International travel is one of my favorite pastimes. I always find the cuisines and customs of other cultures fascinating. When reflecting on those visits, the rules of the road rarely come to mind. I can’t say the same when I reflect on my last 11 weeks in Japan.

When I arrived in Tokyo in early August, I wasn’t a complete virgin to Japanese roads. I’d previously ridden in the Tochigi countryside while testing Bosch’s new Advanced Rider Assistance System (ARAS). But like most press launch experiences, I simply followed a lead rider through rural, mountainous roads. I wasn’t afforded such luxuries during this trip.

Riding in a different country presents its own novelties. Some countries drive on the left side of the road. Most road signs are written in the native tongue, not English. Both are true of Japan. To add to my unease, I didn’t know Jingu-Dori Street from National Route 1, or how to connect the two. I didn’t just need to navigate a sprawling city. I needed to navigate different traffic rules. So that’s where I started.

Sign language

Japanese roads aren’t all that different from U.S. roads. They’re paved with asphalt (impeccably so, in fact). There are stop signs and traffic lights at intersections. Sure, they drive on the wrong side, ahem, the left side of the road, but that’s an easy habit to pick up by following the pack. What takes time to adjust to are the rules of the road.

For instance, unprotected right turns are largely legal in the United States, but their equivalent in Japan, unprotected left turns, are illegal. Motorists can only perform left turns at intersections under the protection of a green arrow. Making a right turn across oncoming traffic requires even more vigilance.

Many of Tokyo’s traffic signals house lights for several directions of travel. That frequently gave me cause for pause, especially when performing a right turn. Some intersections allow motorists to yield to oncoming traffic. In those instances, the vehicle moves to a designated turn lane in the middle of the intersection. When a safe break in traffic develops, the motorist then executes the maneuver.

In other cases, right turns are only permitted under a green right arrow. To help reiterate that point, the upper right signal remains illuminated in red (see image above). Oftentimes, the green straight and left arrows will turn red before the right arrow turns green, giving you the right of way. Understanding those different cues isn’t just key to remaining safe on the roads; it’s key to avoiding the ire of locals.

Beyond the road signs, Japan also implements a series of driving stickers that distinguish novice drivers, senior drivers, the hearing impaired, and handicapped drivers from standard drivers. These markers helped in several ways. Not only did I give these drivers more grace, but I also overtook them in a calm, measured manner. In that way, the system considers all parties on the road, and it’s something I wish more countries adopted, including the United States.

Take its toll

When it comes to personal vehicles, Japan’s Expressways are the fastest way to travel. That kind of convenience comes with a price tag, however. Now, this Californian is familiar with tolls on roads, bridges, tunnels, and express lanes. The residents of 37 other states are, too. Odds are, readers have paid a toll on U.S. roads at some point or another. The difference between our tolls and Japan’s is the sheer number of them.

Tokyo and the Twin Ring Motegi are separated, in part, by 70 miles of expressway. Over that span, I encountered four different toll booths and paid nearly $25 in toll fees. The same held true on my return trip to the city. Unless you’re content to stick to surface streets — incurring hours of additional travel time in the process — there’s no circumventing those expressways and their associated charges. Virtually unavoidable they may be, but those tolls don’t have to be inconvenient.

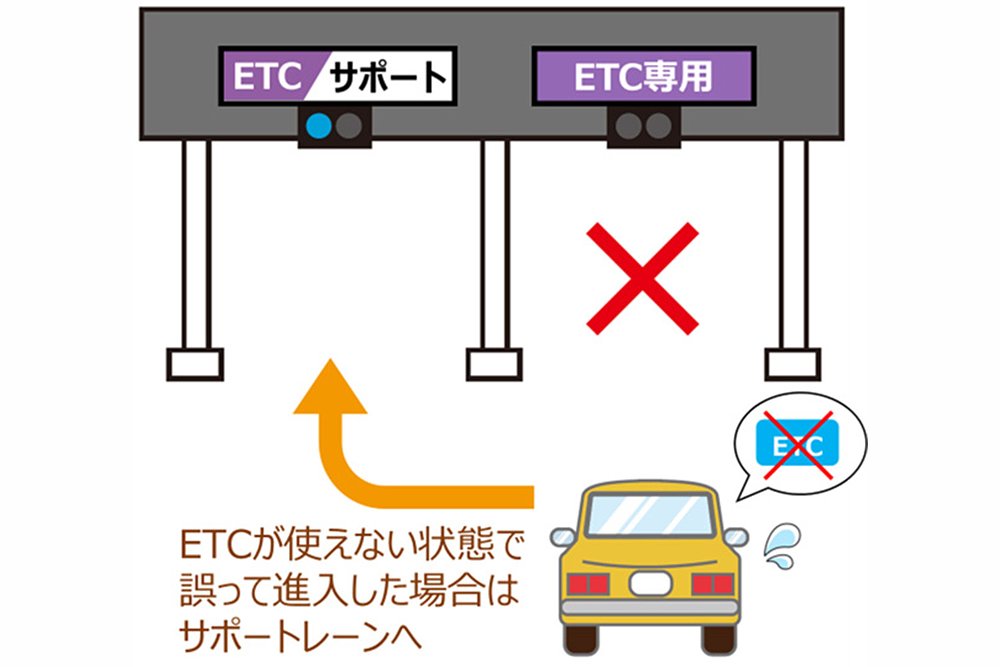

Japan’s Electronic Toll Collection (ETC) is an automatic toll payment system that enables motorists to pass through toll gates without fully stopping. It cuts down on both toll booth traffic and drive times. On the flip side, ETC requires the owner to integrate an onboard card reader into the vehicle’s electrical system. In my experience, that time investment is worth the time savings later. I learned that lesson first-hand.

Both the Harley-Davidson X350 and Honda GB350 I tested in Japan came with an ETC card reader. I can’t say the same for the XSR900 GP Yamaha loaned me. That one exclusion forced me to stop at each toll booth, which typically resulted in a three-to-five-minute delay. That seems insignificant if your route only includes one checkpoint, but come across four, and the holdups quickly add up.

In sum, if you plan to ride a motorcycle during a future trip to Japan, you should also plan on finding an ETC-equipped rental. I frequented Rental819, but only certain locations offered ETC cards. That’s one detail I checked before booking any bike. The additional research was worth it in the end. Plus, finding appropriate parking spots for that rented bike will require just as much research.

Park it

On-street parking isn’t strictly outlawed in Tokyo, but it’s close. That’s especially true overnight, when even commercial vehicles vacate the limited on-street spots. While off-street parking is plentiful, motorcycles must park in designated lots, which are less abundant. Finding those locations can present challenges, too.

If I didn’t happen to come across motorcycle parking while riding, which was often the case, I needed to pull off the road and check Google Maps. Locating a suitable parking spot was just the first step, though. Some parking lots accept credit cards. Others only take cash and coins. Most don’t issue change, either, requiring customers to pay fares in exact amounts or risk losing additional money. If you aren’t carrying one of the accepted forms of payment, the search starts all over again. Good. Grief.

The lesson to be learned here is to carry a billfold and/or a coin purse. It doesn’t hurt to look up parking spots around your destination before departing, either. More than once, I learned this lesson the hard way. Ultimately, the parking rigamarole is surmountable. Experience and routine go a long way in this area. At the same time, the parking situation often deterred me from exploring new neighborhoods or enjoying a spontaneous joy ride. That’s why riding in Tokyo felt more like business than pleasure. It wasn’t the only reason, either.

Peace out

The biker wave. I doubt I have to explain the concept to this audience, but simply put, it’s the exchange of friendly gestures between passing motorcyclists. Dropping the two-fingered peace sign or flashing a brief wave of the hand will suffice. It’s a show of solidarity. It’s a sign of camaraderie. It’s also something I rarely received in Japan.

My wife often compares motorcyclists to dogs. (It’s not for any of their more unflattering behaviors.) That’s because whenever the sound of a loud exhaust echoes down our street, my ears perk up and I rush to the window, just like a dog when a fellow canine passes by. I’m just as engrossed when another bike passes me on the street. What bike are they riding? What helmet is that? Are those chaps?

I rarely received that same level of attention from other motorcyclists in Japan. In most cases, passing riders hardly acknowledge me at all. It wasn’t just in Tokyo. I had the same experience in the mountains, where cars are scarce and bikes are a dime a dozen. With time, and against my own instincts, I learned to ignore my fellow motorcyclists and scooterists. So much so that I was startled when a random rider flashed a peace sign to me. I almost forgot how to respond in kind.

All that’s not to say that Japanese riders are against the biker wave. I just know not to expect it when I ride in the country sometime down the line.

Pedestrians first

Tokyo is a pedestrian-friendly city. It’s easy to see why. The streets are narrow, keeping traffic speeds low. Metal or concrete barriers separate the road from the sidewalk, protecting pedestrians from passing cars. The interactions between motorists and pedestrians only reinforce that idea.

Walking around my neighborhood in Los Angeles, I’m often confronted by one question when I arrive at a crosswalk at the same time as a motorist: Will they gun it through the intersection or allow me to pass (I have right of way, of course)? That was never a question in Tokyo. Even if the pedestrian is at the other end of the street, the vast majority of drivers yield to them. It’s a habit that I was happy to adopt as a motorcyclist.

If I learned anything during my time in Japan, it’s that the unspoken rules carry just as much weight as the written ones. It’s not just the laws you observe, it’s the courtesy you show others, as well. The respect I paid other motorists and pedestrians was often acknowledged with a nod or half-bow. If I could bring anything back to the U.S. roadways from Japan, it would be that.

Common courtesy

It’s clear as day. Japan’s rules of the road differ from those of the United States. Some are subtle. Others are substantial. Some I embraced. Others I dreaded. For every novice driver sticker I applauded, there was a toll I detested. Riding in any country presents its own challenges and rewards. That goes for both Japan and the United States. If anything, riding in Japan didn’t illustrate that its traffic laws are superior. It simply illustrated that common courtesy is always an option.

Group harmony is a priority in Japan. That much was evident on its roads. I seldom heard blaring car horns. Fits of road rage were non-existent. I never even crossed the scene of a crash. Anecdotal as that evidence may be, collision data only supports my observations. If I had the power to implement similar habits here in the States, I would. Here’s the thing: I do. It starts with me.

I can give more grace to other motorists, regardless of their experience, age, or ability. I can reassure more pedestrians at crosswalks. And I can thank the ghost of Dwight D. Eisenhower for every mile of free highway I ride. Japan showed me that U.S. roads have room to improve, but it also showed me what I should be grateful for. Such are the lessons learned from international travel.

Membership

Membership