintenance tasks like checking the oil and tires, and lubing and tensioning the drive chain (you do, don’t you?), bring along a complete toolkit, a tire repair kit, and a 12-volt air compressor to handle roadside emergencies. Throw in a road flare or a reflective triangle in case of a breakdown after dark, and make sure your cell phone is charged and your towing-service membership is paid up.

If, like me, you believe caffeine is second only to air as a necessity of life, grit your teeth and give it up for a week before your SS1K. Coffee and energy drinks might get you through your day, but on a long ride, after the buzz wears off you’ll crash hard — with luck, only metaphorically. Constantly stopping to tank up on liquid enthusiasm and again later to let out the residue reduces your time on the road, and as LD riders also say, “If you’re not twisting the throttle, grabbing a snack, hitting the rest room, or filling the tank, you’re wasting time.”

Practice getting your gas stops down to no more than three minutes from sidestand down to sidestand up, keep your gas card in an outside pocket where it’s easy to get to, and don’t forget to get timed and dated receipts — they’re the basis of the proof that you did the miles in the specified time. You'll also need a camera to take photos of your receipts and your odometer.

Speaking of receipts, be sure to read the rules carefully at the Saddlesore 1000 web page before you start, including the alternate rules for using an eyewitness instead of a starting receipt. If you finish the ride but lose your receipts or don't get all the ones you need, you'll still have the personal satisfaction — but you won't get the Iron Butt certification.

Maybe the most important thing to know before you start your SS1K is that where and when you do the ride is entirely up to you. The only fee involved is paid when you submit your documentation, so if it all goes wrong during your attempt and you can’t finish the ride in 24 hours, there's no reason to kill yourself trying. Just throw in the shop towel and try again another time.

My Saddlesore 1000

I did my SaddleSore almost 21 years ago and I still remember the weeks of anxiety leading up to it. What should I take with me? What if something goes wrong? I stuffed the saddlebags of the borrowed Harley-Davidson Heritage Softail I was riding with tools and extra clothes and set out one morning in July before dawn. Rules were a bit different back then, so I got my starting documentation signed by a sleepy pump jockey in Coos Bay, Oregon, rode east to I-5, took the interstate north to Portland, went east again to LaGrande, and then turned around and retraced my route.

In the second hour of the ride, it started raining — hard, this being Oregon — and I seriously thought about changing my route to avoid it. Then I remembered an LD rider adage: Plan the ride, ride the plan. This was no time to improvise, so I soldiered on, ready to be miserable. I was wearing Aerostich gear so the rain never got to me, and in fact it stopped for good an hour later. I treated every gas stop like a pit stop in a race, tucked each precious gas receipt in my pocket as if it were an undiscovered Shakespeare play — without the required documentation, I was just out for a long joyride — and finally relaxed into the ride about 400 miles from home. I returned to Coos Bay early the next morning, having ridden 1,073 miles in about 22 hours, including a rest break, a quick lunch, and a 30-minute diagnostic session in a Subway parking lot to find out why my heated vest’s controller died.

Riding the interstate from point to point or in a large loop is the easiest way to knock off the miles. Some riders prefer a more challenging route, but the greater the challenge the greater the odds against success. I advise prospective SaddleSore riders to take the easy route on their first try; they can always amp up the degree of difficulty on their next one.

The first SS1K is a learning experience. More than anything, it teaches you how to juggle time, distance, speed and the conditions. These skills are useful even if you never do another Iron Butt Association certificate ride, and they give you a confidence in yourself and your riding that you just can’t get on a Sunday afternoon ride to Starbucks.

Fair warning, though — you might also be tempted to try some of the more difficult rides the IBA certifies. I have many friends who have gone down that rabbit hole, and for most of them there was no coming back.

Membership

Membership