Just before Christmas, the American Motorcyclist Association sent out a press release announcing the formation of the “AMA eSports National Championship.” The new championship will be organized and promoted under a multi-year agreement between the AMA and INIT ESPORTS, a company co-founded by female motocross pioneer Stefy Bau. The release noted that the AMA may award its first esports #1 plate at the end of the 2021 season.

If you feel a slight seismic disturbance, it could be fierce and fearless AMA #1 plate holders like Bart Markel and Gary Nixon turning over in their graves.

Via e-mail, I askes AMA Chief Operating Officer James Holter what an organization with roots going back a century sees in esports.

“The phrase we keep coming back to is ‘turning gamers into riders’,” Holter replied. “While one goal is to provide a gaming outlet for existing motorcyclists, our primary goal is to connect with serious gamers outside the traditional motorcycling community.”

Simulated sports draw real fans

Whether you think the AMA should acknowledge an esports champion — as it does in disciplines like motocross, road racing, and flat track — this much is clear: esports are The Next Big Things in sports entertainment.

At a glance, esports look like video games you’ve seen and probably tried, except that players use gaming platforms to compete against one another, sometimes in a single location and sometimes at locations across the world. And spectators follow the action in real time, again sometimes in arena settings but more often at home, on Twitch or YouTube.

The 2020 World Finals of the multiplayer online battle game “League of Legends” had an “Average Minute Audience” of 23 million viewers. The Esports Earnings website tracks esports prize payouts. The site recently tallied nearly $100 million in total purses across all games worldwide. A Norwegian named Johan Sundstein, who competes as "NOtail" earned over $3 million in 2019. Almost 100 players earned more than $1 million. An American named Richard Nevins, who competes under the nom de jeu of “Ninja,” has more than 16 million followers on the Twitch gaming platform. Kent State and UC Berkeley are among the schools that now offer scholarships to esports (ahem) athletes.

The most popular esports are combat games. Some esports simulate real-world stick-and-ball sports such as basketball, but the virtual arena is one place where motorsport sticks it to the major leagues.

One reason auto racing sims are more popular than NBA2K20 is that sim rigs have become surprisingly realistic and include features like panoramic displays and force feedback on the steering wheel. Real racers now use games to familiarize themselves with new tracks and even to get a head start on suspension setups.

When the famed 24 Hours of Lemans endurance race was canceled due to the pandemic, the FIA sanctioned a 50-team virtual race. Each team was comprised of four drivers, two of whom had to be FIA-licensed racers. Although the simulated race was interrupted by two red flags (for server crashes!), professional drivers who took part were impressed by the realism and immersive nature of virtual racing.

Motorcycles ≠ automobiles

While the overlap between real and simulated car racing is significant, can you build a simulator that realistically resembles riding a motorcycle? It's not easy, largely because motorcycles, unlike cars, aren’t steered, they’re countersteered. That makes it far harder to simulate riding a motorcycle than driving a car. As far as I know, there are no gaming sim rigs that realistically simulate countersteering.

That’s not to say it would be impossible to build one. Cruden, a company based in Amsterdam, has developed a very realistic motorcycle simulator (above) with six degrees of freedom, which operates on its Panthera simulation software. A company representative told me that the base price was €336,000 but cautioned that the final price would depend on the customer’s specific configuration. Cruden’s intended customers are OEMs and institutions conducting serious R&D into motorcycle dynamics.

CKU28 Sport Fitness, a Spanish company, makes a very realistic sport-specific conditioning rig (above) for road racers. It responds to realistic rider inputs and was developed with input from former 500GP champion Alex Crivillé. It lacks only the replication of centrifugal forces pushing a rider onto the bike in corners. The company prepared a pro-forma estimate for me; a unit with pitch control (to replicate the feeling of braking and acceleration) starts around €30,000.

Still too rich? An Italian company called MotoTrainer builds a slick rider training sim rig (above) that serves as a stand for your own motorcycle. It will allow your bike to lean up to 50 degrees. Versions that simulate countersteering start north of €10,000. The MotoTrainer rig is compatible with PlayStation and PC racing games but using muscle effort to initiate turns on a MotoTrainer would put esports racers at a severe disadvantage compared to competitors using something like an Xbox controller.

A couple of years ago, a Kickstarter project called LeanGP attracted €43k in donations. In a little video clip, the LeanGP controller looks cool, but as far as I can tell, no LeanGP sim rigs have ever been delivered. Judging from the comments left on the Kickstarter page, most donors feel they’ve been ripped off.

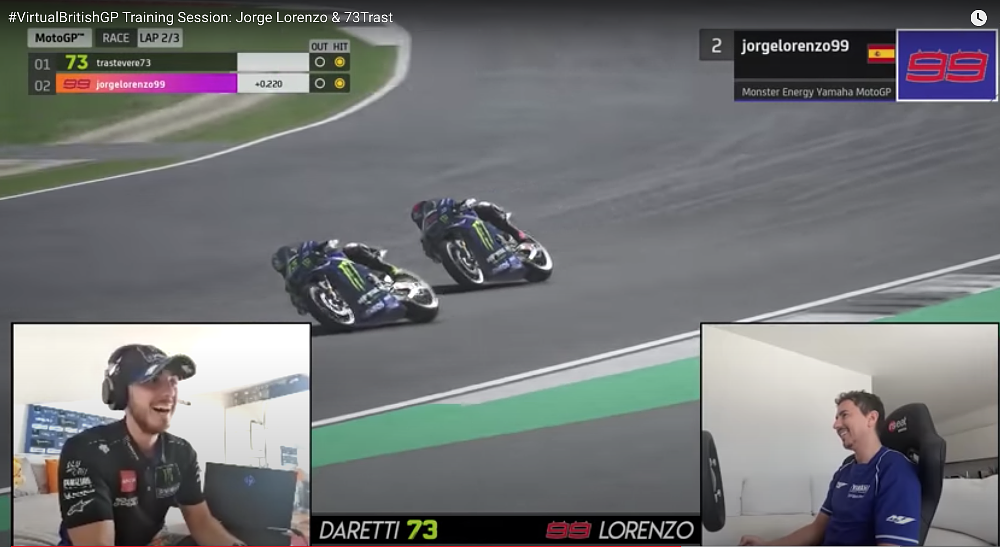

Jorge Lorenzo raced in the “Virtual British Grand Prix” during the COVID-19 shutdown. There’s an instructive YouTube video of him in a practice/coaching session with Lorenzo Daretti, an esports racing champion known in social media as @73trast.

Lorenzo is seated in his personal Thrustmaster auto sim rig, but he’s using just the seat and screen. He’s racing with a standard hand-held controller. If he’d been in a virtual automobile race, that sim rig would come close to a real driving experience. But watching him “race” a virtual motorcycle, it’s striking that he’s so physically inert.

Several tabletop “handlebar” controllers have been marketed, including the Thrustmaster Freestyler and the Yamaha MS-1, but they are no longer being manufactured. Walmart still has the Yamaha unit for sale on its website, but the product description begins with the disclaimer that the units being sold today have been sitting in the warehouse for 15 years! Some of those old rigs could be used in a “countersteer” mode, although there’s no provision for force feedback. I traded messages with serious car guy and sim racer named Steve Clark, who has built non-leaning motorcycle sim rigs that adapt old controllers for use on new gaming platforms.

"The problem with countersteering in a game is that there isn’t the gyroscopic effect like a real front wheel, so the counter steering feels weird," said Clark. "When my friends try it, they automatically try to steer the motorcycle like they would if they were driving a car.”

He also warned, “You’ll probably be faster with a regular controller than you will be with the handlebars.”

Stefy Bau’s vision

Stefy once licensed her likeness for use in an EA Sports motocross game, but she didn’t have any real interest in esports until a couple of years ago. Her epiphany came while visiting her niece in Italy in 2019.

“She was spending two or three hours a day on her iPad watching esports competitions on Twitch,” Stefy said.

She was initially skeptical, but the more she thought about motorsports’ high barriers to entry, the more she saw parallels between esports’ accessibility and her own efforts to increase diversity and inclusivity in motorcycle riding and racing.

“Suppose a kid wants to compete in AMA Supercross,” she told me, “First you have to come to the U.S., and the sport is so expensive. But a console costs only $300 and you can do esports from anywhere.”

The AMA also saw an opportunity.

“We want to expose new, untapped markets to motorcycling," Holter said. "Then, by leveraging the relationships we’ve built with those participants, we hope to communicate to them the fun, excitement and utility of riding real motorcycles.”

“Of course, a stepping stone to becoming an actual rider — or even a racer — might very well be fandom. If we can create more fans for MotoAmerica, AMA Supercross, the AMA pro motocross series, trials, off-road, land-speed — anything we sanction — that’s also a plus.”

Formula 1 auto racing has enthusiastically embraced esports and now attracts millions of live viewers for races that pit esports players against real F1 drivers. For what it’s worth, the 2018 and 2019 F1 seasons reversed several years of decline in F1’s TV audience, so esports didn’t hurt the real thing.

A handful of esports drivers have jumped into real racing cockpits and surprised race teams with skills honed on sim rigs instead of the traditional way, by starting as kids in go-karts and then climbing the rungs, with each rung 10 times as expensive.

If the AMA and INIT succeed in building an audience for motorcycle esports, the players and fans may become fans of real-life racing. I think it’s more of a stretch to convert esports fans into real-world riders or racers. The lack of a realistic and immersive sim rig might creates a bigger gulf between the esports experience of riding a motorcycle and the real-world version.

Without risk, how real can it possibly be?

Even if there were a motorcycle sim rig that matched the ergonomics and kinesthetics of a real motorcycle, an essential component would always be missing: risk.

I loved the jousting and rivalry of club racing, but that visceral pleasure was fleeting. The enduring reward I earned from motorcycle racing was a kind of self-knowledge that is hard to acquire elsewhere in the civilized world. Not that I was fearless; quite the opposite. But rather that on my best days, I was capable of achieving a Zen-like focus in spite of fear.

Without risk — and the need to conquer fear — whatever the AMA and INIT promote, it will never be a sport. Only a game.

But maybe that doesn't matter. The U.S. Army fields its own esports team under the recruiting command. Their games aren’t realistic either. Every player learns how to play by dying over and over, which is hardly a privilege shared with real soldiers. The Army hopes that connecting with esports fans will allow it to turn some of them into real soldiers, just as the AMA hopes to turn some gamers into riders.

So I’m conflicted: The curmudgeon in me certainly doesn’t think that the first AMA eSports champion will have earned a #1 plate. But I have no say in the matter, and the rest of my life will be spent in the future.

Membership

Membership