Back in 2018, Ducati engineers told me that they expected to bring Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC) to market for the 2020 model year. It took a while longer, either because it was harder than they thought, or because, as you may have heard, there’s a pandemic.

Last month, Bologna finally announced that the ACC it had developed with Bosch would be available on its new flagship, the Multistrada V4S. Barely a week later, BMW announced that it, too, would make a Bosch ACC system available on the 2021 R 1250 RT. The two announcements came close enough together that I’ll call it a tie for “World’s First” bragging rights.

Ducati

- Francesco Zucchelli, Electronic Systems Supervisor (Bologna)

- Davide Previtera, Vehicle Project Manager (Bologna)

- Phil Read Jr., North American marketing director (Mountain View, CA)

BMW Motorrad

- Reiner Fings, Director of Product Development for R-series/boxer twins (Munich)

In addition to those interviews, I also found useful information in an informative BMW #RideAndTalk video podcast.

The companies have announced ACC on three models. According to Phil Read, Jr., ACC will be standard on all Multistrada V4 S and V4 S Sport models in North America. (U.S. customers will be able to special order a V4 S without it.)

Over at BMW, ACC will be available, but not standard equipment, on the 2021 R 1250 RT. In the U.S. market, you should expect ACC to be part of a premium package that will include other features. Reiner Fings told me that in Germany the ACC option costs an additional €500.

Tapping their big brothers and Robert Bosch GmbH

Ducati is owned by Audi, and Previtera told me that Audi had been a big help in the early stages, although there were many challenges that were unique to motorcycles. Markus Hamm, Motorrad’s ACC Project Leader, spent years working in BMW’s automotive division on ABS and TC projects, so Motorrad also had an automotive base to start from.

Both companies relied on Bosch as a Tier 1 hardware supplier, and in fact both systems use a radar sensor that Bosch also supplies for use on automobiles. In a followup e-mail, a BMW representative pointed out that the sensor had to go through additional testing to prove that it could handle a motorcycle’s vibration and electromagnetic interference.

Considering that both companies started from a similar knowledge base and used the same supplier, it’s not surprising that their solutions are similar, but they are not identical. The most obvious difference between the two companies’ approaches is that Ducati’s ACC is paired with a rear-facing radar that also provides a blind-spot warning system. Fings told me that BMW was considering adding blind-spot monitoring in the future. (BMW has already offered that feature on maxi-scooters, but its existing solution uses ultrasonic sensors more suited to dense urban traffic.)

The two companies also differ slightly on terminology. BMW refers to its Adaptive Cruise Control system as “Active Cruise Control” and calls its normal cruise control “Dynamic Cruise Control.” When I asked Ducati how they’d branded their Adaptive Cruise Control system, they murmured between themselves for a few seconds and then told me, “We call it Adaptive Cruise Control.”

How ACC works

Both systems are controlled by switchgear on the left handlebar; they can be turned on and the target speed and following distance can be adjusted while in motion. Both will accept speed selections ranging from 30 kilometers per hour (about 18 mph) to 160 kph (100 mph). Engineers at both companies emphasized that the systems were unsuited to chaotic, slow urban traffic.

When you choose a following distance, you’re actually choosing a time gap. So, the linear following distance increases with speed. BMW’s system allows you to choose from three following distances, while Ducati gives you four options.

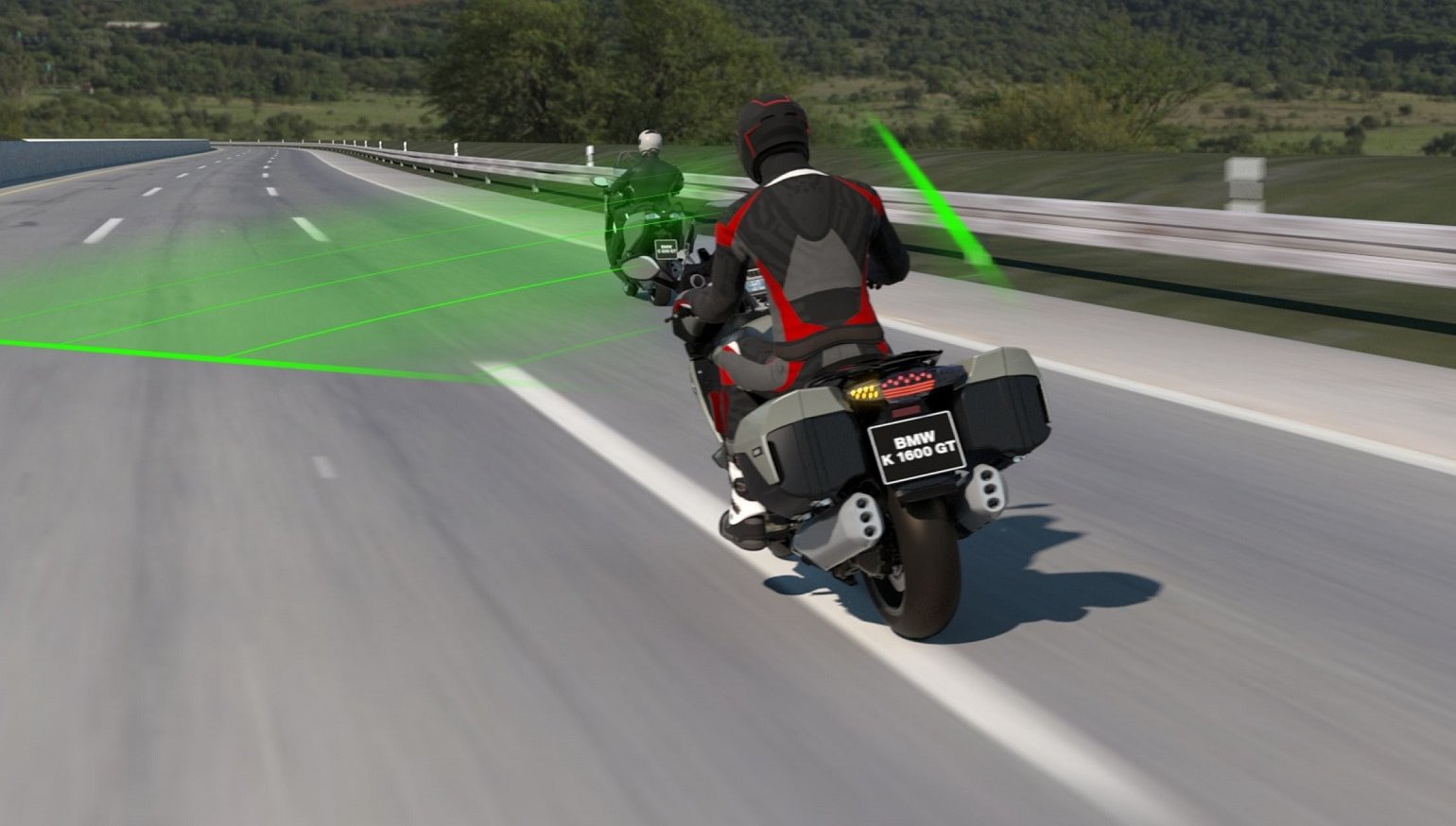

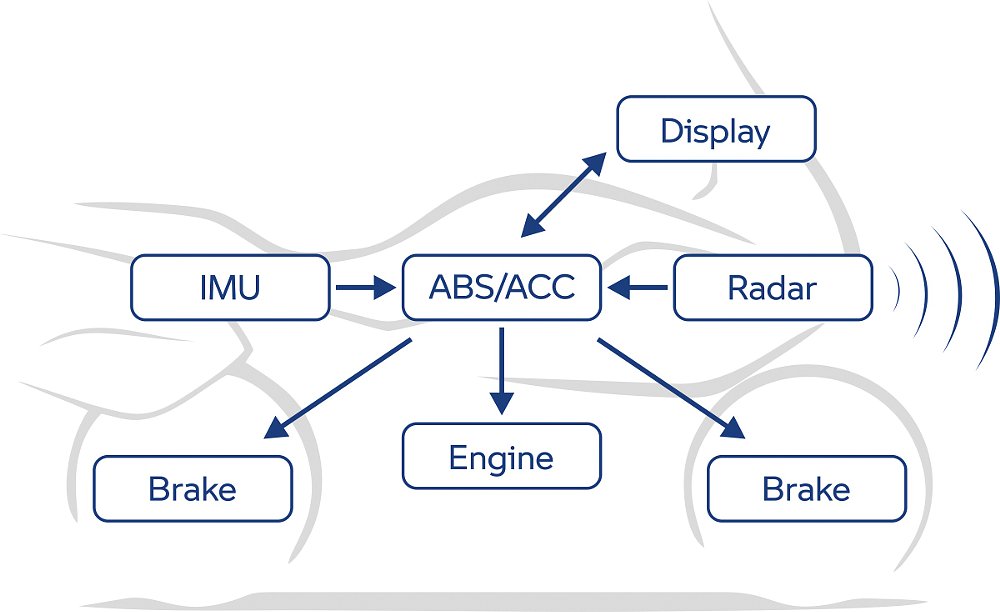

When activated, the radar sensor looks for a target vehicle to follow. Since there may be several radar reflections, an algorithm uses data from your own IMU to calculate your vector, and chooses the reflection with the vector that most closely matches yours. Think of it as Match.com for vehicles.

The radar sensor has a range of about 100 meters. A distance controller in the sensor sends an acceleration request via the CANbus to the ABS control unit. If the acceleration request is positive, the ABS unit sends a torque request to the ECU. If the request is for negative acceleration the ABS unit instructs the ECU to throttle down. If that doesn’t do the trick, it applies the brakes by itself.

Since the system will apply throttle and brakes on its own when needed, it’s perhaps unsurprising that ACC can only be activated when Traction Control and ABS are enabled. That is partially a moot point on the BMW, because ABS cannot be disabled on the R 1250 RT. Both functions can be disabled on the V4 S in the Enduro ride mode, but if either function’s disabled it’s impossible to activate the ACC.

In use, the ACC will accelerate up to the set speed to catch the next vehicle ahead of you. It will approach that vehicle until it’s following at the time gap you’ve chosen. At that point, if the vehicle ahead slows, your motorcycle will slow on its own in order to maintain the same gap.

The systems will detect and follow other motorcycles, so they’re useful on group rides, although both manufacturers told me their ACC works best if you follow directly behind the target vehicle. This could have implications if you’re used to riding in staggered formation on group rides; the ACC could interpret a clear space ahead of you as a condition warranting acceleration up to your set speed.

Both companies told me that their systems were unsuited to lane-splitting. That said, you can always accelerate by applying the throttle yourself (in Ducati’s case, the ACC system will shut off if you go any faster than about 115 mph). So you can override the ACC to squirt between cars if you want. However, the manufacturers recommend using the built-in passing function; if you signal and pull into an empty lane, the motorcycle will accelerate to the set speed or until it catches up to the vehicle ahead.

You can shift up and down with or without the clutch, although BMW recommends that people who choose the ACC option also choose Shift Assist Pro for clutchless shifting. I expect BMW’s ACC and Shift Assist Pro to be bundled together in the U.S. market.

As with automotive systems, any time the rider applies the brakes, the ACC system disengages. The systems also disengage if the clutch is pulled in and held in for about 1.5 seconds, or any time the throttle is rolled to a stop that you’ll feel a few degrees past the normal “zero throttle” position.

This vehicle brakes for algorithms

Both manufacturers have taken a lot of care to minimize the risk of riders being thrown off balance in the saddle, or even surprised when the system applies throttle or brakes. BMW’s gone even further than Ducati in this area, because it allows riders to choose between “Comfort” and “Dynamic” throttle and brake activation. (Ducati doesn’t give customers that option.)

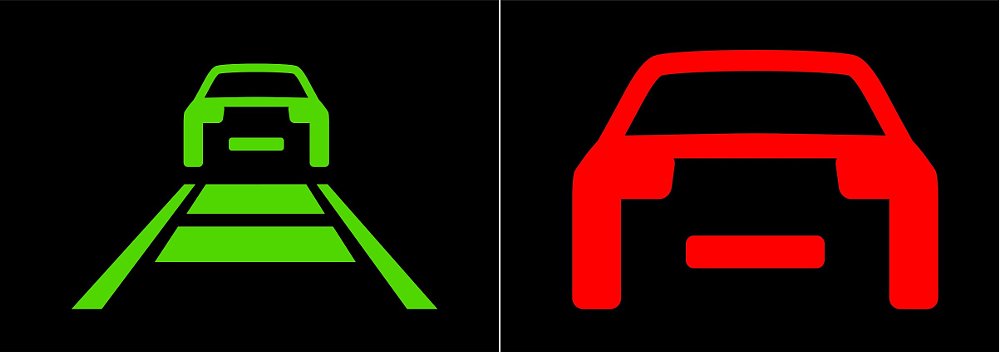

In the case of BMW, if the system even thinks that it is closing on a vehicle ahead at a rate that might require the use of brakes, a red icon resembling a car’s rear end appears on the motorcycle dash as a sort of pre-warning. Fings compares it to having a cautious passenger along. “Probably if you drive with your wife in the car beside you... [and] she sees something up ahead and suggests that you slow down, even if you’ve seen it too and realize you may not have to slow down.” (Ducati doesn’t present such a pre-warning.)

I asked Fings if BMW had tested any kind of warning sound (as some cars have) or a haptic warning before the brakes are applied. He said they had not, but was emphatic when he told me that none of the people who’ve tested the BMW system report being surprised by a braking action. I also asked whether they’d considered any kind of rider monitoring, for example making sure that the rider’s hands were on the handlebar. Answer: No.

In a followup email, Fings wrote that BMW’s algorithm ramps up braking over a period of 1.5 seconds, and that it limits deceleration to about 0.5g, roughly half of an R 1250 RT’s outright maximum braking force.

How ACC doesn’t work: Take Over Request 1

In some situations, BMW’s ACC system flashes a red warning icon on the TFT dash, instructing the rider to take over control. The first kind of takeover request (TOR1) happens if the vehicle you’re following slows to less than 18 kph (about 11 mph.) At this point, the ACC system will simply disengage. (If you’re in a high gear, you may have already had to downshift to prevent stalling anyway.)

The speed at which Ducati’s system displays a takeover request is gear-dependent. In first gear, the system functions above about 15 mph. The systems will also issue a take-over request, instructing the rider to shift to a higher gear if revs get too high.

Some cars with stop-and-go ACC and lane assist are essentially semi-autonomous vehicles in heavy traffic. That’s not how these motorcycles work at all. In BMW’s video podcast, one of the engineers who worked on their ACC system is asked about stop-and-go city traffic. He responds with a rhetorical question: Why would any motorcyclist choose to sit in stop-and-go traffic anyway, when one could just filter through it? Obviously, he’s not spent much time in the United States!

Fings told me, “You should use the ACC in situations where you would have used conventional cruise control.”

How ACC doesn’t work: TOR2

The second kind of takeover request happens if the vehicle ahead suddenly slows down, and the ACC system’s braking limit makes it impossible for the system alone to maintain the prescribed following distance. Here’s how BMW describes what happens then.

“The second warning level (TOR2) is displayed if the system detects a dangerous situation in which the distance control cannot ensure the required minimum distance even at maximum permitted brake actuation (ACC must not activate emergency braking). Any abrupt possible braking maneuver of the vehicle in front is taken into account. ACC continues to carry out any necessary braking, but the rider has to be ready to brake and if necessary must brake to avoid a collision.”

When the rider applies the brake in that “must brake” situation, the system disengages; at that moment under normal conditions, the rider should have considerably more braking force available. (The R 1250 RT comes standard with lean-angle-sensitive “Full Integral ABS Pro,” meaning that applying either brake activates both brakes.)

However, if you don’t react to a vehicle suddenly slowing down ahead of you, the ACC system will reach its peak deceleration of five meters/second2 in 1.5 seconds and maintain that braking effort, presumably right up to the moment when you rear-end the vehicle you’ve been following.

Reiner Fings agreed when I posited that the existing ACC system has most if not all of the hardware needed for a full Automatic Emergency Braking system. He admitted that Motorrad expects that capability to be available at some point. For now though, the ACC only recognizes vehicles (including other motorcycles) that are in your lane and traveling in your direction. It will not warn you or react to a car stopped in your lane.

That’s worth repeating: It will not warn you or react to a car stopped in your lane.

The big difference: Leaning

The most significant challenge in developing ACC for motorcycles was not strictly technical, but rather one of human factors. Many motorcyclists have already expressed distrust of a system that will accelerate and brake on its own, perhaps catching us off-guard. This is of special concern when leaned over.

BMW addresses those concerns by letting riders choose between two settings, “Dynamic” and “Comfort,” that change the rate at which the ACC system will open the throttle or apply the brakes. Those settings also change the system’s curve speed control.

Curve speed control works by pulling lean-angle data from the IMU. As it detects lean angle approaching a system limit, the motorcycle will slow down autonomously.

Ducati’s engineers told me that they don’t give riders a comparable choice of settings, but in all cases the rates of acceleration and braking are decreased, and the system’s peak braking force is further limited, as lean angles increase.

One moment in the BMW “Ride and Talk” video podcast that caught my interest was when Jonas Lichtenthaeler, Motorrad’s “Function Developer” for ACC, implied that one reason the system slows down in curves is that the radar tends to lose sight of the leading vehicle. The analogy that he uses is of riding at night, when your headlights illuminate the outside of a curve, not your desired path. Lichtenthaeler points out that in such a situation, if the ACC algorithm loses sight of the vehicle ahead, it might otherwise accelerate up to your preset target speed. When I asked Ducati’s engineers about cornering limitations they told me their system worked at lean angles of up to 50 degrees!

Is it for you?

Judging from comments on our earlier post about Ducati’s ACC announcement, many Common Tread readers are skeptical about this comparatively intrusive Advanced Rider Assistance System. I admit that the only time I’ve ever used conventional cruise control on motorcycles was to test systems for a review. I’ve never owned a motorcycle that had cruise control; I’ve never felt that I was missing anything by not having it. That said, I use it quite a lot in cars. On highway trips, it cuts fatigue and eliminates “speed creep.” I imagine it has saved me from a few tickets.

For some of you it’s not a value proposition, it’s the principle. You may be philosophically — or even viscerally — opposed to ceding control over a safety function. So is Adaptive Cruise Control an intrusive killjoy, or a robotic nanny that will lull you into a false sense of security? Engineers for both Ducati and BMW admitted that they themselves were skeptical — until they tried it.

Everyone who has used it told me variations of the same story, which is that ACC frees up mental bandwidth that would have been used to regulate the distance to the vehicle ahead. That improved their ability to observe traffic around them, which improved their safety. Then, they were fresher when they got to nice roads, which improved their fun.

Since I have spent the last 10-plus years living in places where the nearest good riding involved hours of boring highway transit, I think that if I was going to pop for a new R1250RT, I’d add the ACC option.

Whether we like it or not, though, ACC is going to become common. Kawasaki and KTM have both done deals to acquire the Bosch tech.

Membership

Membership