Beauty and serendipity aren’t necessarily correlated.

You may be familiar with the Golden Ratio, the Rule of Odds, or the Rule of Thirds. These concepts seek, in part, to explain what our brains find attractive when we see a thing. It should come as no surprise, then, to find that motorcycles also have a little science behind them in terms of what looks “right” to us. In this article, I am concentrating on custom bikes. In general, someone in a shed or garage making one precious keepsake has more freedom than the teams of folks dealing with budgetary, legal, and manufacturing constraints, but there are plenty of lessons to be taken from factory machines, as well.

While these aren’t hard and fast “rules” we're going over here, these are some concepts that might help you figure out how to make your own bike just so, if you're customizing, or help you understand why you like what you like, if you're just looking and admiring.

Wheels

Wheel diameter is often dictated by total motorcycle size. Metric cruisers, for example, often use 15-inch rear wheels instead of a more conventional 16-inch wheel because the bikes are often significantly smaller than a traditional heavy cruiser. In general, a larger diameter wheel will be paired with a tire having less width and sidewall height than a smaller diameter wheel, so when builders are trying to achieve a leggy look for a motorcycle, they’ll often choose a wheel that’s larger in diameter. Spoked wheels often appear visually lighter than cast wheels because observers can more easily see through them.

A little difference in size can provide an interesting look, too. A small, narrow front tire and wheel combo paired up with a wide, tall rear can help a bike sit aggressively (and is sometimes chosen for its effect on trail). It's evocative of a dragster, and can make a motorcycle look almost as though it's crouching, ready to pounce.

Custom choppers frequently use wheels of fairly different diameter because the oft-chosen springer front end can look exceptionally delicate, and pairing a tall, skinny hoop, like a 21-inch spool wheel, can help accentuate that skinniness, concentrating visual (and actual!) weight to the rear of the motorcycle. Sometimes, though, a big difference in wheel diameters isn’t pleasing to everyone’s eye, like a 23-inch wheel paired with a 16, or an 18-inch rear paired with a narrow 17-inch front. (And plenty of people don't like that "big 'n' little" pairing mentioned in the previous paragraph.) Styles have gone in and out over the years, and many customs sport tires of reasonably similar outside diameters (even if the rim size is different). There's no right or wrong answer here, but tire and wheel combos are critical to achieving certain looks. For instance, if you wanna build a flat-tracker, dual 19s are pretty much required. The farther the builder strays from that recipe, the less the end product will feel like a dirt-track bike.

Fender

Closely related to the wheels is the fender. Generally, fenders that look good follow the circumference of the tire, and the most appealing look is often to have the fender as close to the tire as practicality allows. Radiusing is an important job done on most custom motorcycle fenders, especially the rear. Unlike the front fender, the rear usually does not move with the wheel on a sprung motorcycle. Tightening a fender's radius can be performed by spreading the fender wider, which tightens the curve, or by making a series of cuts in the fender, and rejoining them after the fender is massaged into the correct arc. Conversely, narrowing the fender with pressure applied from the outside in will cause the radius to loosen.

When it comes to fender placement, a rule of thumb for rigid bikes has been to lay a drive chain over the rear tire, set the fender upon it, and then mount the fender in that location. That leaves juuuuust enough room to deal with tire growth. The length of the fender needs to be taken into account, too. Depending on how far down the back of a tire a fender comes, the fender may need to stop following the line of a tire due to the need for axle adjustability as the motorcycle’s chain wears.

On sprung motorcycles, a variety of tricks are employed to make this work. Sometimes you’ll see fenders mounted to swingarms to move with the tire, allowing much closer mounting than could usually be achieved. Often you’ll see tails chopped very short, to avoid having to have a very close match, and sometimes you’ll see straight or flat tail sections incorporated to fool viewers into seeing the fender more as a component of the bodywork than as a piece of the wheel. Many modern sport bikes utilize this to great effect by having a separate “hugger” that’s a neutral, forgettable color blend into the wheel, with a more dramatic tail section worked in as part of the body that doesn’t serve to do anything other than provide a pleasing cover for the subframe and convenient spot to mount a taillight and tag.

You may also see fenders that are aggressively “flipped” at the rear to allow a builder to use a short fender that provides an alternative arc that is aesthetically pleasing. The classic example of this is the commercially available quickbob fender that hailed from riders cutting the rear of a front springer mudguard, and mounting it onto the rear of a motorcycle, rotated far forward to provide a unique look.

Frame

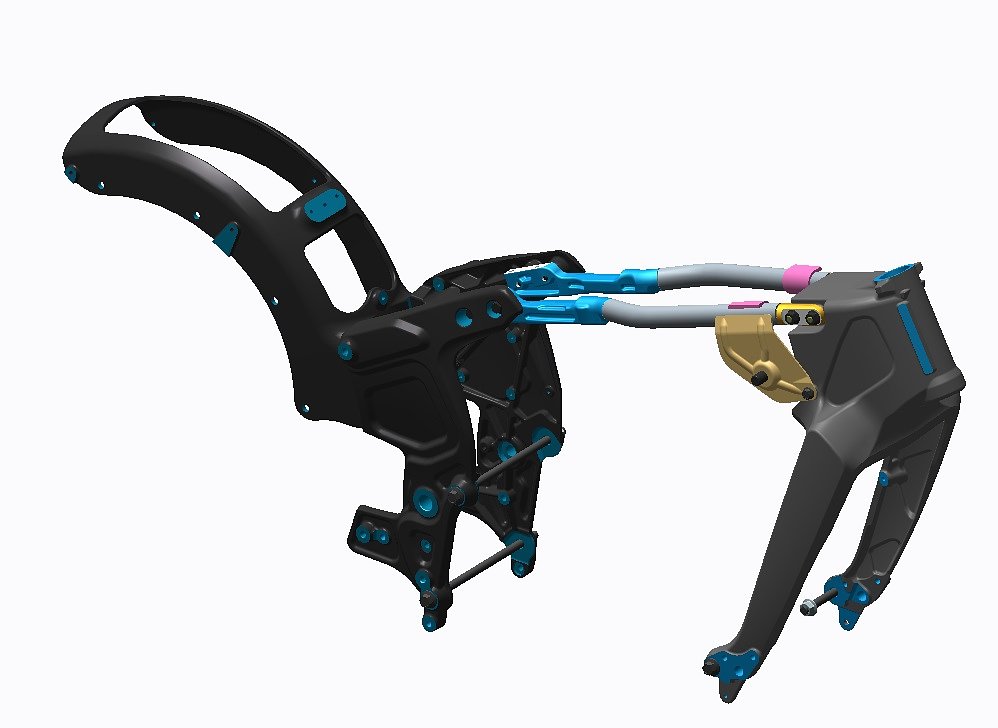

A motorcycle’s frame obviously carries the necessary components of the bike, but in some cases, it can also serve as an important visual element. In others, it’s almost completely hidden. Frames have so many different tasks, are constructed of so many different materials, and can be made of such varying shapes and sizes that it can be hard to nail down very many specific rules, but we can toss a few out there that may help you understand why you like what you like.

Frame material matters a bit here. Generally, runs of round tubing tend to look “nice” to human eyes, whereas square sections do not, unless a builder is shooting for a specific look. You can see this a lot in modern motorcycles that have square backbones: the fuel tank is usually long enough to cover that section of tubing. (A good example of this would be the Triumph America.) Smaller diameter tubing is usually of a fairly thick wall, and steel is often the material of choice.

Similarly, large, flat pieces tend to be unappealing, and those large swaths often come from voluminous aluminum: light, but made from large sections to add strength. Examine the boxed aluminum perimeter frames found on modern sport bikes: they’re often formed with graceful curves flattered by the bodywork, and contours are often formed into the metal to break up the monotony and draw the eye elsewhere. Muted colors (often black) are used to help the frame disappear a bit.

A traditional frame, made of tubing, often serves as a perimeter, or a visual border. Think of them as the lines in a child’s coloring book. (Line is another element of art.) On a rigid frame, for instance, a nice long, straight unbroken line from the headstock down to the axle is a look many riders shoot for. That line is for many a defining element of the style. Similarly, trellis frames are often seen as items of beauty, which makes sense. In addition to serving as a border for the edges of the motorcycle laterally, they also create pleasing geometric shapes (usually triangular). The trellis signifies its inherent strength, and each triangle individually inherently obeys the Rule of Odds mentioned earlier.

The frame can also define space — another element of art, including negative space. Have you ever seen a cafe racer with a big, open triangle in the frame? Many builders remove the airbox and achieve this look. Similarly, if you ever compare an older Triumph custom with a Harley-Davidson, you’ll notice far less space between the frame on the Harley than the Triumph, in most cases.

Are those negative spaces good or bad? Depends on your viewpoint. Some love the airy look of a cafe or Triumph, and others prefer the bulging appearance of the Harley. No matter your stance, the impact of the frame on space (or lack thereof) is certainly great.

The frame also imparts a sense of movement, a principle (not an element) of art. One of the best articles on custom bike design theory I ever read was a Bikeexif article penned years ago by Charlie Trelogan, an automotive designer. In it, he mentions the foundation line. On a cafe motorcycle, the subject of the article, that line is the horizontal line that’s nearly parallel with the ground, that’s usually heavily emphasized (ideally!) by the flat line of the tank's underside continuing into the flat line of the seat. Those items are borne by the frame, so making them work organically together makes good visual sense.

On a rigid bike, especially one with a shorter wheelbase, like a Triumph that’s been hardtailed, the foundational line is the line from headstock, down the spine, and onto the rear seat stays, out to the axle. Almost every custom frame tries to shoot that line as straight as possible, and on bikes that “look right,” that line, if bent or broken, will usually use the fuel tank or seat to hide the bend if possible.

In addition to serving as a visual perimeter and a foundational line upon which the rest of the bike is imagined, the frame can serve some secondary geometric purposes, as well, kind of like that trellis frame we mentioned earlier. On choppers, for instance, the angle of the seat tube influences the front fork rake and the sissy bar angle. Generally, those three lines need to complement each other because they affect that principle of movement. A bike with an extreme fork angle and a very upright sissy stick looks “off” to most eyes, and the opposite is true, too: A bike with a fairly short front end and little rake looks odd with a very “laid-back” sissy bar. Some try to match them completely, and others like some tension between the angles, but there is a relationship.

Body

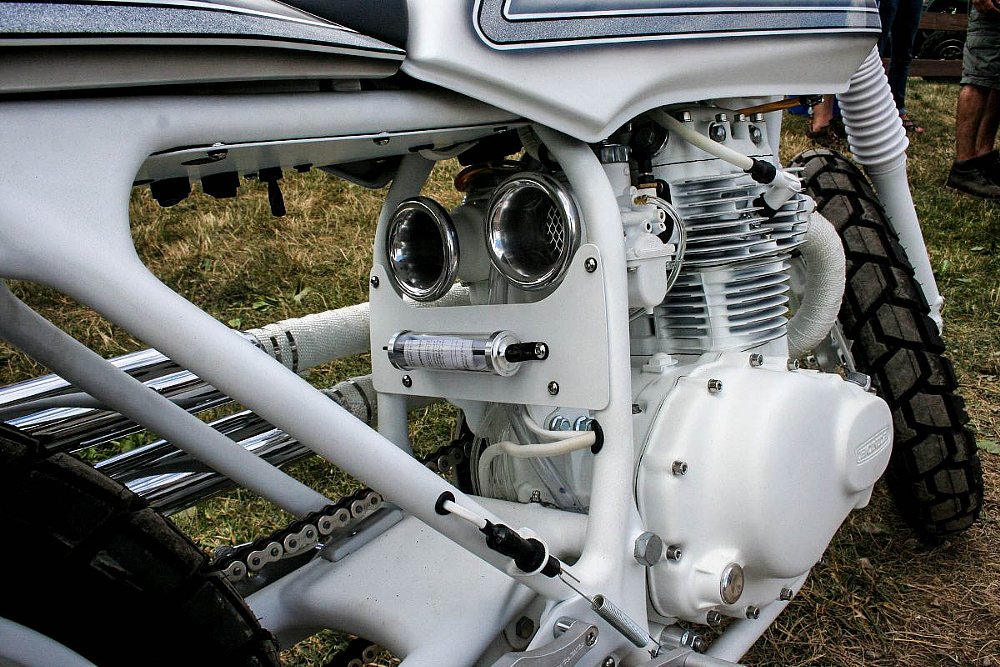

Bodywork (like fairings) originally was used on motorcycles to cheat the wind and help motorcycles slip through the air with less resistance. However, as time has gone on, the body has served also to define the shape of a motorcycle. Angularity, curvaceousness, sharp tapers, and muscularity that may or may not exist can all be suggested by well placed bodywork. Especially as motorcycles continue to be fitted with safety, performance, and emissions equipment (radiator hoses, ABS pumps and charcoal canisters pop to mind), bodywork is increasingly filling the role of “sharp-looking packaging.”

Without going too deeply into this category that could (and has) filled books, bodywork can both define and obfuscate a motorcycle. Something like a Suzuki Hayabusa or RF900 is defined by the shapes suggested by the bodywork. (I mean, all factory bodywork started as a prototype, which is in effect a custom!) But in the same breath, countless streetfighters, café racers and choppers have emerged at the hands of an owner who peeled back layers to find an item of beauty within. Or imagine, if you will, dirt bikes and dual-sports, with their sparse bodywork. A round front fender and a square headlight was once the mark of a cutting-edge motorcycle, but now is a vintage look — modern dirt machines have angular plastic residing over the front wheel, and headlights are usually shapely units that take advantage of capsule-style headlight bulbs, and the results feel futuristic when placed next to an older machine whose parts serve the same function.

Similarly, the principle of art known as proportion can really take hold with bodywork. Frames, engines, and transmissions are reasonably fixed in terms of size for most builders. However, choosing a too large dustbin fairing or a tank that’s too narrow or short can make a really neat bike look very odd. Some builders will “play” with proportion to emphasize, say, the largeness of an engine or the delicate construction of a frame, and that level of thought in mock-up usually leads to a great outcome, but ill-chosen body pieces can make motorcycles look bloated, droopy, or bulky — and it might take you a bit of examination and staring time to figure out why you feel that way.

Finishing touches

For as much time as a custom builder might spend smoothing frame welds or polishing an engine case, the reality is those pieces often get lost in the shuffle. You may never see that weld or the shiny part of that engine when the bike is assembled, but some items command a lot of your eye’s attention, even if it’s subconscious.

Finishes aren’t overlooked, per se, but few realize how much depth they can add to a motorcycle. A single finish applied to too many pieces can create a one-dimensional look. If you look at your favorite motorcycles, you’ll usually find a number of surface treatments that might look a bit schizophrenic in a pile, but once assembled into a motorcycle they create a layered look that seems more cohesive than a monochromatic theme. Paint, powder, chrome, raw metals, and even corroded and rusted parts can be combined on the exact same motorcycle to create vastly different textural “feels.”

Related to this is the concept of “themes.” Decorative metals (brass or copper, for instance), design elements (skulls or speed holes, fins and ribs) are used to create a recurring idea throughout many custom motorcycles. However, the amount and placement can really be a tightrope between “Neat!” and overdone. The accent pieces usually need to be subtle and sprinkled evenly throughout the bike. They should catch your eye in most cases — not draw it. I’m reminded of some advice I received as a younger man about aftershave. “Use enough so they know you’re there, but not so much they know you’re coming.”

Another small touch is a negative one: what you don’t see. Some things are simply distracting to the eye: cables, wiring and plumbing are frequent suspects. Bikes that look “clean” and uncluttered generally have that appearance for a reason. Internal throttles, internally wired handlebars, microswitches, and shaved fork legs all came about because builders were attempting to emphasize structural lines of the bike and minimize distractions.

And do the parts look like they know each other? We don't want parts of a bike to look like strangers. Mixing old and new parts often takes some finesse, so the bike still feels unified. Similarly, on a well weathered motorcycle, acquiring parts that have similar wear levels (or faking it!) often helps. Flame, acids, dirt, grease, and oil can all help a rookie part look like a veteran piece. I recall a custom builder I know well using cheap Wal-Mart spray paint on an outer primary, and then spending some time kicking it around his gravel drive with his children in a bizarre form of soccer — but it looked right at home once it wound up on his race machine.

We’ve just scratched the surface of what your local garage rat could be thinking when he “tosses together” another bike from parts that didn’t cost a ton, but might look really great. Generally, a well planned project with half-decent execution will look pretty killer, and now you know a little bit about what the pros think about when they’re formulating their plans. These aren’t rules, so to speak, but instead concepts that have worked well for many years. Much like poetry or music or any other creative endeavor, blowing past one or more of these rules is possible, if someone has either the skill or keen eye to do so, so don’t be surprised if you love something that’s “wrong.” That’s part of the game.

And you also know that they’re thinking about what you’ll be thinking. Perhaps you've learned a little something about why you’ll think it!

Membership

Membership